AbandonedNYC

Abandoned

Scouring the “South Pole” of New York

Rotted pilings beneath Outerbridge Crossing, with views of Perth Amboy, NJ.

From St. George, ride the Staten Island Railroad to the end of the line and you’re only a short walk from the southernmost point in New York State, at the mouth of the Arthur Kill. The name of the waterway stirs the imagination, but its Dutch origins are benign. Achter kill means back river or channel, in reference to its location at the “back” of Staten Island. Intriguingly, the route was carved out by an ancestral iteration of the Hudson River. Glacial activity altered the course to its current position, but the vestigial strait remained, isolating a sneaker-shaped land mass. Staten Island was born.

The Conference House

A stone’s throw from the so-called “south pole” of New York State, there’s an impressive bit of Revolutionary War history known as The Conference House. The name refers to a peace conference held there on September 11, 1776 between British commander Lord Howe and representatives of the Continental Congress, Benjamin Franklin and John Adams among them. Over the course of the three hour meeting, Howe urged the men to put aside their little rebellion. (They declined to do so.)

True to its contrarian nature even in revolutionary times, the borough was a loyalist stronghold, warmly greeting British troops upon their arrival. Hundreds of islanders enlisted in the British army as the conflict escalated. George Washington himself called the Staten Islanders “our most inveterate enemies.” John Adams was less generous, labeling them “an ignorant, cowardly pack of scoundrels, whose numbers are small, and their spirit less.”

Low tide in the Arthur Kill reveals the remains of wooden ships.

The borough is home to several lesser-known “boat graveyards” in addition to the famous Rossville salvage yard.

Tracing the Arthur Kill past the quaint historic houses of Tottenville, we enter into wilder territory and arrive at the base of Outerbridge Crossing, which spans the Arthur Kill between Charleston, SI and Perth Amboy, NJ. New Yorkers could be forgiven for assuming the name refers to its status as the most remote bridge in New York City, but it’s actually named for Eugenius Harvey Outerbridge, the first chairman of the Port Authority of New York and a resident of the borough. “Outerbridge Bridge” wouldn’t do, so they deemed it a “Crossing.”

Wandering these regions can be treacherous if you don’t plan ahead. As the tide ebbs and flows, open shoreline gives way to mud and water, leaving you with no way out but the head-high reeds of the marsh. In nesting season, geese are liable to attack (speaking from experience here). But for those willing to brave the wilderness, there are rewards. The fabric of the city dissolves on the outermost edges of Staten Island, and the ground is a layer cake of archaeological finds.

The remains of the Atlantic Terra Cotta Company factory line the shores of the Arthur Kill at the end of Ellis Street.

One area of interest at the foot of Ellis Street marks the site of The Atlantic Terra Cotta Company, which made colorful architectural ornaments for many notable city buildings, including the Flatiron and the Woolworth. It closed down in the 1940s and was demolished soon after, but much of the old factory is still there in the form of rubble. Enterprising beachcombers can still find Atlantic Terra Cotta tiles if they hunt long enough. (The old adage “leave no stone unturned” applies here, as many of the most intricate pieces are one-sided.) I managed to find a beautiful acorn-themed tile with an ATLANTIC stamp, but plain bricks were more readily available.

Many of them are inscribed with the names of long-gone manufacturers, resembling fragments of time-worn tombstones. Thanks to these markings and a devoted online community of brick collectors, it’s a simple matter to pinpoint their origins. The “RICHMOND” and “ATLANTIC” bricks were made in Staten Island, but others trace their ancestry to Brooklyn or New Jersey. Some are from much farther afield—“RELIANCE” Bricks hail from Texas; “MO REX” from a town called Mexico, Missouri. How all of them ended up here is a bit of a masonry mystery.

Manufacturer’s marks on the bricks point to a wide range of origins.

Just inland, marshes give way to roving woodlands that hold secrets of their own. If you look into any patch of untended forest, and many of the front yards, you’ll find a wealth of rusty relics of the one man’s treasure variety. While there isn’t much history to glean from them, they are fascinating to look at. A natural area known as Sharrot’s Shoreline was once filled with mountains of scrap metal and scores of abandoned cars. Only a few remain today after cleanup efforts by the city. What’s left is a serene nature reserve that would thrill most bird-watchers, though they might have a hard time finding a way in.

Nearby, a deserted graveyard of auto parts marked one of my most surprising finds to date. Chief among the relics was a group of corroded buses, apparently from the 1960’s. While the scene has an ancient air, the plot was the site of a multi-generational family business until quite recently, according to a neighbor who gave me a stern warning for trespassing on private property. (For that reason, I wouldn’t advise seeking them out for yourself.)

This has been the second installment of a series of posts on the edges of Staten Island. Next up, we’ll continue our trip down Arthur Kill Road, delving deeper into the history of Charleston and the “haunted” Kreischer Mansion. See more photos from the project here.

A foot of snow covers a “graveyard” of auto parts…

..pictured here in the fall.

Approaching the “Forgotten Borough”

Seagulls follow in the wake of the Staten Island Ferry.

Hello friends, its been a while. I’ve been on a bit of a hiatus from poking around abandoned buildings, but I’m back now with something a little different. This is the first installment of a series on Staten Island—an area of the city that tends to go unnoticed, but is very much worth exploring.

For the unfamiliar, Staten Island stands with Manhattan, Brooklyn, the Bronx, and Queens as one of the five boroughs that make up the city of New York. It is the third largest and least populated of the five. Its identity has always been somewhat distinct from the city at large, due in part to its geographical isolation. Prior to the construction of the Verrazano Bridge in 1964, no crossing existed between Staten Island and any other borough. It remains something of an outlier today, with a suburban nature and right-leaning political tilt. A record of neglect from city government has earned it the oft-repeated title “the forgotten borough,” and the name has stuck.

