AbandonedNYC

Ruins

The Sea View Children’s Hospital

Forested views from a lower floor day room at Sea View Children’s Hospital.

At the turn of the twentieth century, tuberculosis was the second leading cause of death in the city and a major world health concern known to disproportionately affect the urban poor. In New York City, two-thirds of the 30,000 afflicted were dependent on city agencies for treatment. Growing concern from charitable organizations spurred the establishment of New York’s first public hospital designed exclusively to treat tuberculosis, care for the “sick, poor, and friendless,” and keep the epidemic under some measure of control by isolating sufferers from general hospitals. If you were diagnosed with tuberculosis in the early 1900s, your prognosis was grim. Lacking a cure, the only treatments thought to ease symptoms were fresh air, rest, sunshine, and good nutrition. A pleasant view was also considered essential for staving off depression. For this reason, hospital planners settled on a privately owned 25-acre hilltop parcel in rural Staten Island called “Ocean View,” just across from the already established New York City Farm Colony.

The plot was surrounded by a vast expanse of forested land (known as the Greenbelt today) which enabled the hospital grounds to expand as necessary. When Sea View Hospital was dedicated on November 12, 1913, the New York Times called it “the largest and finest hospital ever built for the care and treatment of those who suffer from tuberculosis.” The Commissioner of Public Charities claimed it was “a magnificent institution that is vast, ingenious, practical, convenient, sanitary, and beautiful, the greatest hospital ever planned in the world wide fight against the “white plague.” Though the new facilities effectively eased the suffering of tuberculosis patients and provided housing for the poor, little could be done to actually save lives in the long term. Most eventually succumbed to the disease.

Saplings take root in a light-filled solarium on the top floor. (Prints Available)

Two window fixtures had vanished, offering an unobstructed view of the surrounding woodlands.

Doorway into an open-air pavilion.

Hospital beds, cribs, and equipment left behind in a day room on a lower floor. (Prints Available)

In 1943, the development of the antibiotic streptomycin at Rutgers University led to a series of breakthroughs in the treatment of tuberculosis over the next decade, and much of that research took place at Sea View Hospital. The enthusiasm over these dramatic developments is captured in a 1952 report by the Department of Hospitals: “Euphoria swept Seaview Hospital. Patients consigned to death at the hands of the White Plague celebrated a new lease on life by dancing in the halls.” The transition was swift. By 1961, Sea View’s pavilions were practically emptied as patients miraculously recovered as a result of the new therapies. Today, a long-term care facility operates in several of the buildings and some structures have been repurposed by community agencies and civic groups, but much of the Sea View Hospital campus lies abandoned.

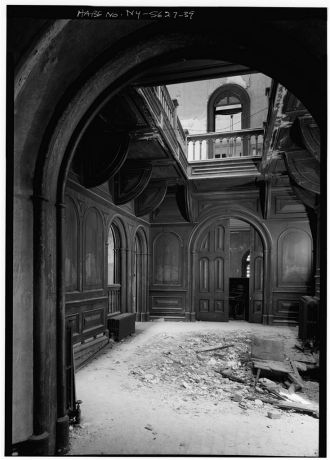

Past a fenced enclosure delineating the active section of the hospital, the grounds give way to the bramble-choked wilds of the Staten Island Greenbelt. The creepy ruins of the old women’s pavilions situated on the northern border are a popular detour on hikes from the neighboring boy scout camp. To the east lies the imposing Children’s Hospital, completed in 1938 and abandoned in 1974. Its spacious, window-lined solariums are typical of earlier Sea View wards, flanked on either side by open-air porches which were occupied by recovering patients 24 hours a day during the height of the epidemic. In an otherwise clinical Landmarks Preservation Commission report published in 1985, the researcher notes that “the building rises from a deep slope… Wooded surroundings, particularly dense to the east and south of the building, enhance the sense of isolation.” The view he’s describing is indeed one of New York City’s most surreal (pictured below in 2012).

The ominous Children’s Hospital, seen from a hilltop on the grounds of Sea View Hospital.

