AbandonedNYC

new york city

Navigating the Sailor’s Infirmary

The Sailor’s Infirmary

In 1831, “An Act to Provide for Sick and Disabled Seamen” was passed by the New York State Legislature. A tract of farmland was acquired for the purpose, and by 1837, a proper hospital was constructed, funded by a head-tax imposed on sailors entering the Port of New York. The intention was admirable and the structure was impressive. Looking at the distinctively 19th-century facade of the old Sailor’s Infirmary today, it’s easy to imagine the place brimming with leathery old salts in their twilight years, regaling each other with adventures at sea that’d put Herman Melville to shame.

In those days, the porticos of the Infirmary offered commanding views of the New York Harbor and the surrounding countryside. In 1862, the Infirmary’s Chief Physician rhapsodized on the subject: “the weary invalid can breathe the bracing air of the sea…the sight of his chosen element, covered with the white winged messengers of a world-wide commerce that fills his mind with hope and cheer.”

Today, its pastoral surroundings have been swallowed up by development, the “white-winged messengers” have vanished from the harbor, and the halls of the hospital no longer resound with tales of youthful exploits in the exotic port cities of the world. Instead, a fire alarm near the front door blares interminably, to nobody at all.

The hospital as it appeared in 1887.

Expansive porches provided views of the harbor to ailing seamen.

While the idea of a hospital for sailors might seem odd to the modern observer, there was an urgent need for this sort of specialized care in the 19th century, when sailing was a much more common occupation and working conditions were deplorable. The Infirmary’s first Chief Physician described the health of a newly admitted patient in 1838 as such: “Arrived last night on brig from round Cape Horn…Has been to sea 118 days and had nothing but indifferent salt food to feed upon…Twenty days after sailing his gums became sore and spongy and bled very freely…Around the small of each leg caked hard and over the instep a deep blue almost black color…Suffered universal pain…Very much prostrated and emaciated and was brought into the (Infirmary)…Had no lime juice on board nor any other antiscorbutic effectual in preventing scurvy…It is in this shameful manner vessels are provided to the destruction of seamen…An object of pity to behold.”

In addition to advocating for better living and working conditions for seamen, the Sailor’s Infirmary made a lasting impact on world health as the birthplace of one of the most formidable biomedical research facilities in the world. In 1887, a young doctor founded a one-room bacteriological laboratory in the attic of the hospital to investigate epidemics like cholera and yellow fever. Over the course of the 20th century, his humble “Laboratory of Hygiene” evolved into a federally-funded research initiative that still operates today with an annual budget of $30 billion. Needless to say, it outgrew the attic long ago.

Researchers at work in the attic’s “Laboratory of Hygiene” (1887)

The attic as it appears today. The area was renovated in 1912.

Over the course of the 20th century the infirmary greatly expanded its services, and the campus grew to include a seven-story hospital and multiple ancillary buildings, dwarfing the original structure in the process. Under federal ownership, the grounds served military families, veterans, and later the general public. An organization of the Catholic medical system took over in 1981, and the hospital’s focus pivoted to psychiatric care and addiction rehabilitation. In recent years, the campus has been racked with financial problems, and its services have been consolidated to a few floors of the main hospital building. The rest of the complex sits abandoned, facing an uncertain future despite multiple landmark designations.

Like many grand, old buildings, the 1837 Infirmary appears to have been shut down from the top down. Dental clinics and early childhood programs lingered into the early 2000s on the lower floors, while the top floor sat unused for decades. Today, the interior is largely empty and plain—drop ceilings and fluorescent lights abound. But the attic retains a much older patina, and a few odd relics that feel fantastically out of step with the modern trappings below.

(Note: This is one of those rare abandoned buildings that isn’t vandalized beyond all recognition. In the hopes of keeping it that way I’ve chosen not to disclose its actual name and location, or to identify some key elements of its history.)

Teddy bear wallpaper and faux stained glass in an area used as a preschool.

Old hand painted lettering exposed under layers of chipped paint.

I’m not sure what the artist was going for here. Abstract rendering of a barn?

A bit of ornamentation was still visible on the stairs.

Upstairs in the attic, a fascinating pedal-operated sewing machine.

Mouldering files in the south wing.

Solid wood wardrobes were far older than furniture on the lower floors.

A red door led into a utility room.

Storage spaces in the attic held a number of intriguing artifacts.

Including a set of 1940s dental chairs.

In other news… I’ve got a new website that just went live. Head over to www.willellisphoto.com for a look at some of my other photo projects, plus a sampling of the work I do for a living (shooting non-abandoned architecture and interiors.) You can also sign up for my newsletter if you’re so inclined, or buy a book. (They’re 10% OFF with the code “ANYC.”)

Inside the Jumping Jack Power Plant

Lately the lack of abandoned buildings in the five boroughs has had me ruin-hunting on the distant shores of New Jersey and the Hudson River Valley. But all the while there was something incredible hiding in plain sight just a ten minute walk from my apartment. Just when it seems there is nothing left to find, this city will surprise you.

I had admired the building for some time, having first spotted it on a walk around my neighborhood a year or two ago. It was obviously some long-forgotten industrial relic, with a rather plain, but towering, facade. I had never heard of the place and could only find a single picture of it on the world wide web, with nothing of the interior. It seemed, at the time, that this could be one of the exceedingly rare “undiscovered” abandoned buildings in New York City. Who knew what it might look like inside? Most likely an empty shell, I thought, or else I would have heard of it.

It lingered long in my daydreams through the coming months, but I never attempted to stop in until December, when out of the blue I found myself walking in the direction of that mysterious building, camera and flashlight in hand. Inside, I couldn’t make out much at all but a collapsing ceiling and a floor padded with decades of rust and grime. I went looking for a way to the next level, finding several impassible staircases before settling on one that was relatively intact. Upstairs, I treaded over some rickety catwalks and continued into the main room.