The Staten Island Ferry departs from Lower Manhattan.

From a Manhattan-centric point of view, a trip to Staten Island begins with a ride on the Staten Island Ferry. Over 21 million passengers embark on the 25-minute journey from Lower Manhattan to St. George each year. With dramatic views of the Statue of Liberty and the surrounding harbor, it’s a well-known attraction for New York City tourists. The ride is offered free of charge by the city’s Department of Transportation, but that hasn’t always been the case.

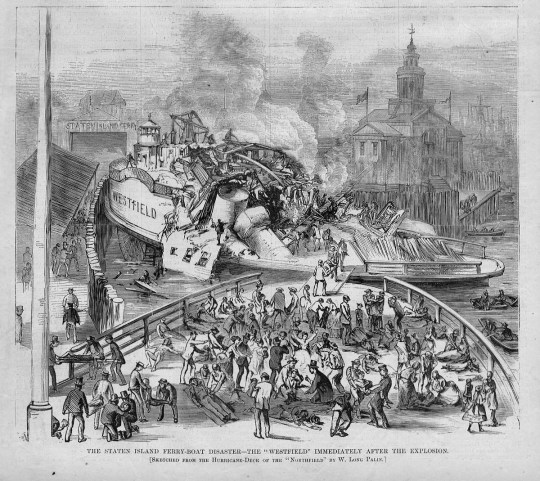

An engraving of the 1871 “Westfield” disaster.

Back in the 18th century, sailboats manned by private individuals competed for fares between Manhattan and Staten Island. In 1817, the first mechanically powered ferry service went into operation, under the direction of Captain John de Forest of the Richmond Turnpike Company. His brother-in-law Cornelius Vanderbilt took over in 1838. Existing ferry service proved inadequate as Staten Island developed, and accidents were common.

In 1871, a boiler explosion on one of the ferries claimed the lives of more than 85 passengers. Jacob Vanderbilt, the president of the Staten Island Railway at the time, was charged with murder, but never convicted. In 1901, a ferry operated by the Staten Island Rapid Transit Company collided with a Jersey Central ferry and sank into the harbor soon after departing the port at Whitehall. Though the disaster was far less deadly than the 1871 episode, city authorities used it as justification to seize control of the service by 1905.

The iconic orange color of the ferries was adopted in 1926, to increase their visibility in heavy fog and snow.

Leaving Manhattan.

A nickel fare was the rule through most of the 20th century, but was increased in 1975 to a quarter, and in 1990 to 50 cents, causing an uproar among borough residents. Coupled with mounting grievances over the Fresh Kills Landfill on the island’s west shore, the fare hike gave rise to a secession movement, which culminated in the passage of a non-binding referendum to make Staten Island an independent city in 1993.

Efforts to secede were subdued by the election of Mayor Rudy Guiliani, who rode to power due in part to overwhelming support from Staten Island voters, many of whom had been won over by his promises to close the landfill and do away with the fare. He followed through on both, abolishing the fare in 1997 and closing the landfill in 2001.

The Verrazano Bridge was the longest suspension bridge in the world at the time it was built.

While the ferry has played a significant role in the history of Staten Island, the construction of the Verrazano-Narrows Bridge has arguably had the greatest impact on its development. The story of Staten Island can generally be understood in terms of two epochs—before and after November 21, 1964, the day the bridge first opened to traffic.

Long-time residents speak longingly of Staten Island before the bridge—when country roads meandered through sweeping forests, quiet beach communities, and open expanses of farmland crawling with nanny goats. In the 19th century, full-time islanders lived side by side with some of the city’s wealthiest residents. As the industrialized city minted new millionaires, many of them looked to the rolling green hills of Staten Island as a scenic escape.

The nature of the borough was permanently altered as the Verrazano-Narrows Bridge prompted a mass migration of newcomers from overpopulated Brooklyn. The influx covered farms and forests with mile upon mile of tract housing, plaguing the island with traffic problems that persist to this day.

The official name of the Verrazano-Narrows Bridge includes a misspelling of its namesake, Florentine explorer Giovanni da Verrazzano.

As much as the borough has transformed over the years, it has retained its essential otherness. Crossing the harbor by ferry or bridge signals a psychological detachment from the urban environment of New York as we know it. In the hum of traffic, or the roar of surf, the city melts away and you enter a new frontier. Beyond and in-between the strip malls and cookie-cutter houses, scattered remnants of an older, more pastoral Staten Island await. There, Times Square feels a million miles away.

Over a series of upcoming posts, I’ll be examining the many artifacts and oddities that litter the far-flung edges of the borough, and sharing the history behind them. In the meantime, you can visit my website to see more photos from the project, “Arthur Kill Road.”

View of Staten Island obscured by fog, from Bay Ridge, Brooklyn.

An early morning at Fort Wadsworth, on the opposite side of the span.

Navigating the Sailor’s Infirmary

The Sailor’s Infirmary

In 1831, “An Act to Provide for Sick and Disabled Seamen” was passed by the New York State Legislature. A tract of farmland was acquired for the purpose, and by 1837, a proper hospital was constructed, funded by a head-tax imposed on sailors entering the Port of New York. The intention was admirable and the structure was impressive. Looking at the distinctively 19th-century facade of the old Sailor’s Infirmary today, it’s easy to imagine the place brimming with leathery old salts in their twilight years, regaling each other with adventures at sea that’d put Herman Melville to shame.

In those days, the porticos of the Infirmary offered commanding views of the New York Harbor and the surrounding countryside. In 1862, the Infirmary’s Chief Physician rhapsodized on the subject: “the weary invalid can breathe the bracing air of the sea…the sight of his chosen element, covered with the white winged messengers of a world-wide commerce that fills his mind with hope and cheer.”