Reuse of the structure seems extremely unlikely given the large number of abandoned buildings within the active hospital complex that would make better candidates for restoration. Area conservationists are fighting to keep the surrounding woodlands protected from developers by making it a permanent part of the Greenbelt network of natural areas, and the building itself is nominally protected from demolition as part of Sea View Hospital’s historic district designation. That doesn’t mean that the building won’t serve a purpose as it continues to crumble. As I’ve mentioned in previous posts, Staten Island teenagers have a long history of voraciously exploring (and vandalizing) their local ruins. With the renovation of the Willowbrook State School in the 1990s, the later demolition of the Staten Island Monastery, and the impending restoration of the New York City Farm Colony, the isolated, under-the-radar Children’s Hospital may be next in line as the site of that requisite rite of passage. Only time will tell.

There’s little to suggest the building was used exclusively as a children’s hospital in its last years of operation.

Even the restrooms had windows for observation.

Drifts of plaster pile up on a table outside the darkroom.

The upright piano, an abandoned hospital staple.

“Dixie Cup for Dentures.” The name says it all.

A storage room in the attic had been pillaged.

A steep staircase led to the upper reaches of the utility floors.

Lowers floors were boarded up, which always allows for the eeriest light. (Prints Available)

The last room I came to was the most surprising–a boarded-up dayroom piled several feet high with hospital records.

IN OTHER NEWS… my friend Oriana Leckert‘s book “Brooklyn Spaces” is out this week. We’re a bit like kindred spirits, Oriana and I, but she goes more for the crowded, lively, and creative than the empty, eerie, and decrepit. The (50!) places profiled in the book show the authentic, human side of the global phenomenon that is “Brooklyn cool,” highlighting the heartfelt endeavors of a wave of culture makers that migrated to the borough for cheap rent and fashioned a network of bustling performance venues, art enclaves, and meeting places out of Brooklyn’s post-industrial landscape. Her obvious passion for offbeat museums, community gardens, communal living spaces, and out-there artist residencies is beyond infectious. Do yourself a favor and pick up a copy! And head to what I’m sure will be a raucous, sweaty launch party on May 30th.

IN OTHER NEWS… my friend Oriana Leckert‘s book “Brooklyn Spaces” is out this week. We’re a bit like kindred spirits, Oriana and I, but she goes more for the crowded, lively, and creative than the empty, eerie, and decrepit. The (50!) places profiled in the book show the authentic, human side of the global phenomenon that is “Brooklyn cool,” highlighting the heartfelt endeavors of a wave of culture makers that migrated to the borough for cheap rent and fashioned a network of bustling performance venues, art enclaves, and meeting places out of Brooklyn’s post-industrial landscape. Her obvious passion for offbeat museums, community gardens, communal living spaces, and out-there artist residencies is beyond infectious. Do yourself a favor and pick up a copy! And head to what I’m sure will be a raucous, sweaty launch party on May 30th.

Dredging the Archives + May 7th Library Lecture

The spooky Walloomsac Inn in Benington, VT is actually occupied as a private residence.

On Thursday, May 7th at 6:30 PM I’ll be presenting at the Mid-Manhattan Branch of the New York Public Library as part of their Author @ the Library series. This will be the last book talk I’m giving for a while, so if you’ve missed out on past events and would like to attend, now is the time. The best part is it’s totally free, open to the public, and there’s no need to register or buy a ticket. Head here for more info.

Since its release at the end of January, the book has gotten a great response, particularly on the world wide web. For the highlights, check out these bits in The New York Times, Wired, Complex, and Slate, who toured the Jumping Jack Pump House with me and captured it on video back in March.

I have some exciting posts in the works for you, but for now I wanted to share some images from the archive that haven’t been shown here before–places that didn’t warrant a full post for one reason or another, often because I couldn’t get inside, didn’t have time to poke around, or there just wasn’t a lot to see. Some of them are quite interesting nonetheless. Enjoy!

Sea View Hospital, Staten Island.