With coal crunching underfoot, I gazed up at the grand four-story gallery of rusted machinery before me. It was likely about a century old, gleaming orange in its old age, scattered here and there with flecks of sunlight cast through the broken windowpanes on the south side of the hall. A hulking configuration of steel beams suspended over all, looking unmistakably like a man doing a jumping jack. Its actual function remains a mystery to me.

Judging by the amount of graffiti, I wasn’t even close to being the first person to find this place, and others have informed me that it’s fairly well-known among diehard explorers. After some careful inspection, it appears that some (though not all) of the graffiti is quite old, I’d guess from the late 70s and 80s judging by the style, and the way in which it has aged, rusting or peeling away with underlying layers of paint and metal.

Paper records from inside the building point to the year 1963 as the last time the plant was in operation. My theory is that the building had been abandoned and left pretty vulnerable to trespassers for a couple of decades before being sealed up tightly some time in the 80s or 90s. Until recently, it’s been relatively untouched since those days, making it something of a time capsule of a grittier New York. Prior to being secured, part of the ground floor was apparently used as a chop shop. An abandoned and gutted automobile had been walled in at some point, entombed like a mosquito in amber on the ground floor.

I can only speculate about what the building was actually used for. My guess would be a coal-burning power plant of some kind, though some artifacts refer to a “pump house.” (UPDATE: These records seem to refer to a separate building, which is still standing a few blocks away. In light of this, I’ve changed the name of this post to “Jumping Jack Power Plant” from “Jumping Jack Pump House”) I could tell you a bit more about its history but I don’t want to give away too much. “Undiscovered” or not, this place is still pretty under the radar, and I’d like to keep it that way for now.

A heartfelt thank you goes out to everyone who’s picked up a copy of my book, and for all of your thoughtful comments.

If you haven’t gotten yours yet, you can head over to abandonednycbook.com to order a signed copy and a free print directly from me, which is the best way to support what I do. (You can also get them on Amazon if you want to save a few bucks.)

It was so great meeting some of you at my Red Room talk last week. If you couldn’t make it to that one, you can still stop by one of these events this month and get your book that way. Hope to see you there!

- February 18th at Morbid Anatomy Museum (tickets here)

- February 23rd at Manhasset Public Library

- February 25th at WeWork Soho (tickets here)

Inside the Loew’s 46th St. Theater

A fire escape like this one on a windowless structure is a sure sign that a building was once a movie theater.

Some of the grandest and gaudiest heights of American architecture took form in the movie palaces of New York City in the early 20th century. While the majority of them have been converted to big box retail, gymnasiums, and McDonald’s restaurants, a handful have managed to slip through the cracks. Behind those hollow, graffiti-strewn walls you’ll find vestiges of movie-going’s golden age—a wonderland of molded plaster ornamentation dripping with sculptural details.

In the case of the former Loew’s 46th St. Theater in Borough Park, there’s no mistaking its former life. There is the telltale fire escape, the prodigious height, the ornate facade, even the old marquee remains. When it first opened under the name “Universal Theater” on October 9th, 1927, the Brooklyn Daily Eagle reported “one of the most disorderly first nights ever witnessed in Brooklyn.” That evening, a crowd of over 25,000 lined up to gain admittance to the 3,000 seat theater. Many resorted to clambering up the fire escape to gawk at the wonders within.

The Universal was New York City’s first “atmospheric theater,” masterminded by famed theater architect John Eberson. His design aimed to replicate an extravagant Italian garden under a night sky. Plastic trees and shrubbery extended from the wrapping facade, which was painted a fine gold, contrasting beautifully with the blue dome that suspended over all, giving the theater the feel of an open-air auditorium. The ceiling was once decked out with twinkling stars and projected with “atmospheric effects” (namely clouds) that constantly drifted by overhead.

After delighting a generation of Brooklynites with its fanciful design, the movie house fell on hard times with the rise of the multiplex. By the 1960s, the 46th St. Theater became a performance space and music venue. In November of 1970, the Grateful Dead played four quasi-legendary nights with the likes of Jefferson Airplane and the Byrds, and the theater was briefly known as the “Brooklyn Rock Palace.”

Neighbors soon tired of the noise and the rowdy concertgoers, and the venue closed down in 1973. A furniture retailer settled into the building, occupying the lobby and part of the ground floor of the theater with a showroom, and walling off the best bits from view. Seating was removed on the orchestra level, and the space was repurposed as a stock room. Though the building changed hands to a new furniture seller in the intervening years, the theater serves the same function to this day. The orchestra level is filled with an array of ornate upholstered chairs, creating an odd visual echo with the architectural arabesques overhead, made stranger by the fact that they’re all facing away from the screen.

For the record, the Loew’s 46th Street Theater is not the sort of place you should try sneaking in to. I had a fairly legitimate reason to be there when I scheduled an appointment last spring while scouting a location. After several phone calls to the secretary I managed to arrange a visit, where I was greeted by a friendly Hasidic man who let me inside and escorted me to the back of his store. He warned me that the place would be dark and it would take several minutes for the industrial-grade lighting to warm up. Little by little, the details emerged–gleaming balustrades, parapets, modillions, and entablatures fit for a Greco-Roman amphitheater.

For the next half hour or so, I had free reign to poke around and snap some pictures. I headed to the balcony, which was still relatively intact and offered better views. By the looks of it, no one bothered to sweep up after the last audience cleared the theater 45 years ago—popcorn bags, candy wrappers, and ticket stubs still litter the aisles. Through the grating buzz of the mercury vapor lamps, an imaginative mind could almost make out the surging strings of a Hollywood score or Jerry Garcia’s haunting refrain: “What a long, strange trip it’s been…”

As devoted Deadheads are wont to do, one fan managed to record the Grateful Dead’s full set list on the night of November 11th 1970, when they played the theater. Here’s “Truckin‘,” which makes for a compelling aural accompaniment to the images below. I especially enjoy the gentlemen’s “woohoo” at 1:10 when the lyrics mention his home town of New York City, such a classic concert moment.