Today, its pastoral surroundings have been swallowed up by development, the “white-winged messengers” have vanished from the harbor, and the halls of the hospital no longer resound with tales of youthful exploits in the exotic port cities of the world. Instead, a fire alarm near the front door blares interminably, to nobody at all.

The hospital as it appeared in 1887.

Expansive porches provided views of the harbor to ailing seamen.

While the idea of a hospital for sailors might seem odd to the modern observer, there was an urgent need for this sort of specialized care in the 19th century, when sailing was a much more common occupation and working conditions were deplorable. The Infirmary’s first Chief Physician described the health of a newly admitted patient in 1838 as such: “Arrived last night on brig from round Cape Horn…Has been to sea 118 days and had nothing but indifferent salt food to feed upon…Twenty days after sailing his gums became sore and spongy and bled very freely…Around the small of each leg caked hard and over the instep a deep blue almost black color…Suffered universal pain…Very much prostrated and emaciated and was brought into the (Infirmary)…Had no lime juice on board nor any other antiscorbutic effectual in preventing scurvy…It is in this shameful manner vessels are provided to the destruction of seamen…An object of pity to behold.”

In addition to advocating for better living and working conditions for seamen, the Sailor’s Infirmary made a lasting impact on world health as the birthplace of one of the most formidable biomedical research facilities in the world. In 1887, a young doctor founded a one-room bacteriological laboratory in the attic of the hospital to investigate epidemics like cholera and yellow fever. Over the course of the 20th century, his humble “Laboratory of Hygiene” evolved into a federally-funded research initiative that still operates today with an annual budget of $30 billion. Needless to say, it outgrew the attic long ago.

Researchers at work in the attic’s “Laboratory of Hygiene” (1887)

The attic as it appears today. The area was renovated in 1912.

Over the course of the 20th century the infirmary greatly expanded its services, and the campus grew to include a seven-story hospital and multiple ancillary buildings, dwarfing the original structure in the process. Under federal ownership, the grounds served military families, veterans, and later the general public. An organization of the Catholic medical system took over in 1981, and the hospital’s focus pivoted to psychiatric care and addiction rehabilitation. In recent years, the campus has been racked with financial problems, and its services have been consolidated to a few floors of the main hospital building. The rest of the complex sits abandoned, facing an uncertain future despite multiple landmark designations.

Like many grand, old buildings, the 1837 Infirmary appears to have been shut down from the top down. Dental clinics and early childhood programs lingered into the early 2000s on the lower floors, while the top floor sat unused for decades. Today, the interior is largely empty and plain—drop ceilings and fluorescent lights abound. But the attic retains a much older patina, and a few odd relics that feel fantastically out of step with the modern trappings below.

(Note: This is one of those rare abandoned buildings that isn’t vandalized beyond all recognition. In the hopes of keeping it that way I’ve chosen not to disclose its actual name and location, or to identify some key elements of its history.)

Teddy bear wallpaper and faux stained glass in an area used as a preschool.

Old hand painted lettering exposed under layers of chipped paint.

I’m not sure what the artist was going for here. Abstract rendering of a barn?

A bit of ornamentation was still visible on the stairs.

Upstairs in the attic, a fascinating pedal-operated sewing machine.

Mouldering files in the south wing.

Solid wood wardrobes were far older than furniture on the lower floors.

A red door led into a utility room.

Storage spaces in the attic held a number of intriguing artifacts.

Including a set of 1940s dental chairs.

In other news… I’ve got a new website that just went live. Head over to www.willellisphoto.com for a look at some of my other photo projects, plus a sampling of the work I do for a living (shooting non-abandoned architecture and interiors.) You can also sign up for my newsletter if you’re so inclined, or buy a book. (They’re 10% OFF with the code “ANYC.”)

Port Reading’s McMyler Coal Dumper

The abandoned McMyler Coal Dumper in Port Reading, NJ

There’s a stretch of the Arthur Kill between Rossville, Staten Island and Port Reading, New Jersey that’s something of an abandoned wonderland. From the New Jersey side, the horizon is dominated by the twin natural gas tanks of Chemical Lane, and the famous Staten Island Boat Graveyard is plainly visible just across the water. But towering over the scene is a structure that rivals both with its staggering beauty and power—the McMyler Coal Dumper.

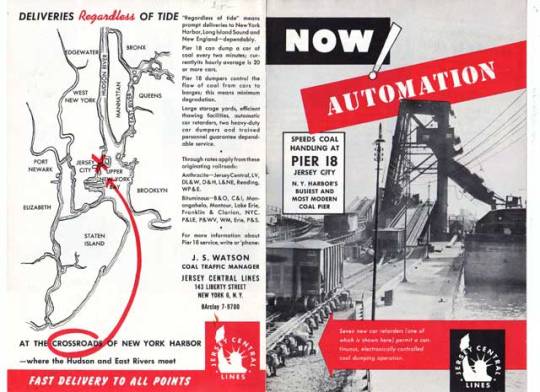

Actually, it would be more accurate to call it a McMyler Coal Dumper. It was one of many nearly identical structures built on the shores of the New York Harbor in the early-to-mid 20th century, including two on Pier 18 in Jersey City. But the Port Reading site is notable for being the last one standing in the New York area. It was constructed in 1917, making it 99 years old at the time of this post.

A 1957 ad for Pier 18 in Jersey City, which boasted two “Big Mac” McMyler Dumpers.

In a vast regional network of coal mines, breakers, railroads, and manufacturing hubs, these machines provided a vital link that helped fuel New York’s industrial age, transferring massive amounts of coal brought by rail from Pennsylvania and the Alleghenies into ships entering the harbor. A McMyler Dumper could unload a 72-ton car of coal every two and a half minutes, operating on a continuous loop for maximum efficiency.

