AbandonedNYC

Overgrown

The “Haunting” of Wyndclyffe Mansion

The Hudson River Valley is home to more than its share of formidable ruins, but few match the spooky appeal of Rhinebeck’s Wyndclyffe Mansion. Its beetle-browed exterior is blessed with that beguiling combination of gloom, ornamentation, and extreme old age that only the best haunted houses claim, and there’s no better time to witness them than late October, when autumn breezes send yellow leaves eddying through the hills and hollows of the old estate. It seems that the only thing this “haunted house” is missing is a good ghost story…

Much of what remains of the interior is far too unstable to access, this was taken from a window on the west side of the structure.

Murder, mayhem, and the supernatural don’t factor at all into the history of Wyndclyffe, but its past is compelling enough as it is. The manor was constructed in 1853 as the private country house of Elizabeth Schermerhorn Jones, who was a prominent member of an exceptionally wealthy New York family. Though palatial Hudson Valley estates were already in vogue among New York City’s ruling class, the magnificence of Wyndclyffe prompted neighboring aristocrats to throw even more money into their vacation homes so as not to be overshadowed by Elizabeth’s Rhinebeck abode. The house and the fury of construction it inspired is said to be the origin of the phrase, “keeping up with the Joneses.”

Elizabeth was the aunt of the great American author Edith Wharton, who is known for her keen, first-hand insight into the lives of America’s most privileged, which she brought to bear in classics like Ethan Frome, The House of Mirth, and The Age of Innocence, for which she won the Pulitzer Prize. (She’s also known for her ghost stories.) In her early youth, Edith would spend summers in the house, which was known by her as “Rhinecliff.” She portrayed it in less than laudatory terms in her late-career autobiography “A Backward Glance” (1934):

“The effect of terror produced by the house at Rhinecliff was no doubt due to what seemed to me its intolerable ugliness… I can still remember hating everything at Rhinecliff, which, as I saw, on rediscovering it some years later, was an expensive but dour specimen of Hudson River Gothic: and from the first I was obscurely conscious of a queer resemblance between the granitic exterior of Aunt Elizabeth and her grimly comfortable home, between her battlemented caps and the turrets of Rhinecliff.”

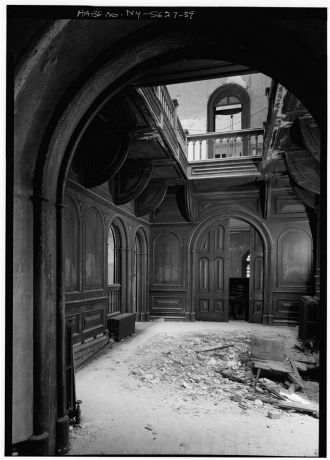

Many of the original architectural details are still visible in a collapsed section of the building, notice the wood detailing in the second floor parlor.

Her words bring to mind this passage from Shirley Jackson’s “The Haunting of Hill House” which describes the titular (fictional) structure:

“No human eye can isolate the unhappy coincidence of line and place which suggests evil in the face of a house, and yet somehow a maniac juxtaposition, a badly turned angle, some chance meeting of roof and sky, turned Hill House into a place of despair, more frightening because the face of Hill House seemed awake, with a watchfulness from the blank windows and a touch of glee in the eyebrow of a cornice. Almost any house…can catch up a beholder with a sense of fellowship; but a house arrogant and hating, never off guard, can only be evil.”

Here’s the same room pictured in the 1970s, with the floor already severely damaged by a leaky skylight.

The modern eye is likely to be much more merciful to the embattled Wyndclyffe, evil or no. Its beauty is readily apparent, and arguably enhanced, by the extent of decay it has suffered through 50 years of neglect. But how does a house as expensive, distinctive, and historically relevant as Wyndclyffe end up in such a state?

When Elizabeth passed away in 1876, Wyndclyffe was sold to a family who maintained the house into the 1920s, but the succession of owners that occupied the mansion through the Great Depression struggled to keep up with the costly repairs it required. In the 1970s, the house had already been abandoned for decades as the Hudson Valley’s status as a playground for the wealthy declined. At this point, the property was purchased and subdivided, which pared down the grounds of the estate from 80 acres to a paltry two and half. This action more than any other spelled doom for Wyndcliffe—notwithstanding the astronomical expense required to renovate a partially collapsed 160 year old mansion, the lack of land surrounding the structure has made it an extremely difficult sell to potential buyers. While many nearby estates have been renovated into thriving historic sites after a period of neglect, Wyndclyffe has struggled even to remain standing.