These mammoth LNG storage tanks in Rossville, SI were abandoned immediately after construction.

Ghost motel near Yosemite National Park.

San Francisco’s Fort Point. (not abandoned)

An abandoned house in Queens, now demolished.

A well-preserved surgeon’s residence at the Brooklyn Navy Yard Hospital.

An abandoned carriage house in Newport, RI locals call “the Bells.”

Murder in Mariner’s Marsh

Mariner’s Marsh, on Staten Island’s North Shore.

At a bend in Staten Island’s North Shore where the Arthur Kill gives way to the Kill van Kull, there’s a strange, desolate landscape that’s equal parts industrial wasteland and pristine wilderness. Here, an array of factories and freight lines are enveloped by a network of streams, swamps, ponds, and salt marshes, with place names like “Howland Hook” and “Old Place Creek” that wouldn’t feel out of place in a pirate story.

Mariner’s Marsh makes up 107 acres of the area, buffering a dense residential neighborhood from the sprawling New York Container Terminal with a wide expanse of green. Having endured a brief period of industrial use followed by 75 years of abandonment, the resulting wilderness is characterized by the vine-covered relics of factories that thrived on the spot 100 years ago. Even the Parks Department’s official signage describes the landscape as “eerie.” But the text rightfully avoids its darkest chapter, when in 1976 the tragic final act of a forbidden teenage love affair played out among the ruins of Mariner’s Marsh.

A trail leads walkers under an old concrete structure.

The ruins date back to the early 20th century, when the land was occupied by the Milliken Brother’s Structural Iron Works. Later, the foundry was converted to Downey’s Shipyard, which manufactured war ships, among other vessels. The factories closed down in the 1940s and have sat abandoned to this day. Wood components of the buildings have completely rotted away, but concrete pylons, pits, and passages remain. As the buildings deteriorated, the landscape transformed. Today, the former shipyard’s ten man-made basins function as reedy freshwater ponds. Elsewhere, the topography varies from pine and poplar forests to vine-gnarled swamps where wildlife and rare plants thrive.

A weathered birdwatching blind.

The requisite creepy doll head.

Mariner’s Marsh was acquired by the Parks Department in 1997, but it’s been “closed to the public during environmental investigation” for nearly a decade. The investigation in question took place in 2006 under the direction of the EPA, which found that a small area of the park contained a high concentration of hazardous materials stemming from its industrial age. Though it appears that some work has been done on the spot, it’s not clear when the park will reopen. In the meantime, warning signs haven’t stopped neighbors and dedicated bird watchers from enjoying it. Trails are well-defined and the area is relatively free of garbage, despite the presence of some larger debris. The east side of Downey Pond is dotted with abandoned hot rods from another era.

One of the park’s many abandoned cars.

An overturned vehicle marooned in a swamp east of Downey Pond.

Long before Staten Island’s industrial boom, the Lenape Indians camped here to take advantage of the nearby wetlands, where shellfish were plentiful. Remnants of the wetlands are still visible across Forest Avenue in Arlington Marsh, which is home to some of the last stretches of healthy salt marsh in New York City. Acquiring it was a major coup for the Parks Department, which plans to keep the 55 acres wild. Here, ghostly remnants of long-forgotten piers and burned out vessels seem oddly in sync with the tidal rhythms of the natural world. At low tide, a boat graveyard comes to the surface in an adjacent cove, where native cordgrass and mussel beds take root in the old hulls of 19th century sailing ships.

An expanse of pilings that once supported massive factory docks.

Oyster beds in the hull of a long-abandoned ship.

Fragment of a sailboat at Arlington Marsh.

This post would’ve ended there if I hadn’t come upon a mention of the 1976 murder of Susan Jacobson in connection with the area. Though the scene of the crime is never referred to as Mariner’s Marsh, the description is unmistakable in a New York Times article published in 2011, which begins:

“The 16-year-old boy had settled on a plan on how to kill his girlfriend. There was a blighted section on the north shore of Staten Island called Port Ivory, overgrown coastline facing the industrial banks of New Jersey. The land was pocked with holes leading to small underground rooms, like bunkers.