If this location interests you, check out Matt Lambros’ excellent blog After the Final Curtain, which features an exhaustive record of decrepit movie palaces throughout the country (including this one.)

In the flickering light of the silver screen, the plaster detailing could easily be mistaken for solid gold.

The upper balcony’s decor is subtle by comparison, but the carpet featured an extravagant pattern that’s still visible today.

Switching gears now for a book update! If you’ve somehow missed it, the official release date of Abandoned NYC the book is January 28th, but as of yesterday I have them in stock (taking up half of my apartment) to start shipping out your orders a week early. It’s still not too late to get yours first (along with a print and a fancy signature!) by placing an order with me through this link. First shipment will go out next week (week of January 18th.)

I’ll also be giving a few talks next month, starting on February 4th at the Red Room of the KGB Bar, hosted by Untapped Cities. You can register here for a free ticket (there may be a drink minimum involved.) There is a limited capacity so make sure to sign up soon in case it fills up. On Wednesday February 18th, I’ll be doing a similar song and dance at the wonderful Morbid Anatomy Museum, tickets for that go for a low, low $5, you can get yours here or at the door. For any Long Islanders, I’ll be doing another talk/signing at the Manhasset Public Library hosted by the Great Neck Camera Club on the night of February 23rd. That one’s free, open to all, and there’s no need to register. I’m really, really looking forward to meeting some of you over the coming weeks and months! (And hopefully getting rid of these books so I can have my living room back…)

Thanks to everyone who’s already placed an order for all of the kind words and support!

Pick up a copy here.

Last Days of the Staten Island Farm Colony

Part of what makes abandoned buildings so captivating is that their existence is ephemeral, they cannot remain decayed and crumbling forever, and inevitably that means saying goodbye.

Admittedly, the Staten Island Farm Colony is not one of the most spectacular places I’ve seen, (the interiors have been completely destroyed by vandalism) but it remains the one place I’ve come back to more than any other. What’s always impressed me about it is its changeability. The place is reborn with every season, and I suppose that’s true of all abandoned buildings, but I’m always struck by it at the Farm Colony. In the height of summer, its jungle-like atmosphere lends it the look of a fallen Aztec empire, which is almost unrecognizable in the cooler months. It’s haunting in the fall when the fog rolls in, and desolate in the winter when ice and snow blanket the buildings inside and out. Through 40 years of abandonment, the Farm Colony is as ever-changing as the natural world that engulfs it, but it’s looking more and more definite that this historic district will be undergoing a final, permanent transformation in the days ahead.

Last month, the Landmarks Preservation Commission unanimously approved a proposal to bring 350 units of senior housing to the site, part of a large new development called “The Landmark Colony.” In the process, the institution is returning to its historic function as a home for the elderly after a four decade hiatus. (The place was essentially a geriatric hospital when it closed down in the 1970s, though it had been established in the mid 19th century as a refuge for the poor.) With five buildings saved and one kept as a stabilized ruin, the design will preserve much of the area’s architectural character. The remaining structures will be demolished and replaced with modern residential units, which is to be expected considering just how far gone some of these buildings are.

Several of the places I’ve photographed in the last few years have been set aside for renovation (The Domino Sugar Refinery, the Gowanus Batcave, and P.S. 186 to name a few.) The Smith Infirmary, the old Machpelah Cemetery office, and most troublingly, the Harlem Renaissance Ballroom have not been so lucky. It’s rare and encouraging when a structure is fortunate enough to get a second chance in this rapidly evolving city, but as positive as these changes are for their communities, a part of me still feels like something is lost. I know I’m not the only one who’ll miss the Farm Colony and its embattled ruins, which have become a popular spot for paintballers and Staten Island teenagers to pass the time.

Here’s a series of photos I’ve taken over the last year in sweltering heat, biting cold, snow, rain, and fog. Hopefully I make it back one last time before these ancient grounds are covered with fresh paint and brimming with active retirees year-round.

But a similar dormitory on the south side of the grounds will be stabilized and preserved as a ruin.

Trees silhouetted against the clouds, projected through a camera obscura on the ground floor of a residence hall.

Wandering Fort Wadsworth

Battery Weed looms over a desolate shoreline in Fort Wadsworth, Staten Island.

At the easternmost tip of Staten Island, a natural promontory thrusts over the seething Narrows of the New York Harbor, formed by glaciers thousands of years ago. The site’s geography most recently made it a prime location for the Verrazano Bridge, but its history as a popular scenic overlook and strategic defense post dates back to the birth of the nation. The British had occupied the area during the Revolutionary War, and its first permanent structures were built by the state of New York in the early 1800s. These fortifications safeguarded the New York Harbor during the War of 1812, but were abandoned shortly thereafter. So began the familiar cycle of ruin and rebirth that characterizes the history of Fort Wadsworth.

By the mid-19th century, these early structures had fallen into an attractive state of decay. In a time when all of Staten Island held a romantic appeal as an escape from the burgeoning industrialism of New York City, Fort Wadsworth in particular was known for its dramatic terrain, sweeping views of the harbor, and evocative old buildings. Herman Melville described the scene in 1839:

“…on the right hand side of the Narrows as you go out, the land is quite high; and on top of a fine cliff is a great castle or fort, all in ruins, and with trees growing round it… It was a beautiful place, as I remembered it, and very wonderful and romantic, too…On the side away from the water was a green grove of trees, very thick and shady and through this grove, in a sort of twilight you came to an arch in the wall of the fort…and all at once you came out into an open space in the middle of the castle. And there you would see cows grazing…and sheep clambering among the mossy ruins…Yes, the fort was a beautiful, quiet, and charming spot. I should like to build a little cottage in the middle of it, and live there all my life.”