A glimmer of hope appeared in 2003 when a new owner cleared most of the trees and overgrowth from the grounds, erected a fence, and announced plans to save the mansion. But as is often the case, good intentions fade in the face of financial realities. Eleven years have come and gone and the meager improvements are difficult to discern—thick saplings, tangled thorns, and shrubbery completely envelop the structure once again, and the progress of decay marches on.

Numerous “No Trespassing” signs are posted around the property. State troopers are often summoned to the site when nearby homeowners alert them to suspicious activity.

Since Halloween is just around the corner, I’ll leave you with another eerie passage from Jackson’s “Haunting,” which is said by Stephen King (who should know) to be the best opening paragraph of any modern horror story. It deftly captures the uncanny appeal of empty buildings, and the persistent, however illogical, impression that a house continues to think, feel, and ruminate over its past long after it’s left behind by man.

“No live organism can continue for long to exist sanely under conditions of absolute reality; even larks and katydids are supposed, by some, to dream. Hill House, not sane, stood by itself against its hills, holding darkness within; it had stood so for eighty years and might stand for eighty more. Within, walls continued upright, bricks met neatly, floors were firm, and doors were sensibly shut: silence lay steadily against the wood and stone of Hill House, and whatever walked there, walked alone.”

Brooklyn Wild: Gravesend’s Accidental Park

An abandoned boat wades in a narrow cove between Calvert Vaux Park and the vacant lot.

It seems like every square inch of New York City has been categorized, labeled, and filled beyond capacity. But if you know where to look on the fringes of the city, you can still find places without names.

On the waterfront of Gravesend, Brooklyn, such a place still stands. It’s an all but untraveled wedge of vacant land, nestled between aging marinas and the northern border of Calvert Vaux Park on Bay 44th St. It’s a place I can only call “the secret park,” but there’s no mention of it on the department’s website. In its place, the all-knowing Google maps shows only a dull gray transected by the mysterious Westshore Avenue, though no such road exists.

A praying mantis seeks refuge in the tall grasses of the secret park.

The small peninsula was born out of the construction of the Verrazano Bridge in the 1960s when excavated material from the project was deposited on the shore of Gravesend Bay. Most of the new land was incorporated into the existing Drier-Offerman Park, but for some reason, this small finger of land was left out of the plan. Through the 1970s, it served as an illegal junkyard, but by 1982, developers came forward with a plan to construct a seaside residential development at the site. Apparently, the project never came to fruition. The city of New York suggests environmental remediation as a condition for future development.

Concrete construction debris can be found throughout the lot.

The peninsula has few trees aside from these saplings.

The ruins of an old marina rot on the northern edge of the property.

Lush foliage thrives in a wooded section behind the baseball fields of Calvert Vaux Park.

On the north shore of the peninsula, decaying pilings show the outline of a former pier and odd construction debris lie scattered throughout the landscape. A family of squatters lives comfortably out of industrial containers near the lot’s entrance, where a handful of abandoned watercraft comes to the surface at low tide. Beer cans and fire pits point to recent nights of youthful revelry, but by daytime, fishermen flock to this desolate place to cast their lines into the muddy gray waters of Gravesend Bay. At the shoreline, a few minutes of rock flipping will fetch you dozens of small green crabs. On a recent visit, I was amazed to meet two hunter/gatherers harvesting these fruits of the sea by the bucket, though I wasn’t tempted to try one.

I’d wager that it won’t be long before the development potential of the site is realized, but for the time being, the unkempt wilds of the secret park offer a rustic alternative to the paved walkways and manicured lawns of our city parks. If you’re ever looking to live off the land in New York City, you’d be hard-pressed to find a more suitable spot to pitch a tent.

A local man goes crab hunting.

The sun sets on a creek at the north side of Gravesend’s secret park.

Getting Lost on North Brother Island

A tuberculosis pavilion crowns the treetops of North Brother Island like an Aztec ruin.