This abandoned lot was the last thing a 14-year-old girl named Susan Jacobson ever saw as she climbed down into one of those holes with her boyfriend, Dempsey Hawkins, on May 15, 1976. “

Ruins of a system of rails that closely match a description of the murder site.

Included in the article is a scan of a handwritten letter from Hawkins to the reporter in which he details an idyllic romance with Jacobson that ends abruptly following an abortion. In the final paragraph, he goes on, “In came 1976 and the insanity and the whole painful mess I am about to relate succinctly simply because it’s disturbing. I strangled Susan and concealed her body in a metal barrel in a wooded area across from a Proctor and Gamble factory on Staten Island.”

Two years passed before her remains were discovered by a boy playing in the tunnels. He had assumed they were dog bones until a friend spotted Susan’s tennis shoes. Hawkins, now 55, was denied parole for the eighth time in 2012 despite a history of good behavior behind bars. Parole commissioners have repeatedly taken issue with what occurred immediately after the crime. On multiple occasions, Hawkins himself participated in search parties for the missing girl, knowing all the while precisely where the body was hidden.

Icicles stretch into the darkness of the tunnel as vines spiral toward the light.

An arched passageway near the scene of the crime.

Book-Related Events Coming Up:

Brooklyn Brainery, April 15th 8:30-10:00, $7(Sold Out)- Dead Horse Bay, May 2nd, @ 12:45 I’ll be leading a walking tour of one of my favorite places in NYC with Untapped Cities

- Mid-Manhattan Library, May 7th, 6:30-8:00 PM, Free!

Last Days of the Staten Island Farm Colony

Part of what makes abandoned buildings so captivating is that their existence is ephemeral, they cannot remain decayed and crumbling forever, and inevitably that means saying goodbye.

Admittedly, the Staten Island Farm Colony is not one of the most spectacular places I’ve seen, (the interiors have been completely destroyed by vandalism) but it remains the one place I’ve come back to more than any other. What’s always impressed me about it is its changeability. The place is reborn with every season, and I suppose that’s true of all abandoned buildings, but I’m always struck by it at the Farm Colony. In the height of summer, its jungle-like atmosphere lends it the look of a fallen Aztec empire, which is almost unrecognizable in the cooler months. It’s haunting in the fall when the fog rolls in, and desolate in the winter when ice and snow blanket the buildings inside and out. Through 40 years of abandonment, the Farm Colony is as ever-changing as the natural world that engulfs it, but it’s looking more and more definite that this historic district will be undergoing a final, permanent transformation in the days ahead.

Last month, the Landmarks Preservation Commission unanimously approved a proposal to bring 350 units of senior housing to the site, part of a large new development called “The Landmark Colony.” In the process, the institution is returning to its historic function as a home for the elderly after a four decade hiatus. (The place was essentially a geriatric hospital when it closed down in the 1970s, though it had been established in the mid 19th century as a refuge for the poor.) With five buildings saved and one kept as a stabilized ruin, the design will preserve much of the area’s architectural character. The remaining structures will be demolished and replaced with modern residential units, which is to be expected considering just how far gone some of these buildings are.

Several of the places I’ve photographed in the last few years have been set aside for renovation (The Domino Sugar Refinery, the Gowanus Batcave, and P.S. 186 to name a few.) The Smith Infirmary, the old Machpelah Cemetery office, and most troublingly, the Harlem Renaissance Ballroom have not been so lucky. It’s rare and encouraging when a structure is fortunate enough to get a second chance in this rapidly evolving city, but as positive as these changes are for their communities, a part of me still feels like something is lost. I know I’m not the only one who’ll miss the Farm Colony and its embattled ruins, which have become a popular spot for paintballers and Staten Island teenagers to pass the time.

Here’s a series of photos I’ve taken over the last year in sweltering heat, biting cold, snow, rain, and fog. Hopefully I make it back one last time before these ancient grounds are covered with fresh paint and brimming with active retirees year-round.