Upon entering the pier, railroad “hoppers” carrying a full load of coal would be pushed up a ramp with a mechanism called a barney. Once in position at the base of the tower, the entire car and its contents would be lifted up on an unloading platform and tilted at 120 degrees, spilling the coal into an enormous “pan,” which funneled the material through an unloader chute and into the holds of outgoing barges. Once empty, the car would be lowered and pushed onto a kickback trestle by the next car in the line-up. These rails looked very much like a roller coaster, and they worked in a similar fashion, using the power of gravity to propel empty cars off of the pier and into the rail yards beyond. The contraption required twelve men to operate, and the work was risky. The brute force of the machine claimed many lives and limbs over the years.

A braver soul would have climbed the tower, but I was satisfied with the view from the pier.

The design stood the test of time, and the pier operated for over 60 years with nearly uninterrupted use (a fire caused considerable damage in 1951, but the unloader was quickly rebuilt.) With demand for coal declining, the machine dumped its last load in the early 80s, and has been steadily deteriorating ever since. Though there has been interest in designating the structure an historic site, its location on private property in an active industrial area has made it an unlikely candidate, and the cost of restoring or moving the structure would be prohibitive, to put it mildly. Unless new industrial development threatens the site, it will likely remain a picturesque ruin for another century before eventually collapsing into the Kill and vanishing into the muck.

That is lucky for the throng of Canada Geese who’ve made a surreal home out of the hulking relic. Though they’re nice to look at, I’ve never had a pleasant encounter with these creatures, and have been charged at by enough of them on the remote shores of the outer boroughs to know they mean business. This time around they were content to squawk and hiss their disapproval from a distance, but I would advise everyone to stay far away during nesting season, which is right around the corner.

The self-appointed guardians of the coal dumper.

A pair of steam engines inside the machine room powered a cable drum…

…which controlled the “barney,” a mechanism used to push cars onto the unloading platform.

These cable drums raised and lowered the unloading platform. Much of the machinery has been removed by scrappers over the years.

The place has a fair amount of graffiti, some quite old. Kaleen’s protestation on the upper right was particularly endearing.

A derelict ferry boat sinks into the Kill on an adjacent pier.

The pan and chute, pictured here, were left in an upright position until Hurricane Irene sent them crashing onto the pier below in 2011. An operator would have sat in the little chamber on the right. A pair of abandoned gas tanks in Rossville, Staten Island can be seen on the horizon.

Low Tide at the McMyler Coal Dumper.

You can see (a model of) a McMyler Coal Dumper in action in the following video:

Time Traveling in the Children’s Ward: Rockland Psychiatric Center

Pink walls distinguish the girl’s ward of the former Rockland State Hospital children’s building.

Old buildings have many lives. Often the objects left behind in a modern ruin only reflect a place’s most recent iteration. But in Rockland County, one structure exists as a veritable nesting doll of time periods. Today, some areas of the abandoned Children’s Hospital at Rockland Psychiatric Center are unsettlingly modern, looking like a tornado swept through a present-day kindergarten classroom. But stepping from one room to the next can take you back another 10, 20, 30 years…

A coffee mug seems out of place in this heavily decayed section of the hospital.

The squat, maze-like ward was constructed in 1929 to house the youngest subset of Rockland State Hospital’s population. (The history of the institution and its notable bowling alley were outlined in a previous post.) Though it hasn’t been used to house mentally ill children since the 1960s and 70s, it continued to serve the needs of kids and families in recent decades. Beginning in the 1980s it was used as a day care center for children of RPC employees called “Kid’s Corner.” In 1998, sections of the building were used for a program called “Under the Weather,” which provided free care to moderately sick kids, enabling their parents to get back to work while their children recuperated. These valuable programs were abruptly closed by the Department of Mental Health in 2008 for budgetary reasons.

This section of the building was last used in the early 2000s as a day care center.

A Peanuts mural from the 90s or early 00s would have been in poor taste several decades earlier.

