AbandonedNYC

urban exploration

Navigating the Sailor’s Infirmary

The Sailor’s Infirmary

In 1831, “An Act to Provide for Sick and Disabled Seamen” was passed by the New York State Legislature. A tract of farmland was acquired for the purpose, and by 1837, a proper hospital was constructed, funded by a head-tax imposed on sailors entering the Port of New York. The intention was admirable and the structure was impressive. Looking at the distinctively 19th-century facade of the old Sailor’s Infirmary today, it’s easy to imagine the place brimming with leathery old salts in their twilight years, regaling each other with adventures at sea that’d put Herman Melville to shame.

In those days, the porticos of the Infirmary offered commanding views of the New York Harbor and the surrounding countryside. In 1862, the Infirmary’s Chief Physician rhapsodized on the subject: “the weary invalid can breathe the bracing air of the sea…the sight of his chosen element, covered with the white winged messengers of a world-wide commerce that fills his mind with hope and cheer.”

Today, its pastoral surroundings have been swallowed up by development, the “white-winged messengers” have vanished from the harbor, and the halls of the hospital no longer resound with tales of youthful exploits in the exotic port cities of the world. Instead, a fire alarm near the front door blares interminably, to nobody at all.

The hospital as it appeared in 1887.

Expansive porches provided views of the harbor to ailing seamen.

While the idea of a hospital for sailors might seem odd to the modern observer, there was an urgent need for this sort of specialized care in the 19th century, when sailing was a much more common occupation and working conditions were deplorable. The Infirmary’s first Chief Physician described the health of a newly admitted patient in 1838 as such: “Arrived last night on brig from round Cape Horn…Has been to sea 118 days and had nothing but indifferent salt food to feed upon…Twenty days after sailing his gums became sore and spongy and bled very freely…Around the small of each leg caked hard and over the instep a deep blue almost black color…Suffered universal pain…Very much prostrated and emaciated and was brought into the (Infirmary)…Had no lime juice on board nor any other antiscorbutic effectual in preventing scurvy…It is in this shameful manner vessels are provided to the destruction of seamen…An object of pity to behold.”

In addition to advocating for better living and working conditions for seamen, the Sailor’s Infirmary made a lasting impact on world health as the birthplace of one of the most formidable biomedical research facilities in the world. In 1887, a young doctor founded a one-room bacteriological laboratory in the attic of the hospital to investigate epidemics like cholera and yellow fever. Over the course of the 20th century, his humble “Laboratory of Hygiene” evolved into a federally-funded research initiative that still operates today with an annual budget of $30 billion. Needless to say, it outgrew the attic long ago.

Researchers at work in the attic’s “Laboratory of Hygiene” (1887)

The attic as it appears today. The area was renovated in 1912.

Over the course of the 20th century the infirmary greatly expanded its services, and the campus grew to include a seven-story hospital and multiple ancillary buildings, dwarfing the original structure in the process. Under federal ownership, the grounds served military families, veterans, and later the general public. An organization of the Catholic medical system took over in 1981, and the hospital’s focus pivoted to psychiatric care and addiction rehabilitation. In recent years, the campus has been racked with financial problems, and its services have been consolidated to a few floors of the main hospital building. The rest of the complex sits abandoned, facing an uncertain future despite multiple landmark designations.

Like many grand, old buildings, the 1837 Infirmary appears to have been shut down from the top down. Dental clinics and early childhood programs lingered into the early 2000s on the lower floors, while the top floor sat unused for decades. Today, the interior is largely empty and plain—drop ceilings and fluorescent lights abound. But the attic retains a much older patina, and a few odd relics that feel fantastically out of step with the modern trappings below.

(Note: This is one of those rare abandoned buildings that isn’t vandalized beyond all recognition. In the hopes of keeping it that way I’ve chosen not to disclose its actual name and location, or to identify some key elements of its history.)

Teddy bear wallpaper and faux stained glass in an area used as a preschool.

Old hand painted lettering exposed under layers of chipped paint.

I’m not sure what the artist was going for here. Abstract rendering of a barn?

A bit of ornamentation was still visible on the stairs.

Upstairs in the attic, a fascinating pedal-operated sewing machine.

Mouldering files in the south wing.

Solid wood wardrobes were far older than furniture on the lower floors.

A red door led into a utility room.

Storage spaces in the attic held a number of intriguing artifacts.

Including a set of 1940s dental chairs.

In other news… I’ve got a new website that just went live. Head over to www.willellisphoto.com for a look at some of my other photo projects, plus a sampling of the work I do for a living (shooting non-abandoned architecture and interiors.) You can also sign up for my newsletter if you’re so inclined, or buy a book. (They’re 10% OFF with the code “ANYC.”)