Under the Verazzano Bridge.

The “castle” was demolished to make way for new fortifications constructed as part of the Third System of American coastal defense, known as Battery Weed and Fort Thompkins today. The batteries remain the fort’s most impressive and unifying structures, but they too were deemed obsolete as early as the 1870s due to advances in weaponry, and were used for little more than storage by the 1890s. At the turn of the 20th century, Fort Wadsworth entered yet another phase of military construction under the Endicott Board, when the United States made a nationwide effort to rethink and rebuild its antiquated coastal defenses. Like its predecessors, the Endicott batteries never saw combat, and were essentially abandoned after World War I.

Inside a powder room of Battery Catlin.

A squatter’s unmade bed in the back of the structure.

Though Fort Wadsworth was occupied by the military in various capacities until 1995, its defense structures went unused for most of the 20th century. By the 1980s, woods and invasive vines had covered areas that were once open fields, and Battery Weed was living up to its name, overtaken by mature trees and overgrowth. Since Fort Wadsworth was incorporated into the Gateway National Recreation Area in 1995, its major Third System forts (Battery Weed and Fort Thompkins) have been well maintained and properly secured, and upland housing and support buildings have been occupied by the Coast Guard, Army Reserve, and Park Police. But the headlands still retain an air of abandonment, due in large part to the condition of the Endicott Batteries, which remain off-limits to the public.

Over five of these batteries are scattered across the grounds, all in various states of disrepair.

The Endicott Batteries are filled with narrow, windowless rooms, tomblike hollows, and underground shafts.

Their military blandness stands out in contrast to the grace and grandeur of the fort’s earlier structures deemed worthy of preservation.

Layers of history peel back like an onion at Fort Wadsworth, as evidenced by a new discovery just unearthed by Hurricane Sandy. The storm caused a section of a cliff to collapse, downing several large trees and exposing the entrance to a previously unknown battery. Its vaulted granite construction places it firmly in the Third System, which means it was built around the time of the Civil War. Very little is known about the structure, except that it’s the only one of its kind at Fort Wadsworth. My best guess traces its partial construction to the 1870s, when Congress left many casemated fortifications unfinished by refusing to grant additional funding.

A previously unknown granite battery, possibly dating back to the Civil War, was unearthed by Hurricane Sandy.

Large mounds of soil block the interior of the battery from view.

They’d been sifted through ventilation shafts in the ceiling over decades of burial.

Over the mound, the vaulted structure leads deeper into the ground.

To my disappointment, the next room came to a dead end, and to my horror, it was crawling with hundreds of cave crickets. These blind half spider/half cricket monstrosities pass their time in the darkest, dampest, most inhospitable environments, and are known for devouring their own legs when they’re hungry. They give perspective to the level of isolation of this chamber, which likely stood underground for over a century.

What other mysteries still lie buried in the lunging cliffs of Fort Wadsworth, or the depths of this forgotten battery? The dirt may well conceal deeper rooms and darker discoveries…

Cave crickets in the deepest room of the forgotten battery.

Special thanks to Johnnie for the tip! Get in touch if you know of a historic, abandoned, or mysterious location in the five boroughs that’s worth exploring.

New York, Lost and Found

Through all of my travels in New York City’s neglected parks, waterways, and abandoned buildings, I’ve picked up a few souvenirs. Most of the time, I abide by the “leave nothing but footprints, take nothing but pictures” rule, but some objects I come across are too fascinating, too mysterious, or too grotesque to leave behind. You don’t find treasures like these on the bustling streets of Soho or Times Square, but out in the far-flung corners of the outer boroughs, or deep in the recesses of a long-abandoned building, things have a way of piling up and sticking around. These are a few of my favorite finds from an ongoing collection I call New York, Lost and Found. (see the rest here)

You wouldn’t expect to find doll parts in a Navy barracks, but somehow this misfit toy ended up in a crumbling hallway at Floyd Bennett Field, New York City’s first municipal airport. She’s got more to offer than an incredible hairstyle and a terrifying expression. Press the button on her navel, and those scaly arms come to life!

A stolen wallet lingered on the tracks of an abandoned railroad line in Queens for 25 years before I came across it. I attempted to track down the owner, but my search came up empty. (The credit cards expired in 1986.)

A stolen wallet lingered on the tracks of an abandoned railroad line in Queens for 25 years before I came across it. I attempted to track down the owner, but my search came up empty. (The credit cards expired in 1986.)

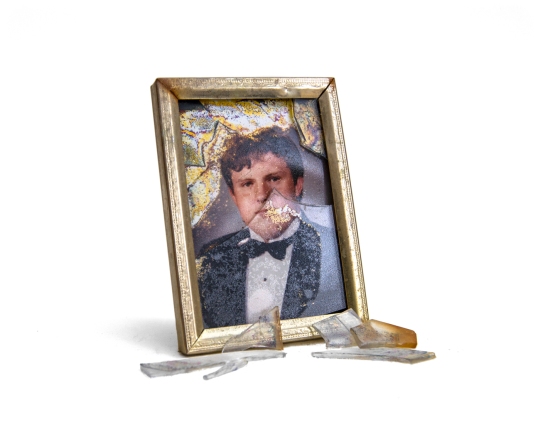

A dapper young man poses for a senior photo in this wallet-sized portrait I picked up in a junkyard on the Gowanus Canal.

A dapper young man poses for a senior photo in this wallet-sized portrait I picked up in a junkyard on the Gowanus Canal.

I came across this little card in an overgrown section of Owl’s Head Park in Bay Ridge, Brooklyn. “Please pardon my intrusion, but I am a DEAF-MUTE trying to earn a decent living. Would you help me by buying one of these cards.”