But a similar dormitory on the south side of the grounds will be stabilized and preserved as a ruin.

Trees silhouetted against the clouds, projected through a camera obscura on the ground floor of a residence hall.

The “Haunting” of Wyndclyffe Mansion

The Hudson River Valley is home to more than its share of formidable ruins, but few match the spooky appeal of Rhinebeck’s Wyndclyffe Mansion. Its beetle-browed exterior is blessed with that beguiling combination of gloom, ornamentation, and extreme old age that only the best haunted houses claim, and there’s no better time to witness them than late October, when autumn breezes send yellow leaves eddying through the hills and hollows of the old estate. It seems that the only thing this “haunted house” is missing is a good ghost story…

Much of what remains of the interior is far too unstable to access, this was taken from a window on the west side of the structure.

Murder, mayhem, and the supernatural don’t factor at all into the history of Wyndclyffe, but its past is compelling enough as it is. The manor was constructed in 1853 as the private country house of Elizabeth Schermerhorn Jones, who was a prominent member of an exceptionally wealthy New York family. Though palatial Hudson Valley estates were already in vogue among New York City’s ruling class, the magnificence of Wyndclyffe prompted neighboring aristocrats to throw even more money into their vacation homes so as not to be overshadowed by Elizabeth’s Rhinebeck abode. The house and the fury of construction it inspired is said to be the origin of the phrase, “keeping up with the Joneses.”

Elizabeth was the aunt of the great American author Edith Wharton, who is known for her keen, first-hand insight into the lives of America’s most privileged, which she brought to bear in classics like Ethan Frome, The House of Mirth, and The Age of Innocence, for which she won the Pulitzer Prize. (She’s also known for her ghost stories.) In her early youth, Edith would spend summers in the house, which was known by her as “Rhinecliff.” She portrayed it in less than laudatory terms in her late-career autobiography “A Backward Glance” (1934):

“The effect of terror produced by the house at Rhinecliff was no doubt due to what seemed to me its intolerable ugliness… I can still remember hating everything at Rhinecliff, which, as I saw, on rediscovering it some years later, was an expensive but dour specimen of Hudson River Gothic: and from the first I was obscurely conscious of a queer resemblance between the granitic exterior of Aunt Elizabeth and her grimly comfortable home, between her battlemented caps and the turrets of Rhinecliff.”

Many of the original architectural details are still visible in a collapsed section of the building, notice the wood detailing in the second floor parlor.

Her words bring to mind this passage from Shirley Jackson’s “The Haunting of Hill House” which describes the titular (fictional) structure:

“No human eye can isolate the unhappy coincidence of line and place which suggests evil in the face of a house, and yet somehow a maniac juxtaposition, a badly turned angle, some chance meeting of roof and sky, turned Hill House into a place of despair, more frightening because the face of Hill House seemed awake, with a watchfulness from the blank windows and a touch of glee in the eyebrow of a cornice. Almost any house…can catch up a beholder with a sense of fellowship; but a house arrogant and hating, never off guard, can only be evil.”

Here’s the same room pictured in the 1970s, with the floor already severely damaged by a leaky skylight.

The modern eye is likely to be much more merciful to the embattled Wyndclyffe, evil or no. Its beauty is readily apparent, and arguably enhanced, by the extent of decay it has suffered through 50 years of neglect. But how does a house as expensive, distinctive, and historically relevant as Wyndclyffe end up in such a state?

When Elizabeth passed away in 1876, Wyndclyffe was sold to a family who maintained the house into the 1920s, but the succession of owners that occupied the mansion through the Great Depression struggled to keep up with the costly repairs it required. In the 1970s, the house had already been abandoned for decades as the Hudson Valley’s status as a playground for the wealthy declined. At this point, the property was purchased and subdivided, which pared down the grounds of the estate from 80 acres to a paltry two and half. This action more than any other spelled doom for Wyndcliffe—notwithstanding the astronomical expense required to renovate a partially collapsed 160 year old mansion, the lack of land surrounding the structure has made it an extremely difficult sell to potential buyers. While many nearby estates have been renovated into thriving historic sites after a period of neglect, Wyndclyffe has struggled even to remain standing.