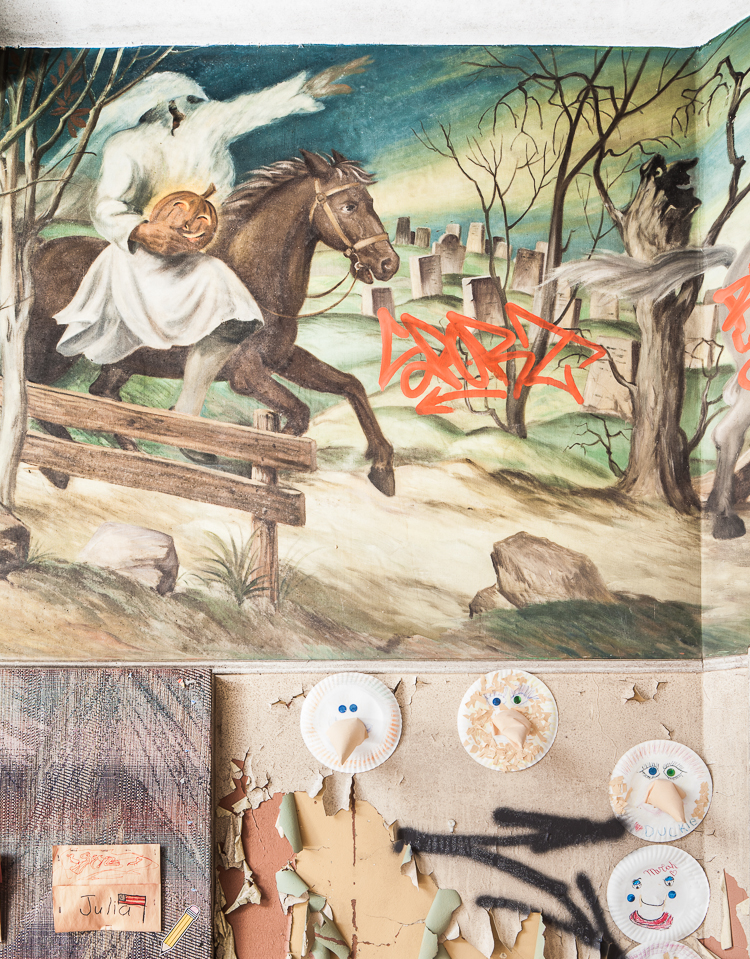

All of these developments can be traced through the hospital’s extensive collection of murals. They vary greatly in quality and subject matter, but all represent a concerted effort by founders and staff to brighten up the institutional halls over the years. The finest of them is a series of thoughtfully designed and obviously professional works depicting scenes from the tales of Washington Irving. These and a similar set depicting the four seasons were painted in the 1940s by the Works Progress Administration muralist Victor Pedrotti Trent. Much of the work is well-preserved, but some areas have suffered irreparable water damage. Years ago a study estimated that moving and restoring the paintings would cost $100,000, a prohibitive figure. Since then, there’s been little interest in preserving them.

In one section of the mural depicting classic stories by Washington Irving, Rip Van Winkle awakes from a long slumber.

Ichabod Crane flees from the Headless Horseman in this scene from “Sleepy Hollow.” Note the creepy face in the hollowed out tree.

Some sections of the mural are heavily damaged by water and temperature fluctuations.

Through the painted vestibule, beer bottle middens pile up in a relatively plain auditorium.

The building is the oldest of several structures on the campus that catered to children with psychiatric disorders. A modern children’s center is still in operation at Rockland Psych, and another built in the 1960s is currently being leased as a filming location for the hit Netflix show “Orange is the New Black,” standing in for the women’s prison depicted in the series. The 1929 hospital was slated for demolition years ago, but that doesn’t appear to be happening any time soon.

Though much of the building is crowded with modern-day kid stuff, some wings of the structure–namely the former boy’s ward–appear to have been walled off during the 80s and 90s. Those halls are largely empty, and the few artifacts left behind are far older and institutional in nature. I wonder if the youngsters at Kid’s Corner realized there was a children’s asylum ward preserved like a mosquito in amber just on the other side of their playroom…

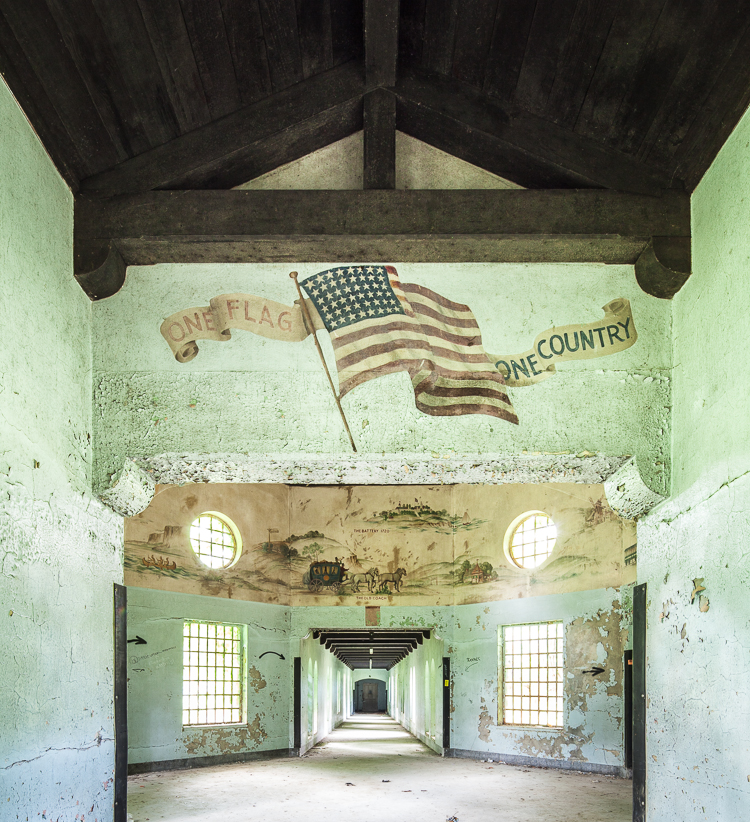

A mural with patriotic themes characterizes the boy’s wing of the structure.

Though not as impressive as the Trent murals, it offers a charming timeline of the development of New York City…

…beginning with the voyage of The Half Moon, a Dutch East India Company vessel.

A few relics from the state hospital era lie scattered around the halls, likely moved here for an urbex photo op.

Paper stars wither like autumn leaves over a doorway in the former boy’s ward.

IN OTHER NEWS… I’ve had a few spots open up on a tour of Dead Horse Bay I’ll be leading this weekend. It will take place Sunday, November 8th and we’ll be meeting at 10AM. It’s short notice, but I’d be happy to have a few more folks join in! Tickets available at this link.

ALSO… I’m excited to announce Abandoned NYC just went into its second printing! Thanks to all who helped me reach this milestone by ordering a book, showing up to events, and supporting the blog. To those who haven’t gotten their hands on a copy, get your signed first edition while supplies last!

Inside Rockland Psychiatric Center

An abandoned section of the former Rockland State Hospital, now known as Rockland Psychiatric Center.

In 1923, the New York state legislature passed a $50 million bond issue for the construction of new mental hospitals. After a disastrous fire at Ward’s Island in 1924, “where scores of mentally afflicted…were burned to death,” $11 million was set aside for a new campus designed specifically to relieve overcrowding at institutions in New York City. The town of Orangeburg, NY was chosen for its proximity to the five boroughs, picturesque surroundings, and “salubrious climate.”