Most New Yorkers have never heard of North Brother Island, but they should take comfort in the fact that new trees are growing and manmade things are going by the wayside just a stone’s throw from Rikers and a few miles from LaGuardia Airport. New York City’s abandoned island proves that as much as we think we have a handle on things, nature is never far behind. Just give it time.

Many of the older structures are splitting at the seams, but there’s little hope or interest in preserving them.

In the case of North Brother Island, it took fifty years to transform a sparsely planted hospital campus to a bona fide wildlife sanctuary surging with fresh green life. Established as a city hospital for quarantinable diseases in 1885, it became a disreputable rehab center for adolescent drug addicts prior to its abandonment in the 1960s. To add to the intrigue, the island was the site of a catastrophic shipwreck and the residence of the notorious Typhoid Mary. (For a detailed history of Riverside Hospital, see Ian Ference’s thorough account over at the Kingston Lounge.) Today, opportunistic ivy floods the old lawns and races up the corners of the dormitories. Elsewhere, invasive kudzu—a Japanese import—holds at least an acre of land in its leafy grip. Few animals roam this untrodden landscape, with the exception of a handful of raccoons that took a dip in the East River and discovered the greenest place around.

An airplane takes off from nearby LaGuardia airport with a gantry crane in view.

Even though it’s one of the least inhabited places in New York City, you can still find pathways on North Brother Island. Parks employees and occasional visitors leave a network of rabbit trails on the forest floor, but they taper off on the south side, where a few ruins beckon you further into the weeds. I trudged through the brush for over an hour only to end up right back where I started, and it wouldn’t be the last time I was forced to admit defeat to the thorny wilds of Riverside Hospital. The island plays tricks on you, but it’s liberating to lose your way.

Surrealism made doubly surreal in a patient mural.

In order to protect the habitat and visitors from harm, North Brother Island is permanently closed to the public, and strictly off-limits during nesting season. Frequently patrolled due to its vicinity to Rikers, it’s known as one of the most difficult places in New York City to get to, which makes it an object of equal frustration and fascination for urban explorers near and far. (I was lucky enough to accompany a photographer with a long relationship with the Parks Department and a buddy with a boat—one or both are pretty essential if you’re trying to get here.)

The largest and most intriguing book I’ve ever seen was filled with the most mundane details.

If you never make it to North Brother Island, take heart in the fact that it’s best appreciated from afar, where distance allows the imagination to fill in the obscured reaches beneath its canopy and populate the crumbling towers visible on its shore. An abandoned island is the most natural thing in the world to romanticize, but in the light of day, the enigma dissolves. As menacing as the old buildings may appear, they’re ultimately indifferent.

But at day’s end, the sun slips low on the horizon and the ruins of Riverside Hospital begin to gleam. Our boat departs just as the light approaches a kind of golden splendor before winking into darkness. Receding from view as you near Barretto Point at sunset, North Brother Island regains a bit of its mystery. Come to think of it, no one’s ever been permitted to go there after dark…

Green leaves and blue skies illuminate a crumbling auditorium with jewel tones.

Inside the tuberculosis pavilion.

Metal barricades in an isolation room kept residents from breaking the windows.

Most of the hospital’s glass fixtures had been vandalized…

…but the island exhibits a near-complete lack of graffiti.

A spiral staircase in the former Nurses’ Residence.

Walls were stripped to their skeletons in this dormitory.

A doorway holds steady in a collapsed section of the Nurses’ Home, where a few saplings have taken root.

Checking in to Grossinger’s Resort

The ransacked Paul G. hotel, showing the hallmarks of a recent paintball game.

Past a deserted security desk, waist-high grasses choke back the yawning entrance to the Jennie G. Hotel, whose toppled fence serves more as an invitation than a barrier. Here in the sleepy town of Liberty, NY, this derelict hilltop lodge is not only a destination for the curious, it’s a daily reminder of the town’s old eminence, an emblem of a dead industry, visible from miles around.

In its time, Grossinger’s Catskills Resort was a fantasy realized, where wealthy businessmen, celebrity entertainers, and star athletes gathered to mingle with those that they liked and were like, to see and be seen, and to enjoy, rightly so, the things they enjoyed. As the slogan goes—Grossinger’s has Everything for the Kind of Person who Likes to Come to Grossinger’s.