I came across this little card in an overgrown section of Owl’s Head Park in Bay Ridge, Brooklyn. “Please pardon my intrusion, but I am a DEAF-MUTE trying to earn a decent living. Would you help me by buying one of these cards.”

The quarantine hospital at North Brother Island has fewer artifacts than you might expect, but a maintenance building still held a nicely organized matrix of keys. I pocketed a handful of them, unable to resist their attractive sea foam patina. They’re pictured here with a raccoon bone, raccoons are the only mammals present on the island.

The quarantine hospital at North Brother Island has fewer artifacts than you might expect, but a maintenance building still held a nicely organized matrix of keys. I pocketed a handful of them, unable to resist their attractive sea foam patina. They’re pictured here with a raccoon bone, raccoons are the only mammals present on the island.

I spent several summers teaching animation and filmmaking to kids and teenagers in a repurposed chapel on Governors Island. A few years back, we had to vacate our beloved space when the building was slated for demolition, but I salvaged this hand-painted sign above the donation box on my way out. As far as I know, the Our Lady Star of the Sea Chapel is still standing, filled with old animation sets and crude clay characters from three summers ago.

I spent several summers teaching animation and filmmaking to kids and teenagers in a repurposed chapel on Governors Island. A few years back, we had to vacate our beloved space when the building was slated for demolition, but I salvaged this hand-painted sign above the donation box on my way out. As far as I know, the Our Lady Star of the Sea Chapel is still standing, filled with old animation sets and crude clay characters from three summers ago.

This photo was taped up in a bedroom of the Batcave squat in Gowanus, Brooklyn. The building’s inhabitants were evicted in the early aughts, but many of their belongings remained until recently—the structure is currently being renovated into artist studios. From what I can tell, the photo depicts the entrance to the Batcave, taken from the inside. It might not look like much, but the abandoned power station was home sweet home to many.

This photo was taped up in a bedroom of the Batcave squat in Gowanus, Brooklyn. The building’s inhabitants were evicted in the early aughts, but many of their belongings remained until recently—the structure is currently being renovated into artist studios. From what I can tell, the photo depicts the entrance to the Batcave, taken from the inside. It might not look like much, but the abandoned power station was home sweet home to many.

The fanciful Samuel R. Smith Infirmary was one of Staten Island’s greatest architectural treasures until the hospital met the wrecking ball in the spring of 2012. I found this old chair leg while touring the structure only a month or two before its demolition.

The fanciful Samuel R. Smith Infirmary was one of Staten Island’s greatest architectural treasures until the hospital met the wrecking ball in the spring of 2012. I found this old chair leg while touring the structure only a month or two before its demolition.

This wormeaten music book was left behind in a book room of P.S. 186 in Harlem that I didn’t notice until my second visit. Supposedly, the long-abandoned school is being renovated into affordable housing and a Boys and Girls Club.

This wormeaten music book was left behind in a book room of P.S. 186 in Harlem that I didn’t notice until my second visit. Supposedly, the long-abandoned school is being renovated into affordable housing and a Boys and Girls Club.

The pristine stretch of wilderness at Four Sparrow Marsh is concealed by a thick barrier of trees and overgrowth dotted with homeless encampments. Some spots are still occupied, but the individual who left this button behind was long gone. I found it pinned to his winter coat.

The pristine stretch of wilderness at Four Sparrow Marsh is concealed by a thick barrier of trees and overgrowth dotted with homeless encampments. Some spots are still occupied, but the individual who left this button behind was long gone. I found it pinned to his winter coat.

Beautiful ceramic mosaics are the most striking feature of the abandoned Sea View Hospital complex on Staten Island, located just across the street from the New York City Farm Colony. These seashells are used as design motif throughout the building.

Beautiful ceramic mosaics are the most striking feature of the abandoned Sea View Hospital complex on Staten Island, located just across the street from the New York City Farm Colony. These seashells are used as design motif throughout the building.

The warehouse at 160 Imlay St. is currently being renovated to luxury condominiums, but back in February of 2012, it was free to explore. This was the building that started it all for me; I walked in on a whim, and from then on, I was hooked. This rusty fire nozzle has sat on my mantle ever since.

The warehouse at 160 Imlay St. is currently being renovated to luxury condominiums, but back in February of 2012, it was free to explore. This was the building that started it all for me; I walked in on a whim, and from then on, I was hooked. This rusty fire nozzle has sat on my mantle ever since.

The eerie office at Machpelah Cemetery was neglected for decades before its demolition earlier this year. The place was pretty thoroughly ransacked when I visited, but I did find this coin bank in the back of a safe deposit vault. The bank itself is a souvenir from the 1939 New York World’s Fair, but the pennies inside date to the 1960s, 70s, and 80s. A coin minted in 1989 was the most recent addition, and likely coincides with the last year the building was occupied.

The eerie office at Machpelah Cemetery was neglected for decades before its demolition earlier this year. The place was pretty thoroughly ransacked when I visited, but I did find this coin bank in the back of a safe deposit vault. The bank itself is a souvenir from the 1939 New York World’s Fair, but the pennies inside date to the 1960s, 70s, and 80s. A coin minted in 1989 was the most recent addition, and likely coincides with the last year the building was occupied.

Waterlogged family photos were a tragic and ubiquitous sight in the aftermath of Hurricane Sandy. This was found several months after the disaster in a storm-ravaged park at Cedar Grove Beach, Staten Island.

Waterlogged family photos were a tragic and ubiquitous sight in the aftermath of Hurricane Sandy. This was found several months after the disaster in a storm-ravaged park at Cedar Grove Beach, Staten Island.

This tiny plastic shoe was found washed up on Dead Horse Bay in south Brooklyn, one of the best places in the city to find old things. The marshy area was filled in with garbage in the 1920s, but at some point, the landfill cap ruptured. Today, the shore is covered with old glass bottles and early plastic toys.