The hospital once housed 9,000 people, including patients and staff.

With funding in place, the construction of the Rockland State Hospital for the Insane moved forward at a staggering pace. Townspeople looked on as the monstrous institution swallowed up tract after tract of farms, houses, and undeveloped land. As patients flooded into the new buildings by the thousands, escapes became a regular occurrence. The “potential menace” of this “new and formidable population of undesirable outsiders” was a cause of great concern for locals. Infrequent but grisly murders in the vicinity of the hospital were attributed to “mentally disturbed” escapees. But the real horrors were occurring on the inside, as many of Orangeburg’s citizens could personally attest to–the institution was one of the largest job providers in the county.

Chipped plaster, masonry, paint, and wallpaper fill a water basin.

The real trouble started during World War II, when lucrative war industry jobs lured much of the staff away and a large number of Rockland’s male attendants left to join the armed forces. As the population soared to nearly 9,000, patient-to-staff ratios plummeted. “The work is hard, disagreeable and frequently dangerous, and the hospital has found it next to impossible to recruit employees.” New hires during this period were often untrained and unqualified. From a 1940s Times article: “An employment bureau in New York City sent a number of applicants here, but most of them were found to be suffering from arthritis, cardiac ailments or “unnatural” temperament and had to be sent home. ‘Some of them should be patients,’ Dr. Blaisdell said.”

A stash of nudie magazines hidden long ago in the basement of a kitchen area.

Like most all institutions operating during this period, the overcrowding and lack of effective treatment led to systemic abuse and negligence. Until the development of antipsychotic drugs in the 1960s, shock therapy and lobotomy were the only treatment methods available for severe cases of schizophrenia and other mental illnesses. As the century progressed and the new drugs became readily available, most patients were able to live independently outside of the asylum system. Since the 1970s, Rockland Psychiatric Center (as it is now known) has predominantly been used as an outpatient facility. By 1999 it housed less than 600 patients. Several new facilities were constructed in more recent years for outpatient care, but vast expanses of the 600 acre campus are entirely empty.

Mattresses piled up in a dayroom.

Today, a grid of overgrown streets divides a vast configuration of maze-like buildings known only by number. These were separate wards for men, women, children, and other subsets of the population like the infirm, the violent, and the criminally insane. Others were workshops, auditoriums, power plants, administration buildings, staff housing… the list goes on and on.

Exploring the buildings can be confusing and perilous. One ward’s heavy wooden doors had the nasty habit of slamming shut and refusing to open again, which can be a serious situation when there’s only one or two ways out. My solution was a series of improvised doorstops–beer cans, scraps of debris, whatever I could get my hands on–which doubled as a trail of breadcrumbs to give me a reasonable hope of finding my way out again.

One of Rockland’s most interesting features is the old four lane bowling alley. It’s a heavily trafficked area full of tempting props. Pins, balls, shoes, and trophies have been endlessly moved around, manipulated, and arranged into perfect triangles in the middle of the lanes. While I don’t blame fellow photographers for this sort of thing, it can be disappointing to walk into something that looks more like a stage set than a wild, unpredictable ruin. I’ll take that over the mindless graffiti–some if which I removed with a little Photoshop magic in the images below.

Despite all the modern mischief making, the bowling alley represents the best intentions of the institution to provide quality of life to patients who spent their lives at Rockland. These lanes must have been a welcome distraction from the monotony of asylum living.

Stay tuned for an upcoming post on the Rockland Children’s Hospital, which features an impressive collection of WPA murals.

A well-preserved bowling alley was located on the ground floor of a recreation building.

Blank score sheets could be found behind the ball return.

The AMF bowling equipment may date back to the 60s or 70s.

Bowling balls pile up at the end of the lanes from previous visitors.

Compared to the bowling balls, the pins were scarce. Many had been stolen over the years.

Wood shelving used for bowling shoes, once arranged by size.

Trophies for male and female bowlers.

A Wintry Return to the St. Nicholas Coal Breaker

The St. Nicholas Coal Breaker, mid-demolition

The Pennsylvania coal region was once dominated by 300 breakers–mammoth factories that crushed and cleaned raw coal into the consumable commodity that fueled the Industrial Revolution. Today, a few modern plants meet the drastically reduced demand for the stuff. Of the old glory days when coal was king, only St. Nicholas remains.

The structure once held the distinction of being the largest coal breaker in the world, and its sheer size must have played a part in staving off the wrecking ball for the last 50 years. But according to the president of Reading Anthracite, the building’s owner, the place has become an “eyesore and a liability,” and its total demolition is imminent. A state-funded study to determine the cost of transforming the ruins into a historical attraction came up with a figure in the tens of millions.

With exterior walls removed, skeletal views of the plant’s interior come to light.

The demolition won’t happen in one cataclysmic, cathartic crash. Rather, the breaker is being dismantled piece by piece, and mined for valuable scrap metal along the way. The process is expected to last into next year, having been underway since Fall 2014. With a bit more of it gone every day, visitation has picked up as folks have poured into the region for one last look. Security positioned outside aim to ensure they respect the No Trespassing signs.

I took my “one last look” in February on a day that was way too cold to spend in an abandoned factory. Much of the metal siding had already been removed, opening up dollhouse views of the interior. Inside, light poured into corners that had been pitch black before. Elsewhere, panoramas of the surrounding landscape spread wall to wall and floor to ceiling.

After 50 years of abandonment, the old St. Nicholas Coal Breaker still inspires awe and commands respect. The interior of the breaker is noticeably free of graffiti. Visitors have stuck to more temporary means of commemorating their presence, tracing initials in the grime of a dusty control panel or chalking them up on a blackboard, avoiding outright acts of vandalism out of reverence for the building. It’s impressive not only for its physical size and beauty of design, but for the time and place in American history that it represents, a coal industry that employed 180,000 workers and enabled a young country to rise to the forefront of the industrialized nations. As St. Nick falls, little remains to tether that heritage to the here and now.