Flowers left by a former guest, or a prop from an old photo shoot.

If you’re the kind of person that’s inclined to spend their vacation somewhere dark, dusty, and dangerous, the motto still rings true today, and you’re not coming for the five-star kosher kitchen. For just as quickly as the resort prospered into a world-class institution, it’s descended into a swift decay. Explorers frequent the grounds, armed with cameras in an attempt to capture the beauty in its devastation, sifting through the artifacts—a broken lounge chair, old reservation records—piecing together a lost age of tourism.

A generation ago, this region of the Catskills was known as the Borscht Belt, a tongue-in-cheek designation for a string of hotels and resorts that catered to a predominantly Jewish customer base in a time when discrimination against Jews at mainstream resorts was widespread. In popular culture, the most notable representation of this time and place is Dirty Dancing, which was supposedly inspired by a summer at Grossinger’s. The unexpected success of its film adaptation had little effect on the long-struggling resort—in 1986, a year before the film was released, Grossinger’s ended its 70 year legacy.

The story of Grossinger’s is, at its root, an American story. The Grossingers were Austrian immigrants, who after some early years of struggle in New York City, and a failed farming venture, opened a small farmhouse to boarders in 1914, without plumbing or electricity. They quickly gained a reputation for their exceptional hospitality and incredible kosher cooking and outgrew the ramshackle farmhouse, purchasing the property that the resort still occupies today.

Grossinger’s rise to prominence is largely attributed to the couple’s daughter Jennie, who worked there as a hostess in its early years. Later, Jennie’s legendary leadership would transform the resort from its humble beginnings to a massive 35-building complex (with its own zip code and airstrip), attracting over 150,000 guests a year, and establishing a new type of travel destination that renounced the quiet charms of country living for a fast-paced, action-packed social experience that met the expectations of its sophisticated New York clientele.

Remnants of an attempt to burn down the Jennie G.

Every sport of leisure had its own arena, with state of the art facilities for handball, tennis, skiing, ice skating, barrel jumping, and tobogganing, along with a championship golf course. In 1952, the resort earned a place in history by being the first to use artificial snow. Its famous training establishment for boxers hosted seven world champions. Its stages launched the careers of countless well-known singers and comedians. In its day spas and beauty salons, ballrooms and auditoriums, guests were offered a level of luxury that even the wealthiest individuals couldn’t enjoy at home, earning Grossinger’s the nickname, “Waldorf in the Catskills.”

A daily missive called The Tattler identified notable guests and the business that made their respective fortunes. Weekly tabloids published on the grounds boasted the presence of celebrity athletes and entertainers. But for all the emphasis on earthly pleasures and material wealth, Jennie G. ensured that the Grossinger’s experience was warm and personal, always treating guests like one of the family, even when visitors reached well over 1,000 per week.

By the late sixties, the Grossinger’s model had started to fall out of favor as cheap air travel to tourist destinations around the world became readily available to a new generation. After the property was abandoned, several renovation attempts were aborted by a string of investors. Widespread demolition has greatly diminished the sprawl of the original resort, but several of the largest buildings remain. Most have been stripped of any vestige of opulence, and some structures are barely standing; no more so than the former Joy Cottage, whose floors might not withstand the footfalls of a field mouse.

Artifacts from the hotel’s glory days are few and far between, but Grossinger’s most recent batch of visitors has been quick to leave its mark. In a haunting hotel filled with empty rooms, some scenes are startlingly arranged, with collected mementos photogenically poised in the pursuit of a compelling shot. Despite these attempts to prettify Grossinger’s decline, the grounds retain an air of savage dilapidation, and an utter submission to nature.

An indoor swimming pool is Grossinger’s most enduring spectacle, and has become a favorite location of urban explorers near and far. Radiance remains in its terra-cotta tiles and its well-preserved space age light fixtures. Its dimensions continue to impress, as do the postcard views through its towering glass walls, all miraculously intact. It’s growth, not decay, that makes this pool so picturesque—the years have transformed this neglected natatorium into a flourishing greenhouse. Ferns prosper from a moss-caked poolside, unhindered by the tread of carefree vacationers, urged by a ceiling that constantly drips. Year-round scents of summer have bowed to a kind of perpetual spring, with the reek of chlorine and suntan lotion replaced by the heady odor of moss and mildew—it’s dank, green, and vibrantly alive.