Inside Rockland Psychiatric Center

An abandoned section of the former Rockland State Hospital, now known as Rockland Psychiatric Center.

In 1923, the New York state legislature passed a $50 million bond issue for the construction of new mental hospitals. After a disastrous fire at Ward’s Island in 1924, “where scores of mentally afflicted…were burned to death,” $11 million was set aside for a new campus designed specifically to relieve overcrowding at institutions in New York City. The town of Orangeburg, NY was chosen for its proximity to the five boroughs, picturesque surroundings, and “salubrious climate.”

The hospital once housed 9,000 people, including patients and staff.

With funding in place, the construction of the Rockland State Hospital for the Insane moved forward at a staggering pace. Townspeople looked on as the monstrous institution swallowed up tract after tract of farms, houses, and undeveloped land. As patients flooded into the new buildings by the thousands, escapes became a regular occurrence. The “potential menace” of this “new and formidable population of undesirable outsiders” was a cause of great concern for locals. Infrequent but grisly murders in the vicinity of the hospital were attributed to “mentally disturbed” escapees. But the real horrors were occurring on the inside, as many of Orangeburg’s citizens could personally attest to–the institution was one of the largest job providers in the county.

Chipped plaster, masonry, paint, and wallpaper fill a water basin.

The real trouble started during World War II, when lucrative war industry jobs lured much of the staff away and a large number of Rockland’s male attendants left to join the armed forces. As the population soared to nearly 9,000, patient-to-staff ratios plummeted. “The work is hard, disagreeable and frequently dangerous, and the hospital has found it next to impossible to recruit employees.” New hires during this period were often untrained and unqualified. From a 1940s Times article: “An employment bureau in New York City sent a number of applicants here, but most of them were found to be suffering from arthritis, cardiac ailments or “unnatural” temperament and had to be sent home. ‘Some of them should be patients,’ Dr. Blaisdell said.”

A stash of nudie magazines hidden long ago in the basement of a kitchen area.

Like most all institutions operating during this period, the overcrowding and lack of effective treatment led to systemic abuse and negligence. Until the development of antipsychotic drugs in the 1960s, shock therapy and lobotomy were the only treatment methods available for severe cases of schizophrenia and other mental illnesses. As the century progressed and the new drugs became readily available, most patients were able to live independently outside of the asylum system. Since the 1970s, Rockland Psychiatric Center (as it is now known) has predominantly been used as an outpatient facility. By 1999 it housed less than 600 patients. Several new facilities were constructed in more recent years for outpatient care, but vast expanses of the 600 acre campus are entirely empty.

Mattresses piled up in a dayroom.

Today, a grid of overgrown streets divides a vast configuration of maze-like buildings known only by number. These were separate wards for men, women, children, and other subsets of the population like the infirm, the violent, and the criminally insane. Others were workshops, auditoriums, power plants, administration buildings, staff housing… the list goes on and on.

Exploring the buildings can be confusing and perilous. One ward’s heavy wooden doors had the nasty habit of slamming shut and refusing to open again, which can be a serious situation when there’s only one or two ways out. My solution was a series of improvised doorstops–beer cans, scraps of debris, whatever I could get my hands on–which doubled as a trail of breadcrumbs to give me a reasonable hope of finding my way out again.

One of Rockland’s most interesting features is the old four lane bowling alley. It’s a heavily trafficked area full of tempting props. Pins, balls, shoes, and trophies have been endlessly moved around, manipulated, and arranged into perfect triangles in the middle of the lanes. While I don’t blame fellow photographers for this sort of thing, it can be disappointing to walk into something that looks more like a stage set than a wild, unpredictable ruin. I’ll take that over the mindless graffiti–some if which I removed with a little Photoshop magic in the images below.

Despite all the modern mischief making, the bowling alley represents the best intentions of the institution to provide quality of life to patients who spent their lives at Rockland. These lanes must have been a welcome distraction from the monotony of asylum living.

Stay tuned for an upcoming post on the Rockland Children’s Hospital, which features an impressive collection of WPA murals.

A well-preserved bowling alley was located on the ground floor of a recreation building.

Blank score sheets could be found behind the ball return.

The AMF bowling equipment may date back to the 60s or 70s.

Bowling balls pile up at the end of the lanes from previous visitors.

Compared to the bowling balls, the pins were scarce. Many had been stolen over the years.

Wood shelving used for bowling shoes, once arranged by size.

Trophies for male and female bowlers.

Inside the Jumping Jack Power Plant

Lately the lack of abandoned buildings in the five boroughs has had me ruin-hunting on the distant shores of New Jersey and the Hudson River Valley. But all the while there was something incredible hiding in plain sight just a ten minute walk from my apartment. Just when it seems there is nothing left to find, this city will surprise you.