A glimmer of hope appeared in 2003 when a new owner cleared most of the trees and overgrowth from the grounds, erected a fence, and announced plans to save the mansion. But as is often the case, good intentions fade in the face of financial realities. Eleven years have come and gone and the meager improvements are difficult to discern—thick saplings, tangled thorns, and shrubbery completely envelop the structure once again, and the progress of decay marches on.

Numerous “No Trespassing” signs are posted around the property. State troopers are often summoned to the site when nearby homeowners alert them to suspicious activity.

Since Halloween is just around the corner, I’ll leave you with another eerie passage from Jackson’s “Haunting,” which is said by Stephen King (who should know) to be the best opening paragraph of any modern horror story. It deftly captures the uncanny appeal of empty buildings, and the persistent, however illogical, impression that a house continues to think, feel, and ruminate over its past long after it’s left behind by man.

“No live organism can continue for long to exist sanely under conditions of absolute reality; even larks and katydids are supposed, by some, to dream. Hill House, not sane, stood by itself against its hills, holding darkness within; it had stood so for eighty years and might stand for eighty more. Within, walls continued upright, bricks met neatly, floors were firm, and doors were sensibly shut: silence lay steadily against the wood and stone of Hill House, and whatever walked there, walked alone.”

Snooping in Storybook Castle

The entrance to Storybook Castle.

A deserted castle in the woods always has a few stories to tell. Maybe you’ve heard of the heart-shaped pools at Storybook that fill with blood on a full moon, or the Rapunzel-inspired succubus who hangs her hair to tempt gullible fishermen to their doom in the highest tower. Locals will tell you about the mad widow kept locked in a room with no doorknobs, who escaped on occasion to ride through town on horseback tossing gifts to children. (Supposedly, you can still find scratch marks where she clawed her way out.)

Most of these stories don’t hold water, of course, but the truth is nearly as strange. For starters, no one has ever lived in the castle.

The facts are few but generally accepted. Construction began in 1907 by a prominent New Yorker and heir to the builder of a famous canal. He transformed a nondescript wooden lodge that already stood on the property into a fanciful fairy tale castle modeled after a Scottish design, cutting corners with local river rocks on the facade but indulging in fine imported marble for the interior. Some say the castle was built out of love for his ailing wife, who suffered from mental illness. Unfortunately, the owner died in 1921 just before the structure was completed. Instead of moving into the romantic hideaway, his grieving widow was checked into a sanatorium shortly thereafter. The couple’s daughter and sole heir ran off to Europe with a new husband, leaving a caretaker to look after the unfinished castle.

The courtyard out back is periodically maintained, the lawn appeared to have been mowed recently.

In 1949, the property was purchased by the Prince Hall Grand Lodge of the Masonic Order, an African American group based in Manhattan. The original plan was to convert the castle to a masonic home for the elderly, but it was instead used for many years as a hunting and fishing resort. Later, the property became a summer camp for inner-city youth. As far as I can tell, the expansive grounds still serve this function today, though the castle itself has reportedly only been used to creep out campers over the years. There may be no more fertile ground for legends than a summer camp set in the vicinity of a derelict castle. Tales of glowing green eyes, apparitions in white, moving portraits, and self-slamming doors abound.

In 2005, the Prince Hall Masons and the Open Space Initiative announced an agreement to protect the castle and surrounding land, limiting future development and prohibiting residential subdivision. Unfortunately, nearly 10 years later, the castle is left completely vulnerable to vandals and exposed to the elements. Though the interior is remarkably well-preserved, several rooms are tagged up with uninspired graffiti. For this reason, I’ve chosen not to reveal the true name or location of the castle, be advised that the building is located on private property.

Click through the gallery to see the interior:

Wandering Fort Wadsworth

Battery Weed looms over a desolate shoreline in Fort Wadsworth, Staten Island.