Meanwhile, areas across the region that once relied on a thriving tourism industry have fallen into depression or emptied out. The Catskills is attempting to rebrand, updating its image and holding online contests to determine a new slogan. The winner? The Catskills, Always in Season.

Though it remains to be seen whether the coming seasons will bring new visitors, there’s no doubt they’re serving to erase the region’s outmoded reputation. With each passing year, in ruined hotels across the Catskills, the physical remnants of lost vacations dwindle. Indoors, snowdrifts weigh on aching floors; leaf litter collects to harbor the damp or fuel the fire. Vines claim what the rain leaves behind, compelling the constant progress of decay. Scattered in photo albums, hidden in bottom drawers, excerpted from yellowing newsprint, the memories will follow, clearing the way for new journeys. Before it’s forgotten, here’s one more look inside the celebrated resort.

This catwalk ensured a comfortable commute from your suite at the Paul G. to the indoor pool year-round.

A pitch-black beauty salon lit with the aid of a flashlight.

The ruined entrance to the hotel spa.

Office on the bottom floor of the Jennie G. Hotel.

The best preserved room, with two murphy beds, and a carpet of moss.

In most rooms, peeling wallpaper was all that remained.

The ground floor of the management office, now on the verge of collapse.

Hotel records neatly arranged on a mattress, by a photographer, no doubt.

The Trapps Mountain Hamlet, Backwoods Ghost Town

If you’re like me, city living can wear you down—sooner or later, you’re itching for the woods again. The sleepy college town of New Paltz offers a cheap motel and a short proximity to Mohonk Preserve, 5,000 acres of hiking trails, swimming holes, and rock scrambles nestled deep in the ancient Palisades. The world-worn hills of the Shawangunk Ridge evoke a pleasing sense of permanence to the weary New Yorker, it’s a lifetime away from the teeming avenues of Manhattan. Time seems to stand still around here, but out in these tall timbers, the ruins of a 19th century ghost town hint at a lost way of life.

The area is known for its landmark luxury resort, the Mohonk Mountain House, which has been run by the same family since it opened in 1869. True to its Quaker roots, the hotel originally banned liquor, dancing, and card playing; until 2006, it couldn’t claim a bar, and you still won’t find a TV or radio in any of the $700 a night lodgings. It may sound old-fashioned, but it’s part of a tradition in these parts—since they were first settled in the late 1700s, things have always been behind the times.

Before the age of mountain tourism, a small subsistence community lived off this land, growing what little food the thin, rocky soil could support, raising a handful of livestock, drinking from the Coxing and Peter’s Kills. They scraped a living carving millstone out of native rock, shaving barrel hoops, and harvesting tree bark for leather tanning. In the summer, women and children joined in harvesting huckleberries, a seasonal cash crop in wild abundance at the time.

With a peak population of forty or fifty families, the settlement included a hotel, a store, a chapel, and a one room schoolhouse. Despite this progress, the population held to its old ways. So hopelessly and wonderfully at odds with the changing values of the outside world, this oldfangled hamlet didn’t stand a chance.

Starting in the late 1800s, advances in technology gradually replaced the small trades of the Trapps. Unable to sell their traditional wares, settlers found work in neighboring resorts, including the Mohonk Mountain House, building hotels and maintaining trails and carriage roads. In the late 20s, the construction of Route 44 created a short term boom in the town’s employment, but eventually led to its decline.

Many sold their property to resort owners and headed to nearby villages to find a better way of life, but one man called Eli Van Leuven stayed behind, living in a tiny plank house without running water or electricity until his death in 1956.

The Van Leuven Cabin has been lovingly restored, an unassuming monument to a largely forgotten community. Aside from this, the humble industries of the two score families that resided here have left little to mark them but shallow depressions in the ground, rubble stacked in odd arrangements, and leaf-littered tombstones. Only a settlement so bound to the earth could disappear so completely.