I had admired the building for some time, having first spotted it on a walk around my neighborhood a year or two ago. It was obviously some long-forgotten industrial relic, with a rather plain, but towering, facade. I had never heard of the place and could only find a single picture of it on the world wide web, with nothing of the interior. It seemed, at the time, that this could be one of the exceedingly rare “undiscovered” abandoned buildings in New York City. Who knew what it might look like inside? Most likely an empty shell, I thought, or else I would have heard of it.

It lingered long in my daydreams through the coming months, but I never attempted to stop in until December, when out of the blue I found myself walking in the direction of that mysterious building, camera and flashlight in hand. Inside, I couldn’t make out much at all but a collapsing ceiling and a floor padded with decades of rust and grime. I went looking for a way to the next level, finding several impassible staircases before settling on one that was relatively intact. Upstairs, I treaded over some rickety catwalks and continued into the main room.

With coal crunching underfoot, I gazed up at the grand four-story gallery of rusted machinery before me. It was likely about a century old, gleaming orange in its old age, scattered here and there with flecks of sunlight cast through the broken windowpanes on the south side of the hall. A hulking configuration of steel beams suspended over all, looking unmistakably like a man doing a jumping jack. Its actual function remains a mystery to me.

Judging by the amount of graffiti, I wasn’t even close to being the first person to find this place, and others have informed me that it’s fairly well-known among diehard explorers. After some careful inspection, it appears that some (though not all) of the graffiti is quite old, I’d guess from the late 70s and 80s judging by the style, and the way in which it has aged, rusting or peeling away with underlying layers of paint and metal.

Paper records from inside the building point to the year 1963 as the last time the plant was in operation. My theory is that the building had been abandoned and left pretty vulnerable to trespassers for a couple of decades before being sealed up tightly some time in the 80s or 90s. Until recently, it’s been relatively untouched since those days, making it something of a time capsule of a grittier New York. Prior to being secured, part of the ground floor was apparently used as a chop shop. An abandoned and gutted automobile had been walled in at some point, entombed like a mosquito in amber on the ground floor.

I can only speculate about what the building was actually used for. My guess would be a coal-burning power plant of some kind, though some artifacts refer to a “pump house.” (UPDATE: These records seem to refer to a separate building, which is still standing a few blocks away. In light of this, I’ve changed the name of this post to “Jumping Jack Power Plant” from “Jumping Jack Pump House”) I could tell you a bit more about its history but I don’t want to give away too much. “Undiscovered” or not, this place is still pretty under the radar, and I’d like to keep it that way for now.

A heartfelt thank you goes out to everyone who’s picked up a copy of my book, and for all of your thoughtful comments.

If you haven’t gotten yours yet, you can head over to abandonednycbook.com to order a signed copy and a free print directly from me, which is the best way to support what I do. (You can also get them on Amazon if you want to save a few bucks.)

It was so great meeting some of you at my Red Room talk last week. If you couldn’t make it to that one, you can still stop by one of these events this month and get your book that way. Hope to see you there!

- February 18th at Morbid Anatomy Museum (tickets here)

- February 23rd at Manhasset Public Library

- February 25th at WeWork Soho (tickets here)

Kings Park Psychiatric Center’s Building 93

Kings Park Psychiatric Center’s Building 93

The ruins of Long Island’s Kings Park Psychiatric Center are often described as the perfect setting for a horror movie, and sure enough, several have been shot here. Poe and Lovecraft’s narrators may have been writing from asylum cells, but today’s horror heroes are venturing inside the abandoned ones. As shuttered institutions across the United States fall into decay, the insane asylum is showing up with increasing regularity in our scary movies, TV shows, books, and urban legends, quickly becoming synonymous with vengeful spirits, villainous doctors, and murderous mental patients. But while we may enjoy the “thrill of the shudder” while looking back at these places, we should be wary of reinforcing the stigma of mental illness and overlooking the nuanced history of American institutions.

A craft room on the ground floor still held looms and half finished rugs. (Prints Available)

Established in 1885 by the city of Brooklyn prior to the consolidation of the five boroughs, Kings County Asylum followed the farm colony model popular at the time, designed as a self-sufficient community where residents were put to work raising crops and livestock to support the sprawling campus. The labor was thought to be therapeutic, occupying the time and attention of residents and keeping costs down. Early in its history, Kings Park was composed of a group of cottages meant to avoid the high rise asylum model which was already viewed as inhumane. But demand soared as the population skyrocketed in New York City into the 1930s, and in 1939 the institution resorted to constructing Building 93, a 13-story structure whose design was strikingly similar to what it had sought to avoid. At its peak in the 1950s, Kings Park reached a population of over 9,000 residents, who were divided by gender, age, temperament, and physical limitations through a complex of over 100 buildings, which included power plants, fire stations, staff housing, hospitals, recreational facilities, piggeries, and cow barns.