This tiny plastic shoe was found washed up on Dead Horse Bay in south Brooklyn, one of the best places in the city to find old things. The marshy area was filled in with garbage in the 1920s, but at some point, the landfill cap ruptured. Today, the shore is covered with old glass bottles and early plastic toys.

Another find from Dead Horse Bay. These “Lucky Joe” banks were manufactured by Nash’s Prepared Mustard in the 20s and 30s to celebrate the boxer Joe Louis. The container included a slotted lid that converted the jar to a coin bank once the contents were used up.

Another find from Dead Horse Bay. These “Lucky Joe” banks were manufactured by Nash’s Prepared Mustard in the 20s and 30s to celebrate the boxer Joe Louis. The container included a slotted lid that converted the jar to a coin bank once the contents were used up.

No bag of souvenirs from Dead Horse Bay is complete without a few horse bones. These are fairly commonplace and may date back far earlier than most of the garbage. They’re remnants of the area’s industrial age, when dead horses and offal were processed into glue and fertilizer.

No bag of souvenirs from Dead Horse Bay is complete without a few horse bones. These are fairly commonplace and may date back far earlier than most of the garbage. They’re remnants of the area’s industrial age, when dead horses and offal were processed into glue and fertilizer.

Getting Lost on North Brother Island

A tuberculosis pavilion crowns the treetops of North Brother Island like an Aztec ruin.

Most New Yorkers have never heard of North Brother Island, but they should take comfort in the fact that new trees are growing and manmade things are going by the wayside just a stone’s throw from Rikers and a few miles from LaGuardia Airport. New York City’s abandoned island proves that as much as we think we have a handle on things, nature is never far behind. Just give it time.

Many of the older structures are splitting at the seams, but there’s little hope or interest in preserving them.

In the case of North Brother Island, it took fifty years to transform a sparsely planted hospital campus to a bona fide wildlife sanctuary surging with fresh green life. Established as a city hospital for quarantinable diseases in 1885, it became a disreputable rehab center for adolescent drug addicts prior to its abandonment in the 1960s. To add to the intrigue, the island was the site of a catastrophic shipwreck and the residence of the notorious Typhoid Mary. (For a detailed history of Riverside Hospital, see Ian Ference’s thorough account over at the Kingston Lounge.) Today, opportunistic ivy floods the old lawns and races up the corners of the dormitories. Elsewhere, invasive kudzu—a Japanese import—holds at least an acre of land in its leafy grip. Few animals roam this untrodden landscape, with the exception of a handful of raccoons that took a dip in the East River and discovered the greenest place around.

An airplane takes off from nearby LaGuardia airport with a gantry crane in view.

Even though it’s one of the least inhabited places in New York City, you can still find pathways on North Brother Island. Parks employees and occasional visitors leave a network of rabbit trails on the forest floor, but they taper off on the south side, where a few ruins beckon you further into the weeds. I trudged through the brush for over an hour only to end up right back where I started, and it wouldn’t be the last time I was forced to admit defeat to the thorny wilds of Riverside Hospital. The island plays tricks on you, but it’s liberating to lose your way.

Surrealism made doubly surreal in a patient mural.

In order to protect the habitat and visitors from harm, North Brother Island is permanently closed to the public, and strictly off-limits during nesting season. Frequently patrolled due to its vicinity to Rikers, it’s known as one of the most difficult places in New York City to get to, which makes it an object of equal frustration and fascination for urban explorers near and far. (I was lucky enough to accompany a photographer with a long relationship with the Parks Department and a buddy with a boat—one or both are pretty essential if you’re trying to get here.)

The largest and most intriguing book I’ve ever seen was filled with the most mundane details.

If you never make it to North Brother Island, take heart in the fact that it’s best appreciated from afar, where distance allows the imagination to fill in the obscured reaches beneath its canopy and populate the crumbling towers visible on its shore. An abandoned island is the most natural thing in the world to romanticize, but in the light of day, the enigma dissolves. As menacing as the old buildings may appear, they’re ultimately indifferent.

But at day’s end, the sun slips low on the horizon and the ruins of Riverside Hospital begin to gleam. Our boat departs just as the light approaches a kind of golden splendor before winking into darkness. Receding from view as you near Barretto Point at sunset, North Brother Island regains a bit of its mystery. Come to think of it, no one’s ever been permitted to go there after dark…

Green leaves and blue skies illuminate a crumbling auditorium with jewel tones.

Inside the tuberculosis pavilion.

Metal barricades in an isolation room kept residents from breaking the windows.

Most of the hospital’s glass fixtures had been vandalized…

…but the island exhibits a near-complete lack of graffiti.

A spiral staircase in the former Nurses’ Residence.

Walls were stripped to their skeletons in this dormitory.

A doorway holds steady in a collapsed section of the Nurses’ Home, where a few saplings have taken root.

Talking Trash in Dubos Point Wildlife Sanctuary

Take the A train past JFK. You’ll be one of a handful of travelers left on a car that seemed well over capacity a moment ago; the babble of the crowd fades to the soft hum of an unimpeded machine. Nobody asks you for money, or directions. If you’ve made it this far, you know where you’re going.

Suddenly, the ground drops out and you’re gliding over the silver Jamaica Bay. The train runs just above sea level, skimming over a surface that teems visibly with diving cormorants. Clustered with skeletal boat frames, aged marinas jut from a neglected shoreline across the water, to the west, a row of painted houses stand on stilts. There’s no place like the Rockaways to experience New York as a city by the sea.

Head east at Hammels Wye, and a brief walk through the quiet neighborhood of Averne will lead you to a little known peninsula called Dubos Point, one of the last fragments of salt marsh left in a city that was once ringed with tidal wetlands. The marsh was filled with dredged materials in 1912 in preparation for an ill-fated real estate development, but over the last century, the area has reverted to its natural state. In 1988, the land was acquired by the Parks Department, deemed a wildlife sanctuary, and given an official name for the first time (Rene Dubos was a microbiologist and environmental activist who coined the phrase “Think Globally, Act Locally”).