On the drive home, the first sighting of the Manhattan skyline elicits a kind of dull horror, signaling the inevitable return to a concrete-bound existence. As I’m plunged back into the 21st century, the scene is at once overstimulating and shockingly mundane. In that moment, I’d take an axe and a cool morning in a mountain hamlet over any day in the ad-plastered streets of midtown, but the daydreams invariably dissolve. Out of habit, obligation, or common sense, I’ll forget the plank house for the brownstone, the Coxing Kill for the coffee shop, as the stony ruins of a mountain town blanket themselves in moss.

-Will Ellis

Former site of the Enderly House, most structures incorporated Native American techniques into their construction.

This road was built in large part by Trapps Hamlet residents. Today, it glides through the heart of the ghost town.

This boundary wall was used to delineate the property of Benjamin Fowler, who owned 150 acres for farming, livestock, and family use.

Many of Benjamin’s young children are buried in this forest plot. This grave for his son William is the earliest, dating to 1866.

Legend Tripping in Letchworth Village

Letchworth Village rests on a placid corner of rural Thiells, a hamlet west of Haverstraw set amid the gentle hills and vales of the surrounding Ramapos. A short stretch of modest farmhouses separates this former home for the mentally disabled from the serene Harriman State Park, New York’s second largest. Nature has been quick to reclaim its dominion over these unhallowed grounds, shrouding an unpleasant memory in a thick green veil. Abandonment becomes this “village of secrets,” intended from its inception to be unseen, forgotten, and silent as the tomb.

Owing to its reputed paranormal eccentricities, Letchworth Village has become a well-known subject of local legend. These strange tales had me spooked as I turned the corner onto Letchworth Village Road after a suspenseful two-hour drive from Brooklyn. Rounding a declining bend, I caught my first glimpse of Letchworth’s sprawling decay—some vine-encumbered ruin made momentarily visible through a stand of oak. Down the hazy horseshoe lanes of the boy’s ward, one by one, the ghosts came out.

By the end of 1911, the first phase of construction had completed on this 2,362 acre “state institution for the segregation of the epileptic and feeble-minded.” With architecture modeled after Monticello, the picturesque community was lauded as a model institution for the treatment of the developmentally disabled, a humane alternative to high-rise asylums, having been founded on several guiding principles that were revolutionary at the time.

The Minnisceongo Creek cuts the grounds in two, delineating areas for the two sexes which were meant never to mingle. Separate living and training facilities for children, able-bodied adults, and the infirm were not to exceed two stories or house over 70 inmates. Until the 1960s, the able-bodied labored on communal farms, raising enough food and livestock to feed the entire population.

Sinister by today’s standards, the “laboratory purpose” was another essential tenet of the Letchworth plan. Unable to give or deny consent, many children became unwitting test subjects—in 1950, the institution gained notoriety as the site of one of the first human trials of a still-experimental polio vaccine. Brain specimens were harvested from deceased residents and stored in jars of formaldehyde, put on display in the hospital lab. This horrific practice has become a favorite anecdote of ghost-hunters and adolescent explorers.

The well-intentioned plans for Letchworth Village didn’t hold up in practice, and by 1942, the population had swelled to twice its intended occupancy. From here, the severely underfunded facility fell into a lengthy decline. Many of the residents, whose condition necessitated ample time and attention for feeding, became seriously ill or malnourished as a result of overcrowding. At one point, over 500 patients slept on mattresses in hallways and dayrooms of the facility, meagerly attended by a completely overwhelmed staff tasked with the impossible.

Having discontinued the use of the majority of its structures, and relocated most of its charges into group homes, the institution closed down in 1996 as old methods of segregating the developmentally disabled were replaced with a trend toward normalization and inclusion into society. The state has made efforts to sell the property, with mixed results. Most of the dilapidated structures were slated for demolition in 2004 to make way for a 450-unit condo development, but the plan has evidently been put on hold. Ringed with ballfields and parking lots, shiny Fieldstone Middle School makes use of nine buildings of the former girl’s group, an island of promise in a landscape of failure.

Off Call Hollow Road, a new sign has been erected pointing out the “Old Letchworth Village Cemetery.” Down a seldom-traveled path, an unusual crop of T-shaped markers congregate on a dappled clearing. They’re graves, but they bear no names.