Beds may have been moved down in 1996 when Kings Park’s last residents were relocated to nearby Pilgrim State.

Furniture and equipment left behind on the ground floor.

Throughout its history, Kings Park was notable for staying on the cutting edge of psychological science, cementing its place in history as an early adopter and proponent of a succession of new procedures and medications that eventually led to the institution’s decline. In the first half of the 20th century, the psychological community was in a state of desperation, charged with the task of caring for a growing number of mentally ill patients with few treatment options available aside from psychotherapy and the rampant use of restraints and confinement. The 1940s saw the rise of two groundbreaking, albeit crude, procedures that gave doctors effective tools to manage extremely disturbed patients for the first time.

Shock therapy was conceived when doctors observed that the mood of epileptic patients suffering from depression improved after a seizure. The procedure aimed to replicate these benefits by inducing a seizure through electricity or insulin injection. Electroconvulsive therapy, as it’s known today, is still considered an effective treatment, even having a resurgence in recent years. But today’s advanced anesthesia and precise control of the duration and physical effects of seizures is a far cry from what patients went through in the 1940s. Strapped fully conscious to a hospital bed, patients could convulse for up to fifteen minutes at a time, often with enough force to fracture and break bones. Once a patient was admitted to an asylum, they had no right to give or deny consent for these procedures, and in many cases, shock therapy was used as a punitive measure to keep unruly residents in line.

Early diagram of a transorbital lobotomy.

The lobotomy is remembered as one of the most grotesque treatment methods of the era. It was a simple procedure, in which a metal tool was inserted through the eye socket into the skull cavity, and wrenched around to sever the connections of the pre-frontal cortex from the rest of the brain. It was an imprecise and brutal operation, which left lobotomized individuals with no trace of their former selves. Though proponents of the procedure called these results a “second childhood,” lobotomized patients might have been more accurately described as zombies—extremely violent and disturbed residents would be rendered permanently docile, passive, and easy to control. Though it was controversial even in its time, its first proponents were awarded a Nobel Peace Prize in 1949 for their discovery.

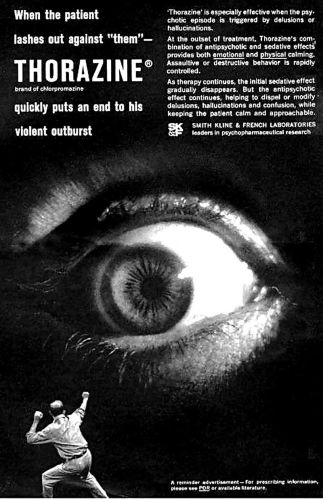

A 1960s advertisement for antipsychotic medication.

The development of effective antipsychotic medication in the mid-1950s signaled the decline of these extreme measures and the institution system as a whole. For the first time, residents once considered hopeless were able to manage their mental illness and live independently. This led to a dramatic shift in institutions across the country from severe overcrowding to near-abandonment as a trend of deinstitutionalization swept through America into the 80s and 90s. But as anxious as the powers that be were to put this dark period of history behind them (and cut funding out of state budgets,) they may have done too much too soon. While medication has made it possible for most people living with severe mental disorders to function on their own, there is still a sizable percentage for whom the available medications are ineffective. Reputable group homes for the mentally ill are few and far between, and out of reach for individuals without a solid support system in place. Many suffering from severe mental illness today are living on the streets, and a growing number end up incarcerated, without proper access to quality psychiatric care. Today, Kings Park stands as a testament to a bygone era, but the problem it sought to address remains unsolved.

Layers of colored paint peel from a hallway of isolation rooms. (Prints Available)

Lower floors housed able-bodied residents with large day rooms, while the infirm were confined to the upper levels.

Each floor was nearly identical, with subtle variations in color and layout.

A central hallway connected day rooms, dormitories, dining halls, and isolation chambers. (Prints Available)

Patient rooms leading to the cafeteria.

Vines overtaking the exterior of Building 93.

Check out Part 1 of “A History Abandoned” from Vocativ.com, which follows me on an exploration through three NYC institutions. First up, Kings Park:

Green Thumbing Through the Boyce Thompson Institute

The abandoned Boyce Thompson Institute in Yonkers.