Otherworldly views of the frozen coal fields outside the breaker.

Coal dust mingles with snow drifts where the structure is open to the elements.

Names scrawled in a dusty control panel.

A control room in the upper reaches of the breaker.

Empty shelves in a maintenance room.

Enormous wooden molds for replacement parts littered this floor.

Construction vehicles stalled in the snow, seen through an upper floor of the breaker.

The conveyor, where raw coal began its journey through the breaker’s machinery.

Machinery salvaged from the breaker prior to demolition.

For more history on the St. Nicholas Coal Breaker, see the original post:

Doing Time in the Old Essex County Jail

The Old Essex County Jail (Prints Available)

Many of the most remarkable abandoned buildings loom over their surroundings and dominate the landscape, but Newark’s Old Essex County Jail is barely there. Much of the structure is walled off behind a twelve foot barrier, and all that rises above it is difficult to discern through the overgrowth. On the grounds, the building remains obfuscated, half in ruins and only visible in parts, with an absence of any unifying architectural feature. Inside, its footprint is no less disorienting, resulting from a series of haphazard additions made at the turn of the 20th century as the jail’s population increased. Unlike the comforting symmetry of asylum wards, the whole disordered mass seems to be governed by a bizarre dream logic, made all the more sinister by the fact that you can’t look the building in the face.

Doorway to the office wing

The jail is known as a haven for “crackheads,” and it’s absolutely filled with garbage and drug paraphernalia, some old, some new. When I first visited a couple of years ago, we had only been inside for a few minutes when the place started coming to life around us, first clanks and creaks, then voices and shadowy figures walking by in the hallways. It wasn’t my decision to leave that day before we came face to face with anyone, but I didn’t put up much of a fight. As sympathetic as I felt toward these unfortunates, I figured that anyone voluntarily residing in an abandoned prison cell was in a desperate situation with very little to lose.

In some areas, bars had been removed by scrappers.

A shaft between prison blocks held a matrix of toilets, one for each cell.

The original building was constructed in 1837 and planned according to the “Pennsylvania system” of incarceration, which was characterized by solitary confinement and an emphasis on rehabilitation over manual labor and corporal punishment. It’s one of the lesser works of the distinguished British architect John Haviland, who is better known for the revolutionary design of Eastern State Penitentiary. Through the early 1900s the Essex County Jail expanded to a capacity of 300. It was replaced by a new facility in 1970 and subsequently occupied by the county’s Bureau of Narcotics until 1989, when the building was deemed unsafe. In 2001, a catastrophic fire destroyed much of the structure. Reports of the place being inhabited by the homeless go back to the 1990s.

Two years after my first trip to the Essex County Jail, I came back with the resolve to see things through and a new exploring buddy. It had rained overnight and the constant dripping sounded just like footsteps, but otherwise the place seemed deserted. Objects left behind by recent inhabitants overshadowed any artifacts from the building’s early history, with garbage middens clustered in almost every cell. An hour or so in, I had my first anticlimactic encounter with a squatter, who greeted me politely and went about his business. Over the course of the morning, two others walked past me without saying a word. As scary as the place was, there were no monsters or maniacs living here, just a few people looking for a place to be left alone, finding a bleak kind of freedom in the most unlikely of places.

Rickety staircases led up through four stories of cells.

The stench of human waste emanated from a few of the rooms.

It was unnerving to wander these rows, not knowing when you might find someone inside.

Designed for a single occupant, each cell held a narrow bed and a toilet.

Approaching an empty cell.

An ornate stairway near the staff entrance differed from the stark verticals of the prison interior.

The Sea View Children’s Hospital

Forested views from a lower floor day room at Sea View Children’s Hospital.

At the turn of the twentieth century, tuberculosis was the second leading cause of death in the city and a major world health concern known to disproportionately affect the urban poor. In New York City, two-thirds of the 30,000 afflicted were dependent on city agencies for treatment. Growing concern from charitable organizations spurred the establishment of New York’s first public hospital designed exclusively to treat tuberculosis, care for the “sick, poor, and friendless,” and keep the epidemic under some measure of control by isolating sufferers from general hospitals. If you were diagnosed with tuberculosis in the early 1900s, your prognosis was grim. Lacking a cure, the only treatments thought to ease symptoms were fresh air, rest, sunshine, and good nutrition. A pleasant view was also considered essential for staving off depression. For this reason, hospital planners settled on a privately owned 25-acre hilltop parcel in rural Staten Island called “Ocean View,” just across from the already established New York City Farm Colony.

The plot was surrounded by a vast expanse of forested land (known as the Greenbelt today) which enabled the hospital grounds to expand as necessary. When Sea View Hospital was dedicated on November 12, 1913, the New York Times called it “the largest and finest hospital ever built for the care and treatment of those who suffer from tuberculosis.” The Commissioner of Public Charities claimed it was “a magnificent institution that is vast, ingenious, practical, convenient, sanitary, and beautiful, the greatest hospital ever planned in the world wide fight against the “white plague.” Though the new facilities effectively eased the suffering of tuberculosis patients and provided housing for the poor, little could be done to actually save lives in the long term. Most eventually succumbed to the disease.

Saplings take root in a light-filled solarium on the top floor. (Prints Available)

Two window fixtures had vanished, offering an unobstructed view of the surrounding woodlands.

Doorway into an open-air pavilion.