Parks officials envisioned marked nature trails and boardwalks for community use, and planned to build nesting structures and employ part-time patrol staff to encourage wildlife and keep the place clean, but none of this came to be. The Audubon Society of New York maintained the grounds sporadically until 1999, but abandoned its post citing a lack of resources. Since then, the area has been largely neglected, leaving its care up to volunteers. Green Apple Corps and the Rockaway Waterfront Alliance have orchestrated several clean-up events over the years, but they’re facing an uphill battle.

Every day, the shores of Dubos Point are bombarded with an onslaught of garbage, and it’s not coming from park visitors (the preserve is technically not open to the public). Most of the refuse is washed up from the bay, after a long journey through storm drains that began in the littered streets of New York City. Familiar objects are made strange, touched by a long encounter with an invisible world, caked with green algae, eroded with salt, barnacle-burdened and bleached by the sun. The entire peninsula resounds with the constant susurration of wind through grass. For all these reeds are hiding, perhaps they whisper secrets; mud-moored vessels, decaying toys, and saltbored furniture lay half-concealed in the tidal growth.

Standing water in old tires and plastic debris makes for a perfect breeding ground for the area’s most populous species. My first steps onto the grounds of Dubos Point seemed to disturb some ancient curse, as great swarms of mosquitoes rose from their stagnant hollows to draw my blood sacrifice. The Parks department has been criticized in the past for neglecting its duties at Dubos Point while mosquito infestation reached “plague proportions” in the late 90s, rendering backyards unusable from April to October. After years of complaints and little improvement, some residents resorted to building outdoor shelters for brown bats, a natural insect predator. Today, the only visible improvement made on the grounds of Dubos Point is a line of Mosquito Magnet kiosks, placed every 100 feet along the boundary of the preserve.

Despite decades of pollution, the Jamaica Bay harbors hundreds of species of wildlife, and the water is cleaner today than it was 100 years ago. As one of the last remaining pockets of undeveloped land in New York, the estuary supplies an essential resting place for migratory birds along the Atlantic Flyway; egrets, herons, and peregrine falcons are spotted here. Looking past the garbage, you can still make out the natural beauty of Dubos Point, and imagine what this whole region was like 400 years ago. Neck-high cordgrass is abundant, trapping bits of decayed organisms to fuel a thriving, though limited, ecosystem. Throngs of fiddler crabs crowd the soggy ground, scuttling sideways with one collective mind, crunching underfoot like eggshells. The breezy silence is only interrupted by an occasional splash from a jumping fish, or the roar of a plane, taking off from the crowded runways of JFK just across the water. Off the curling tip of Dubos Point, fishermen still cast their lines in the Sommerville Basin, affirming a bond we’ve all but lost.

12,000 of the original 16,000 acres of wetlands around the Jamaica Bay have already been filled in for development, and sources predict that the last of the saltwater marshes could disappear in the next 20 years. It’s a shame to see one of the few protected areas in this condition, when its potential for education and recreation is so apparent. New York needs to protect its wild spaces, and sometimes that means getting our hands dirty. To learn about volunteer opportunities with the Parks Department, visit their website. And check back for information on the next Dubos Point clean-up.

Legend Tripping in Letchworth Village

Letchworth Village rests on a placid corner of rural Thiells, a hamlet west of Haverstraw set amid the gentle hills and vales of the surrounding Ramapos. A short stretch of modest farmhouses separates this former home for the mentally disabled from the serene Harriman State Park, New York’s second largest. Nature has been quick to reclaim its dominion over these unhallowed grounds, shrouding an unpleasant memory in a thick green veil. Abandonment becomes this “village of secrets,” intended from its inception to be unseen, forgotten, and silent as the tomb.

Owing to its reputed paranormal eccentricities, Letchworth Village has become a well-known subject of local legend. These strange tales had me spooked as I turned the corner onto Letchworth Village Road after a suspenseful two-hour drive from Brooklyn. Rounding a declining bend, I caught my first glimpse of Letchworth’s sprawling decay—some vine-encumbered ruin made momentarily visible through a stand of oak. Down the hazy horseshoe lanes of the boy’s ward, one by one, the ghosts came out.

By the end of 1911, the first phase of construction had completed on this 2,362 acre “state institution for the segregation of the epileptic and feeble-minded.” With architecture modeled after Monticello, the picturesque community was lauded as a model institution for the treatment of the developmentally disabled, a humane alternative to high-rise asylums, having been founded on several guiding principles that were revolutionary at the time.

The Minnisceongo Creek cuts the grounds in two, delineating areas for the two sexes which were meant never to mingle. Separate living and training facilities for children, able-bodied adults, and the infirm were not to exceed two stories or house over 70 inmates. Until the 1960s, the able-bodied labored on communal farms, raising enough food and livestock to feed the entire population.

Sinister by today’s standards, the “laboratory purpose” was another essential tenet of the Letchworth plan. Unable to give or deny consent, many children became unwitting test subjects—in 1950, the institution gained notoriety as the site of one of the first human trials of a still-experimental polio vaccine. Brain specimens were harvested from deceased residents and stored in jars of formaldehyde, put on display in the hospital lab. This horrific practice has become a favorite anecdote of ghost-hunters and adolescent explorers.

The well-intentioned plans for Letchworth Village didn’t hold up in practice, and by 1942, the population had swelled to twice its intended occupancy. From here, the severely underfunded facility fell into a lengthy decline. Many of the residents, whose condition necessitated ample time and attention for feeding, became seriously ill or malnourished as a result of overcrowding. At one point, over 500 patients slept on mattresses in hallways and dayrooms of the facility, meagerly attended by a completely overwhelmed staff tasked with the impossible.