In 1925, Dr. William Crocker spoke eloquently on the nature of botany: “The dependence of man upon plants is intimate and many sided. No science is more fundamental to life and more immediately and multifariously practical than plant science. We have here around us enough unsolved riddles to tax the best scientific genius for centuries to come.”

As the director of the Boyce Thompson Institute in Yonkers, Crocker was charged with leading teams of botanists, chemists, protozoologists, and entomologists in tackling the greatest mysteries of the botanical world, focusing on cures for plant diseases and tactics to increase agricultural yields. The facility was opened in 1924 as the most well equipped botanical laboratory in the world, with a system of eight greenhouses and indoor facilities for “nature faking”—growing plants in artificial conditions with precise control over light, temperature, humidity, and carbon dioxide levels.

The sun sets on the greenhouses of the Boyce Thompson Institute.

The institution had been founded by Col. William Boyce Thompson, a wealthy mining mogul who became interested in the study of plants after witnessing starvation while being stationed in Russia, (although an alternate history claims he just loved his garden.) Recognizing the rapid rate of population growth worldwide, he sought to establish a research facility with an eye toward increasing the world’s food supply, “to study why and how plants grow, why they languish or thrive, how their diseases may be conquered and how their development may be stimulated.”

By 1974, the Institute had gained an international reputation for its contributions to plant research, but was beginning to set its sights on a new building. The location had originally been chosen due to its close proximity to Col. Thompson’s 67-room mansion Alder Manor, but property values had risen sharply as the area became widely developed. Soaring air pollution in Yonkers enabled several important experiments at the institute, but hindered most. With a dwindling endowment, the BTI moved to a new location at Cornell University in Ithaca, and continues to dedicate itself to quality research in plant science.

Most of the interiors had a near-complete lack of architectural ornament, but the entryway was built to impress.

The city purchased the property in 1999 hoping to establish an alternative school, but ended up putting the site on the market instead. A developer attempted to buy it in 2005 with plans to knock down the historic structures and build a wellness center, prompting a landmarking effort that was eventually shot down by the city council. The developer ultimately backed out, and the buildings were once again allowed to decay. Last November, the City of Yonkers issued a request for proposals for the site, favoring adaptive reuse of the existing facilities. Paperwork is due in January.

Until then, the grounds achieve a kind of poetic symmetry in warmer months, when wild vegetation consumes the empty greenhouses, encroaching on the ruins of this venerable botanical institute…

-Will Ellis

Ornate balusters made this staircase the most attractive area of the laboratory.

A central oculus leads to this mysterious pen in the attic.

This stone sphere had been the centerpiece of the back facade, until someone decided to push it down this staircase. See its original location here.

The city gave up on keeping the place secured long ago.

The north wing had been gutted at some point.

An interesting phenomenon in the basement–a population of feral cats had stockpiled decades worth of food containers left by well-meaning cat lovers.

A view from the upstairs landing was mostly pastoral 75 years ago.

The main building connects to a network of intricate greenhouses.

The interiors were covered with shattered glass, but still enchanting.

Checking in to Grossinger’s Resort

The ransacked Paul G. hotel, showing the hallmarks of a recent paintball game.

Past a deserted security desk, waist-high grasses choke back the yawning entrance to the Jennie G. Hotel, whose toppled fence serves more as an invitation than a barrier. Here in the sleepy town of Liberty, NY, this derelict hilltop lodge is not only a destination for the curious, it’s a daily reminder of the town’s old eminence, an emblem of a dead industry, visible from miles around.

In its time, Grossinger’s Catskills Resort was a fantasy realized, where wealthy businessmen, celebrity entertainers, and star athletes gathered to mingle with those that they liked and were like, to see and be seen, and to enjoy, rightly so, the things they enjoyed. As the slogan goes—Grossinger’s has Everything for the Kind of Person who Likes to Come to Grossinger’s.

Flowers left by a former guest, or a prop from an old photo shoot.

If you’re the kind of person that’s inclined to spend their vacation somewhere dark, dusty, and dangerous, the motto still rings true today, and you’re not coming for the five-star kosher kitchen. For just as quickly as the resort prospered into a world-class institution, it’s descended into a swift decay. Explorers frequent the grounds, armed with cameras in an attempt to capture the beauty in its devastation, sifting through the artifacts—a broken lounge chair, old reservation records—piecing together a lost age of tourism.

A generation ago, this region of the Catskills was known as the Borscht Belt, a tongue-in-cheek designation for a string of hotels and resorts that catered to a predominantly Jewish customer base in a time when discrimination against Jews at mainstream resorts was widespread. In popular culture, the most notable representation of this time and place is Dirty Dancing, which was supposedly inspired by a summer at Grossinger’s. The unexpected success of its film adaptation had little effect on the long-struggling resort—in 1986, a year before the film was released, Grossinger’s ended its 70 year legacy.