Few wished to remember their “defective” relatives, or have their family names inscribed in such a dishonorable cemetery—many family secrets are buried among these 900 deceased. Here, in the presence of so many human lives devalued, displaced, and forgotten, the sorrow of Letchworth Village is keenly felt.

As part of a movement taking place across the country, state agencies and advocates funded the installation of a permanent plaque inscribed with the names of these silent dead, and a fitting epitaph: “To Those Who Shall Not Be Forgotten.”

Moments after taking this photo, a group of young explorers entered through a side door. I gave them quite a scare.

A strange camera malfunction lasted the entire time I was in this building and stopped the moment I stepped out. It’s the closest I came to a paranormal experience.

Inside Harlem’s P.S. 186

School’s out forever; at least at P.S. 186. This aging beauty has loomed over West Harlem’s 145th Street for 111 years—but it’s been vacant exactly a third of that time. The Italian Renaissance structure was considered dilapidated when it shuttered 37 years ago, and today its interiors feel more sepulchral than scholastic.

Nature reclaims the school’s top floor.

Windows gape on four of its five stories, exposing classrooms to a barrage of elements. Spongy wood flooring, wafer-thin in spots, supports a profusion of weeds. Adolescent saplings reach upward through skylights and arch through windows. They’re stripped of their foliage on this unseasonably warm February morning, lending an atmosphere of melancholy to an already gloomy interior. Infused with an odor not unlike an antiquarian book collection, upper floors harbor a population of hundreds of mummified pigeon carcasses—the overall effect is grim. You’d never guess this building had an owner, but sure enough…

The site was purchased in 1986 by the nonprofit Boys and Girls Club of Harlem for $215,000 under the condition that new development would be completed within three years. After several decades of inactivity, the group introduced a redevelopment plan that called for the demolition of P.S. 186 and the construction of a 200,000 sq. ft. mixed-use facility with affordable housing, commercial and community space, and a new public school…

News of the school’s demolition mobilized area residents to save the structure. A series of local petitions and letter-writing campaigns championed the preservation of P.S. 186, and gained the support of the New York Landmarks Conservancy, though a landmark bid was blocked at a 2010 community board meeting. At the time, owners insisted that rehabilitating the decrepit building was a financial impossibility.

In a surprising turn of events, the BGCH recently downsized the plan in favor of preservation. The school will be renovated into 90 units of affordable housing and a new Boys and Girls Club.

It’s a rare victory for preservationists, and an unlikely one given the school’s history—when the building was last in use, community members wanted nothing more than to see the place razed.

In addition to generally run-down conditions, safety became a major concern at P.S. 186 in its final years. The H-shaped design allegedly had the potential to trap “hundreds of children and teachers” in the event of a fire. Doors on the bottom floor were to remain open at all times to keep the outdated floor plan up to code, leaving the building completely vulnerable to neighborhood crime.

According to the school’s principal at the time, “parents have been robbed in here at knife point, and people…use this building as a through-way.” In a 1972 incident, two youths, including the 17-year-old brother of a 5-year-old P.S. 186 student, broke into room 407 and raped a teacher’s aide at gunpoint.

Increasing community concern reached a boiling point earlier that year when 60 members of the African American empowerment group NEGRO (National Economic Growth and Reconstruction Organization) moved into the school to call for an evacuation of 600 students on the top three floors.

The stunt caught the attention of the Fire Department, who toured the school later that week. A deputy chief “didn’t see any real hazardous problem,” but was forced to evacuate the remaining 900 students when he was unable to activate the fire alarm. Inspectors discovered that wires leading out of the alarm system had been cut, although a school custodian claimed that the alarm system had worked during a routine test at 7:30 that morning.

By 1975, funding was at last approved for a replacement school, and much to the relief of parents, plans were put in place for the immediate demolition of the aging fire trap. Who could predict that thirty-seven years later P.S. 186 would be getting a second chance?

A few decades ago, this school was described as “antiquated,” “unsafe,” and “plain,” but today, it’s called “historic,” “magnificent,” and “beautifully designed.” This reversal illustrates the complex relationship we New Yorkers have with our buildings, and begs the question: what might the the thousands of old structures we see torn down every year have meant to us in a century?

It’s been a few months since I’ve set foot in the building, and today the visit feels like a half-remembered dream.