Having discontinued the use of the majority of its structures, and relocated most of its charges into group homes, the institution closed down in 1996 as old methods of segregating the developmentally disabled were replaced with a trend toward normalization and inclusion into society. The state has made efforts to sell the property, with mixed results. Most of the dilapidated structures were slated for demolition in 2004 to make way for a 450-unit condo development, but the plan has evidently been put on hold. Ringed with ballfields and parking lots, shiny Fieldstone Middle School makes use of nine buildings of the former girl’s group, an island of promise in a landscape of failure.

Off Call Hollow Road, a new sign has been erected pointing out the “Old Letchworth Village Cemetery.” Down a seldom-traveled path, an unusual crop of T-shaped markers congregate on a dappled clearing. They’re graves, but they bear no names.

Few wished to remember their “defective” relatives, or have their family names inscribed in such a dishonorable cemetery—many family secrets are buried among these 900 deceased. Here, in the presence of so many human lives devalued, displaced, and forgotten, the sorrow of Letchworth Village is keenly felt.

As part of a movement taking place across the country, state agencies and advocates funded the installation of a permanent plaque inscribed with the names of these silent dead, and a fitting epitaph: “To Those Who Shall Not Be Forgotten.”

Moments after taking this photo, a group of young explorers entered through a side door. I gave them quite a scare.

A strange camera malfunction lasted the entire time I was in this building and stopped the moment I stepped out. It’s the closest I came to a paranormal experience.

Inside Harlem’s P.S. 186

School’s out forever; at least at P.S. 186. This aging beauty has loomed over West Harlem’s 145th Street for 111 years—but it’s been vacant exactly a third of that time. The Italian Renaissance structure was considered dilapidated when it shuttered 37 years ago, and today its interiors feel more sepulchral than scholastic.

Nature reclaims the school’s top floor.

Windows gape on four of its five stories, exposing classrooms to a barrage of elements. Spongy wood flooring, wafer-thin in spots, supports a profusion of weeds. Adolescent saplings reach upward through skylights and arch through windows. They’re stripped of their foliage on this unseasonably warm February morning, lending an atmosphere of melancholy to an already gloomy interior. Infused with an odor not unlike an antiquarian book collection, upper floors harbor a population of hundreds of mummified pigeon carcasses—the overall effect is grim. You’d never guess this building had an owner, but sure enough…

The site was purchased in 1986 by the nonprofit Boys and Girls Club of Harlem for $215,000 under the condition that new development would be completed within three years. After several decades of inactivity, the group introduced a redevelopment plan that called for the demolition of P.S. 186 and the construction of a 200,000 sq. ft. mixed-use facility with affordable housing, commercial and community space, and a new public school…

News of the school’s demolition mobilized area residents to save the structure. A series of local petitions and letter-writing campaigns championed the preservation of P.S. 186, and gained the support of the New York Landmarks Conservancy, though a landmark bid was blocked at a 2010 community board meeting. At the time, owners insisted that rehabilitating the decrepit building was a financial impossibility.

In a surprising turn of events, the BGCH recently downsized the plan in favor of preservation. The school will be renovated into 90 units of affordable housing and a new Boys and Girls Club.

It’s a rare victory for preservationists, and an unlikely one given the school’s history—when the building was last in use, community members wanted nothing more than to see the place razed.

In addition to generally run-down conditions, safety became a major concern at P.S. 186 in its final years. The H-shaped design allegedly had the potential to trap “hundreds of children and teachers” in the event of a fire. Doors on the bottom floor were to remain open at all times to keep the outdated floor plan up to code, leaving the building completely vulnerable to neighborhood crime.

According to the school’s principal at the time, “parents have been robbed in here at knife point, and people…use this building as a through-way.” In a 1972 incident, two youths, including the 17-year-old brother of a 5-year-old P.S. 186 student, broke into room 407 and raped a teacher’s aide at gunpoint.

Increasing community concern reached a boiling point earlier that year when 60 members of the African American empowerment group NEGRO (National Economic Growth and Reconstruction Organization) moved into the school to call for an evacuation of 600 students on the top three floors.

The stunt caught the attention of the Fire Department, who toured the school later that week. A deputy chief “didn’t see any real hazardous problem,” but was forced to evacuate the remaining 900 students when he was unable to activate the fire alarm. Inspectors discovered that wires leading out of the alarm system had been cut, although a school custodian claimed that the alarm system had worked during a routine test at 7:30 that morning.

By 1975, funding was at last approved for a replacement school, and much to the relief of parents, plans were put in place for the immediate demolition of the aging fire trap. Who could predict that thirty-seven years later P.S. 186 would be getting a second chance?

A few decades ago, this school was described as “antiquated,” “unsafe,” and “plain,” but today, it’s called “historic,” “magnificent,” and “beautifully designed.” This reversal illustrates the complex relationship we New Yorkers have with our buildings, and begs the question: what might the the thousands of old structures we see torn down every year have meant to us in a century?

It’s been a few months since I’ve set foot in the building, and today the visit feels like a half-remembered dream.

To keep vagrants out, cinderblocks had been installed in almost every window and door of the bottom floor. It looked too dark to shoot—but as my eyes started to adjust, I saw that light was finding its way in. Through every masonry crack and plaster aperture, bands of color projected onto decaying classrooms, vibrant variations on a pinhole camera effect. Past a vault inexplicably filled with tree limbs, a hall of camera obscuras each hosting an optical phenomenon more bewitching than the last. P.S. 186 is largely considered an eyesore in its current state, but who could deny that its interior is a thing of beauty?

However photogenic, this decay does little good for its underserved community—it’s the sort of oddity this city doesn’t have room for. Here’s a look inside, before we turn the page on what’s destined to be the most colorful chapter in the controversial, and continuing, history of this unofficial Harlem landmark.

-Will Ellis

Behind flaking slate chalkboards, pencilled measurements dating to their original installation in the early 1900s.