The story of Grossinger’s is, at its root, an American story. The Grossingers were Austrian immigrants, who after some early years of struggle in New York City, and a failed farming venture, opened a small farmhouse to boarders in 1914, without plumbing or electricity. They quickly gained a reputation for their exceptional hospitality and incredible kosher cooking and outgrew the ramshackle farmhouse, purchasing the property that the resort still occupies today.

Grossinger’s rise to prominence is largely attributed to the couple’s daughter Jennie, who worked there as a hostess in its early years. Later, Jennie’s legendary leadership would transform the resort from its humble beginnings to a massive 35-building complex (with its own zip code and airstrip), attracting over 150,000 guests a year, and establishing a new type of travel destination that renounced the quiet charms of country living for a fast-paced, action-packed social experience that met the expectations of its sophisticated New York clientele.

Remnants of an attempt to burn down the Jennie G.

Every sport of leisure had its own arena, with state of the art facilities for handball, tennis, skiing, ice skating, barrel jumping, and tobogganing, along with a championship golf course. In 1952, the resort earned a place in history by being the first to use artificial snow. Its famous training establishment for boxers hosted seven world champions. Its stages launched the careers of countless well-known singers and comedians. In its day spas and beauty salons, ballrooms and auditoriums, guests were offered a level of luxury that even the wealthiest individuals couldn’t enjoy at home, earning Grossinger’s the nickname, “Waldorf in the Catskills.”

A daily missive called The Tattler identified notable guests and the business that made their respective fortunes. Weekly tabloids published on the grounds boasted the presence of celebrity athletes and entertainers. But for all the emphasis on earthly pleasures and material wealth, Jennie G. ensured that the Grossinger’s experience was warm and personal, always treating guests like one of the family, even when visitors reached well over 1,000 per week.

By the late sixties, the Grossinger’s model had started to fall out of favor as cheap air travel to tourist destinations around the world became readily available to a new generation. After the property was abandoned, several renovation attempts were aborted by a string of investors. Widespread demolition has greatly diminished the sprawl of the original resort, but several of the largest buildings remain. Most have been stripped of any vestige of opulence, and some structures are barely standing; no more so than the former Joy Cottage, whose floors might not withstand the footfalls of a field mouse.

Artifacts from the hotel’s glory days are few and far between, but Grossinger’s most recent batch of visitors has been quick to leave its mark. In a haunting hotel filled with empty rooms, some scenes are startlingly arranged, with collected mementos photogenically poised in the pursuit of a compelling shot. Despite these attempts to prettify Grossinger’s decline, the grounds retain an air of savage dilapidation, and an utter submission to nature.

An indoor swimming pool is Grossinger’s most enduring spectacle, and has become a favorite location of urban explorers near and far. Radiance remains in its terra-cotta tiles and its well-preserved space age light fixtures. Its dimensions continue to impress, as do the postcard views through its towering glass walls, all miraculously intact. It’s growth, not decay, that makes this pool so picturesque—the years have transformed this neglected natatorium into a flourishing greenhouse. Ferns prosper from a moss-caked poolside, unhindered by the tread of carefree vacationers, urged by a ceiling that constantly drips. Year-round scents of summer have bowed to a kind of perpetual spring, with the reek of chlorine and suntan lotion replaced by the heady odor of moss and mildew—it’s dank, green, and vibrantly alive.

Meanwhile, areas across the region that once relied on a thriving tourism industry have fallen into depression or emptied out. The Catskills is attempting to rebrand, updating its image and holding online contests to determine a new slogan. The winner? The Catskills, Always in Season.

Though it remains to be seen whether the coming seasons will bring new visitors, there’s no doubt they’re serving to erase the region’s outmoded reputation. With each passing year, in ruined hotels across the Catskills, the physical remnants of lost vacations dwindle. Indoors, snowdrifts weigh on aching floors; leaf litter collects to harbor the damp or fuel the fire. Vines claim what the rain leaves behind, compelling the constant progress of decay. Scattered in photo albums, hidden in bottom drawers, excerpted from yellowing newsprint, the memories will follow, clearing the way for new journeys. Before it’s forgotten, here’s one more look inside the celebrated resort.

This catwalk ensured a comfortable commute from your suite at the Paul G. to the indoor pool year-round.

A pitch-black beauty salon lit with the aid of a flashlight.

The ruined entrance to the hotel spa.

Office on the bottom floor of the Jennie G. Hotel.

The best preserved room, with two murphy beds, and a carpet of moss.

In most rooms, peeling wallpaper was all that remained.

The ground floor of the management office, now on the verge of collapse.