To keep vagrants out, cinderblocks had been installed in almost every window and door of the bottom floor. It looked too dark to shoot—but as my eyes started to adjust, I saw that light was finding its way in. Through every masonry crack and plaster aperture, bands of color projected onto decaying classrooms, vibrant variations on a pinhole camera effect. Past a vault inexplicably filled with tree limbs, a hall of camera obscuras each hosting an optical phenomenon more bewitching than the last. P.S. 186 is largely considered an eyesore in its current state, but who could deny that its interior is a thing of beauty?

However photogenic, this decay does little good for its underserved community—it’s the sort of oddity this city doesn’t have room for. Here’s a look inside, before we turn the page on what’s destined to be the most colorful chapter in the controversial, and continuing, history of this unofficial Harlem landmark.

-Will Ellis

Behind flaking slate chalkboards, pencilled measurements dating to their original installation in the early 1900s.

The Rockaway Beach Branch, Queens’ Forgotten Railroad

New York City’s narrowest jungle stretches across 3.5 miles of Central Queens, concealing the ruins of a rail line that’s been gathering rust for half a century. Abandoned by a bankrupt Long Island Railroad in 1962, the Rockaway Beach Branch is stirring debate today as opposing visions for its future emerge.

A passenger traveling on the Rockaway Beach Branch in the 1920s would board a southbound train at Whitepot Junction, pass through developing neighborhoods in Forest Hills, Glendale, Woodhaven, Richmond Hill, and Ozone Park, and traverse a burgeoning estuarine habitat called Jamaica Bay before arriving in the sandy Rockaways, then a popular vacation destination for privileged Manhattanites known as “New York’s Playground.” Today, the neighborhoods are flourishing, Jamaica Bay is losing 40 acres of marshland a year, and the isolated Rockaways are entering a stage of redevelopment.

The right-of-way was purchased by the city in the 1950s with plans to incorporate the entire line into its subway system, but the NYC Transit Authority ended up linking only the southern portion to the A train, cutting off the 3.5 mile stretch north of Rockaway Blvd. Through its 50 years of disuse, the remaining Rockaway Beach Branch has heard a stream of failed reuse and reactivation proposals as a forest has matured within its borders.

In 2005, community boards from Rego Park, Forest Hills, and other areas intersected by the line passed resolutions in favor of a linear park conversion, encouraged by the success of Manhattan’s High Line—a once abandoned rail line in Chelsea renovated into a futuristic above-ground park. According to the plan, bicycle paths and walkways would replace the derelict railroad, providing a much-needed green recreational space for the public. The Trust for Public Land is seeking private funding for a feasability study as a first step toward making the park, dubbed the “Queensway,” a reality. Beleaguered Rockaway commuters instead call for a reactivation of the line, which would provide a speedy link to Midtown Manhattan and a welcome alternative to the circuitous A-train. In response to this proposal, the MTA cites high operational and construction costs as deterrents to the project.

Trudging through this palsied limb of the New York City transit system, it’s hard to imagine either plan coming to fruition here, a place where few people venture and fewer have a good reason to. Detritus from teenage excursions and midnight meetings collect in piles along the forgotten spur—scrapped car parts, a coil of barbed wire, scores of bottles, a forsaken shopping cart, and most memorably, a discarded cleaver.

Trudging through this palsied limb of the New York City transit system, it’s hard to imagine either plan coming to fruition here, a place where few people venture and fewer have a good reason to. Detritus from teenage excursions and midnight meetings collect in piles along the forgotten spur—scrapped car parts, a coil of barbed wire, scores of bottles, a forsaken shopping cart, and most memorably, a discarded cleaver.

In a different season, the century-old rails would be obscured by vegetation, but they’re clearly visible on this brisk February afternoon. Forty-year-old birch and oak reclaim the soil, shoving aside iron rails assembled in the 1910s. Fallen branches and debris intersect a continuous line of tracks; most electrical towers still stand, others lay mired in the overgrowth. Leaves crunching under my feet alert a chain of backyard sentinels to my presence. Aside from the dogs and the postman, little else stirs in this quiet residential community; change is coming to the Rockaway Beach Branch—but it could take another 50 years to arrive.

A jagged weapon discarded on an overpass.

A nearby substation abandoned by the LIRR.