At the easternmost tip of Staten Island, a natural promontory thrusts over the seething Narrows of the New York Harbor, formed by glaciers thousands of years ago. The site’s geography most recently made it a prime location for the Verrazano Bridge, but its history as a popular scenic overlook and strategic defense post dates back to the birth of the nation. The British had occupied the area during the Revolutionary War, and its first permanent structures were built by the state of New York in the early 1800s. These fortifications safeguarded the New York Harbor during the War of 1812, but were abandoned shortly thereafter. So began the familiar cycle of ruin and rebirth that characterizes the history of Fort Wadsworth.

By the mid-19th century, these early structures had fallen into an attractive state of decay. In a time when all of Staten Island held a romantic appeal as an escape from the burgeoning industrialism of New York City, Fort Wadsworth in particular was known for its dramatic terrain, sweeping views of the harbor, and evocative old buildings. Herman Melville described the scene in 1839:

“…on the right hand side of the Narrows as you go out, the land is quite high; and on top of a fine cliff is a great castle or fort, all in ruins, and with trees growing round it… It was a beautiful place, as I remembered it, and very wonderful and romantic, too…On the side away from the water was a green grove of trees, very thick and shady and through this grove, in a sort of twilight you came to an arch in the wall of the fort…and all at once you came out into an open space in the middle of the castle. And there you would see cows grazing…and sheep clambering among the mossy ruins…Yes, the fort was a beautiful, quiet, and charming spot. I should like to build a little cottage in the middle of it, and live there all my life.”

Under the Verazzano Bridge.

The “castle” was demolished to make way for new fortifications constructed as part of the Third System of American coastal defense, known as Battery Weed and Fort Thompkins today. The batteries remain the fort’s most impressive and unifying structures, but they too were deemed obsolete as early as the 1870s due to advances in weaponry, and were used for little more than storage by the 1890s. At the turn of the 20th century, Fort Wadsworth entered yet another phase of military construction under the Endicott Board, when the United States made a nationwide effort to rethink and rebuild its antiquated coastal defenses. Like its predecessors, the Endicott batteries never saw combat, and were essentially abandoned after World War I.

Inside a powder room of Battery Catlin.

A squatter’s unmade bed in the back of the structure.

Though Fort Wadsworth was occupied by the military in various capacities until 1995, its defense structures went unused for most of the 20th century. By the 1980s, woods and invasive vines had covered areas that were once open fields, and Battery Weed was living up to its name, overtaken by mature trees and overgrowth. Since Fort Wadsworth was incorporated into the Gateway National Recreation Area in 1995, its major Third System forts (Battery Weed and Fort Thompkins) have been well maintained and properly secured, and upland housing and support buildings have been occupied by the Coast Guard, Army Reserve, and Park Police. But the headlands still retain an air of abandonment, due in large part to the condition of the Endicott Batteries, which remain off-limits to the public.

Over five of these batteries are scattered across the grounds, all in various states of disrepair.

The Endicott Batteries are filled with narrow, windowless rooms, tomblike hollows, and underground shafts.

Their military blandness stands out in contrast to the grace and grandeur of the fort’s earlier structures deemed worthy of preservation.

Layers of history peel back like an onion at Fort Wadsworth, as evidenced by a new discovery just unearthed by Hurricane Sandy. The storm caused a section of a cliff to collapse, downing several large trees and exposing the entrance to a previously unknown battery. Its vaulted granite construction places it firmly in the Third System, which means it was built around the time of the Civil War. Very little is known about the structure, except that it’s the only one of its kind at Fort Wadsworth. My best guess traces its partial construction to the 1870s, when Congress left many casemated fortifications unfinished by refusing to grant additional funding.

A previously unknown granite battery, possibly dating back to the Civil War, was unearthed by Hurricane Sandy.

Large mounds of soil block the interior of the battery from view.

They’d been sifted through ventilation shafts in the ceiling over decades of burial.