Hotel records neatly arranged on a mattress, by a photographer, no doubt.

In Gowanus’ Batcave, Broken Teenage Dreams Live on

Not long ago, a pack of teenage runaways lived the dream in Gowanus’ infamous Batcave, shacking up rent-free in an abandoned MTA powerhouse on the shore of the notoriously toxic Gowanus Canal. Out of the grime, in back rooms and crooked halls, the artifacts of this sizable squatter settlement remain to enlighten, amuse, and unnerve the intrepid few that enter the disreputable interior.

The old Central Power Station of the Brooklyn Rapid Transit Company was built in 1896 to serve a rapidly expanding subway system in the outer boroughs, positioned on the banks of the Gowanus Canal to ensure an efficient intake of coal to power an arsenal of 32 boilers and eight 4,000 horsepower steam-driven generators. The plant’s technology couldn’t keep up with the times, and after a brief second life as a paper recycling plant, the powerhouse was abandoned. Today, it’s more commonly known as the “Batcave,” supposedly named for the creatures that once congregated in its broken-down ceiling.

In the early 2000s, a colony of homeless young people settled inside the building, establishing a thriving, peaceable community. At onset, the squat held a positive reputation, kept under the watchful eye of a few individuals who ensured hard drugs and detrimental criminal activities were kept out. After a drunken rooftop incident, authorities were notified and made their first attempt to evict the punk-rock squatters, leaving the colony without its guardians.

Over the next two years, heroin use and overdose grew rampant, and a wave of brutality overwhelmed the Batcave. Drug-induced violence culminated in a series of nightmarish events; one homeless man was thrown from a window, another overdosed and was left on the street for law enforcement to find. Frightened community members saw to it that the Batcave colony was ousted indefinitely in 2006.

The residents are long gone, but most of their humble furnishings remain. Some living quarters, fashioned in old corner offices of the power plant, are generously sized, complete with beds, bookshelves, and lounge chairs. Others are no larger than a closet; album covers, skulls and superheroes, and a general state of chaos are prominent features of these impromptu bedrooms.

Prized possessions—a VHS copy of the Nightmare Before Christmas, a dogeared paperback edition of Hamlet—molder in the damp with shampoo bottles, plastic toys, and stockpiles of hypodermic needles. Stuffed animals are the most abundant, and telling artifacts. Once treasured, these hulking teddy bears, leather-clad Elmo dolls, and freaky Fisher-Price robots lie mired in filth, decapitated or gutted and hung from strings.

While large-scale pieces by notable graffiti artists dominate the Batcave’s main hall, the more intriguing artworks can be found on the bedroom walls. Always obscene, typically humorous, and occasionally clever, these amateur scrawls portray a community of fun-loving, hard-living, creative youth, although some inscriptions tend toward the dark and morbid, pointing to a deep resentment for society and obsessions with dying and suicide.

It’s no wonder so many lost souls found solace here—just look up. The Batcave’s eye-popping top floor certainly feels like a sanctuary. Light rain filters down from a collapsed ceiling, atomized to a sweeping mist. In a permanent puddle, arched reflections of the clerestory windows tremble. Pleated ceiling panels once muffled the hum and hiss of a mammoth industrial undertaking, but their effect is more visual now. Interweaving supports shimmer like the facets of a diamond as you move through the space—it’s a crustpunk kaleidoscope that constitutes one of the most spectacular abandoned sights in New York City.

For all the atmosphere of grime and decay, the Batcave gives an impression of a living space that, though not well kept, was certainly well loved. It isn’t difficult to imagine a time when this damp industrial shell was filled with warmth and welcome, or to imagine its occupants, in those first idyllic months, brimming with a sense of ownership and control, invulnerable to the pressures of parents and policemen.

The fate of the Batcave lies in the balance of Gowanus’ contentious transition from industrial wasteland to trendy residential neighborhood. Numerous plans have emerged for the development of the property, but the canal’s recent Superfund designation and an uncertain future for the game-changing Whole Foods development across the street has deterred potential investors from shelling out the millions necessary to renovate the structure and rehabilitate its environmentally hazardous grounds. Through an overgrown lot in the height of Spring, the dilapidated redbrick facade remains a sight to behold, concealing a sordid wonderland within, marking the spot where a youthful dream lived, and died.

-Will Ellis

UPDATE Nov 23, 2012: The Batcave property sold for $7 million to philanthropist Joshua Rechnitz. The building will be saved, and renovated into art studios and exhibition space. Read the New York Times article here.

Some rooms are relatively undisturbed. Couldn’t resist lighting this candle holder, fashioned out of a beer can.

A neighboring storage facility reflects its gawdy plastic siding into a Batcave nook, accenting some interiors with splashes of orange and blue.