Hospital beds, cribs, and equipment left behind in a day room on a lower floor. (Prints Available)

In 1943, the development of the antibiotic streptomycin at Rutgers University led to a series of breakthroughs in the treatment of tuberculosis over the next decade, and much of that research took place at Sea View Hospital. The enthusiasm over these dramatic developments is captured in a 1952 report by the Department of Hospitals: “Euphoria swept Seaview Hospital. Patients consigned to death at the hands of the White Plague celebrated a new lease on life by dancing in the halls.” The transition was swift. By 1961, Sea View’s pavilions were practically emptied as patients miraculously recovered as a result of the new therapies. Today, a long-term care facility operates in several of the buildings and some structures have been repurposed by community agencies and civic groups, but much of the Sea View Hospital campus lies abandoned.

Past a fenced enclosure delineating the active section of the hospital, the grounds give way to the bramble-choked wilds of the Staten Island Greenbelt. The creepy ruins of the old women’s pavilions situated on the northern border are a popular detour on hikes from the neighboring boy scout camp. To the east lies the imposing Children’s Hospital, completed in 1938 and abandoned in 1974. Its spacious, window-lined solariums are typical of earlier Sea View wards, flanked on either side by open-air porches which were occupied by recovering patients 24 hours a day during the height of the epidemic. In an otherwise clinical Landmarks Preservation Commission report published in 1985, the researcher notes that “the building rises from a deep slope… Wooded surroundings, particularly dense to the east and south of the building, enhance the sense of isolation.” The view he’s describing is indeed one of New York City’s most surreal (pictured below in 2012).

The ominous Children’s Hospital, seen from a hilltop on the grounds of Sea View Hospital.

Reuse of the structure seems extremely unlikely given the large number of abandoned buildings within the active hospital complex that would make better candidates for restoration. Area conservationists are fighting to keep the surrounding woodlands protected from developers by making it a permanent part of the Greenbelt network of natural areas, and the building itself is nominally protected from demolition as part of Sea View Hospital’s historic district designation. That doesn’t mean that the building won’t serve a purpose as it continues to crumble. As I’ve mentioned in previous posts, Staten Island teenagers have a long history of voraciously exploring (and vandalizing) their local ruins. With the renovation of the Willowbrook State School in the 1990s, the later demolition of the Staten Island Monastery, and the impending restoration of the New York City Farm Colony, the isolated, under-the-radar Children’s Hospital may be next in line as the site of that requisite rite of passage. Only time will tell.

There’s little to suggest the building was used exclusively as a children’s hospital in its last years of operation.

Even the restrooms had windows for observation.

Drifts of plaster pile up on a table outside the darkroom.

The upright piano, an abandoned hospital staple.

“Dixie Cup for Dentures.” The name says it all.

A storage room in the attic had been pillaged.

A steep staircase led to the upper reaches of the utility floors.

Lowers floors were boarded up, which always allows for the eeriest light. (Prints Available)

The last room I came to was the most surprising–a boarded-up dayroom piled several feet high with hospital records.

IN OTHER NEWS… my friend Oriana Leckert‘s book “Brooklyn Spaces” is out this week. We’re a bit like kindred spirits, Oriana and I, but she goes more for the crowded, lively, and creative than the empty, eerie, and decrepit. The (50!) places profiled in the book show the authentic, human side of the global phenomenon that is “Brooklyn cool,” highlighting the heartfelt endeavors of a wave of culture makers that migrated to the borough for cheap rent and fashioned a network of bustling performance venues, art enclaves, and meeting places out of Brooklyn’s post-industrial landscape. Her obvious passion for offbeat museums, community gardens, communal living spaces, and out-there artist residencies is beyond infectious. Do yourself a favor and pick up a copy! And head to what I’m sure will be a raucous, sweaty launch party on May 30th.

IN OTHER NEWS… my friend Oriana Leckert‘s book “Brooklyn Spaces” is out this week. We’re a bit like kindred spirits, Oriana and I, but she goes more for the crowded, lively, and creative than the empty, eerie, and decrepit. The (50!) places profiled in the book show the authentic, human side of the global phenomenon that is “Brooklyn cool,” highlighting the heartfelt endeavors of a wave of culture makers that migrated to the borough for cheap rent and fashioned a network of bustling performance venues, art enclaves, and meeting places out of Brooklyn’s post-industrial landscape. Her obvious passion for offbeat museums, community gardens, communal living spaces, and out-there artist residencies is beyond infectious. Do yourself a favor and pick up a copy! And head to what I’m sure will be a raucous, sweaty launch party on May 30th.

Dredging the Archives + May 7th Library Lecture

The spooky Walloomsac Inn in Benington, VT is actually occupied as a private residence.

On Thursday, May 7th at 6:30 PM I’ll be presenting at the Mid-Manhattan Branch of the New York Public Library as part of their Author @ the Library series. This will be the last book talk I’m giving for a while, so if you’ve missed out on past events and would like to attend, now is the time. The best part is it’s totally free, open to the public, and there’s no need to register or buy a ticket. Head here for more info.

Since its release at the end of January, the book has gotten a great response, particularly on the world wide web. For the highlights, check out these bits in The New York Times, Wired, Complex, and Slate, who toured the Jumping Jack Pump House with me and captured it on video back in March.

I have some exciting posts in the works for you, but for now I wanted to share some images from the archive that haven’t been shown here before–places that didn’t warrant a full post for one reason or another, often because I couldn’t get inside, didn’t have time to poke around, or there just wasn’t a lot to see. Some of them are quite interesting nonetheless. Enjoy!

Sea View Hospital, Staten Island.

These mammoth LNG storage tanks in Rossville, SI were abandoned immediately after construction.

Ghost motel near Yosemite National Park.

San Francisco’s Fort Point. (not abandoned)

An abandoned house in Queens, now demolished.

A well-preserved surgeon’s residence at the Brooklyn Navy Yard Hospital.

An abandoned carriage house in Newport, RI locals call “the Bells.”