Inside Creedmoor State Hospital’s Building 25

The first glimpse of Building 25’s fourth floor from the central stairwell. That’s not gravel.

In Queens Village, mere inches of brick and mortar separate the world we know from one of the strangest places in the city. Once a haven for New York’s cast-out mentally ill, Creedmoor Psychiatric Center’s Building 25 has undergone something of a transformation over its 40 years of neglect.

Creedmoor was founded in 1912 as the Farm Colony of Brooklyn State Hospital, one of hundreds of similar psychiatric wards established at the turn of the century to house and rehabilitate those who were ill equipped to function on their own. Rejected by mainstream society, hundreds of thousands of mentally disturbed individuals, many afflicted with psychosis and schizophrenia, were transferred from urban centers across the country to outlying pastoral areas where fresh air, closeness to nature, and the healing power of work was thought to be their best bet for rehabilitation.

As the 20th century progressed, asylums across the country became overrun with patients, and many institutions became desperately understaffed and dangerously underfunded. Living conditions at some psychiatric wards grew dire—patient abuse and neglect was not uncommon. Creedmoor State Hospital was habitually under scrutiny during this period, beginning in the 1940s with an outbreak of dysentery that resulted from unsanitary living conditions in the wards.

The hospital had spiraled completely out of control by 1974 when the state ordered an inquiry into an outbreak of crime on the Creedmoor campus. Within 20 months, three rapes were reported, 22 assaults, 52 fires, 130 burglaries, six instances of suicide, a shooting, a riot, and an attempted murder, prompting an investigation into all downstate mental hospitals. As late as 1984, the violent ward of Creedmoor Psychiatric Center was rocked with scandal following the death of a patient, who had been struck in the throat by a staff member while restrained in a straitjacket.

In the late 20th Century, the development of antipsychotic medications and new standards of treatment for the mentally ill accelerated a trend toward deinstitutionalization. A series of dramatic budget cuts and dwindling patient populations led to the closing of farm colonies across the United States, and a marked decline at Creedmoor. The campus continues to operate today, housing only a few hundred patients and providing outpatient services, leaving its turbulent past behind. Many of the buildings have been sold off to new tenants. Others, like Building 25, lie fallow.

The building was an active ward until some time in the 1970s, and retains many mementos from its days as a residence and treatment center for the mentally ill. With peeling paint, dusty furniture, and dark corridors, the lower floors are typical of a long-abandoned hospital, but upstairs, the effect of time has taken a grotesque turn.

The smell alone is enough to drive anyone to the verge of madness, but the visual is even more appalling. For 40 years, generations of pigeons have defecated on the fourth floor of Building 25, far removed from their dim-witted dealings with the human world, assembling a monument all their own. Guano accumulates in grey mounds under popular roosts, with the tallest columns reaching several feet in height. Like the myriad formations of a cavern, Buiding 25’s guano stalagmites are a work in progress—pigeons roost at every turn, and they’re awfully dubious of outsiders. Violent outbursts of flight punctuate an otherworldly soundscape of low, rumbling coos. The filth acts as an acoustic insulator, making every movement impossibly close.

These dropping formations formed under the pipes of a sprinkler system the birds frequented. (Prints Available)

Two levels down and a world away from the top floor, a kitchen is filled with years’ worth of garbage intersected by narrow pathways. A living room, kept relatively tidy, features a sitting area with an array of chairs, including a homemade toilet. Loosely organized objects litter every surface—toiletries, clothing, hundreds of dead D batteries. Some of the belongings looked as if they hadn’t been touched for decades, but a newspaper dated to only a few weeks before confirmed my suspicion that someone was still living here.

I found him snoozing peacefully in a light-filled dayroom, surrounded by a series of patient murals. Once painted over, images of faraway lands, country gardens, and the Holy Mother are coming to light again as time peels back the layers. The image was surprising, unforgettably human, and imprudent to photograph. Declining to introduce myself, I passed once more through the dark, decaying halls of Building 25, leaving its charms, horrors, and mysteries for the birds. Back on solid ground, its impression wouldn’t fade for months—Building 25 has a way of recurring in dreams…

Furniture stacked in a cafeteria on Building 25’s third floor.

These chairs are popular with urban explorers, one went as far as covering the upholstery with fake blood.

Metallic sheets are bolted to this bathroom wall in lieu of mirrors, which patients could use as a weapon.

A tiny toy collection arranged on a windowsill. (Prints Available)

An uninviting hallway on Creedmoor’s fourth floor.

This bathroom held the largest volume of fecal matter. (Prints Available)

An incongruous Virgin emerges from an infested day room. (Prints Available)