Over the mound, the vaulted structure leads deeper into the ground.

To my disappointment, the next room came to a dead end, and to my horror, it was crawling with hundreds of cave crickets. These blind half spider/half cricket monstrosities pass their time in the darkest, dampest, most inhospitable environments, and are known for devouring their own legs when they’re hungry. They give perspective to the level of isolation of this chamber, which likely stood underground for over a century.

What other mysteries still lie buried in the lunging cliffs of Fort Wadsworth, or the depths of this forgotten battery? The dirt may well conceal deeper rooms and darker discoveries…

Cave crickets in the deepest room of the forgotten battery.

Special thanks to Johnnie for the tip! Get in touch if you know of a historic, abandoned, or mysterious location in the five boroughs that’s worth exploring.

Beyond NYC: Ghost Hunting in the “Bloody Pit”

Imagine a picture-perfect October afternoon—white steeples set against a crisp blue sky, apples to be picked, pumpkins to be carved, colonial headstones moldering beneath a gaudy display of fall foliage…

Only in New England is the essence of autumn so vividly arrayed, no more so than the Berkshires of western Massachusetts. The pastoral region was revered among literary luminaries of the 19th century—it’s rumored that Melville first envisioned his white whale in the wintry outline of Mount Greylock—but it’s also a wellspring of inspiration for local storytellers. The Berkshire hills are laced with legends and more than their fair share of ghost stories, so I got out of town to explore this mysterious region and hopefully encounter a few ghosts, just in time for Halloween.

The Old Coot is usually sighted in January; so I settled for this reenactment.

My first stop was the Bellows Pipe Trail on Mount Greylock, known to be haunted by a ghost called the “Old Coot.” This unfortunate soul went by the name of William Saunders in life and earned his living as a farmer before being called away to fight for the Union in 1861. His wife Belle assumed the worst when the letters stopped coming after receiving word that her husband had been injured in battle. But Bill Saunders had survived, only to return home and find Belle remarried. He retreated to a ramshackle cabin on Mount Greylock, where he lived out the rest of his days as a hermit, occasionally working on nearby farms. One day, a group of hunters entered his shack and came across his lifeless body. They were the first to describe a sighting of the Old Coot’s spirit fleeing up the mountain, but he’s haunted the trail ever since.

Madame Sherri failed to make an appearance on her old staircase. (Click here for a less ghostly image)

Madame Sherri

On the outskirts of Brattleboro, rumors about one eccentric local are still raising eyebrows more than fifty years after her death. Madame Sherri was a well-known costume designer in jazz-age New York City whose designs were featured in some of the most successful theatrical productions of the day. After her husband died of “general paralysis due to insanity,” Madame Sherri retreated to an elaborate summer home in the Berkshires, where she was known to throw lavish and unsavory parties for her well-heeled guests, often gallivanting about town in nothing but a fur coat. Gradually, her fortune was depleted and the dwelling was abandoned in 1946. Late in life, she became a ward of the state and died penniless in a home for the aged. Her “castle” burned to the ground on October 18, 1962, but its dramatic granite staircase remains to this day. Sounds of revelry have been heard emanating from the ruins of the old estate, where the apparition of an extravagantly dressed woman has often been spotted ascending the staircase.

Parked at the base of Mount Greylock.

If Madame Sherri’s Forest and the Old Coot’s trail don’t give you goosebumps, this next one might. To get there, you have to go down—way down—into the Hoosic River Valley to the bedrock of the Hoosac Mountains in North Adams, MA. Turn off on an unnamed dirt road, park at the train tracks, take a short hike, and you’ll come face to face with one of the most haunted places in New England. How far would you be willing to venture into the “Bloody Pit?”

The town of North Adams appears from a hillside en route from Mt. Greylock.

In 1819, a route was proposed to transfer goods from Boston to the west, and the Hoosac Range was quickly identified as the project’s biggest obstacle. Construction began in 1855 on the 5-mile Hoosac Tunnel, but the dig was plagued with problems from the beginning. When steam-driven boring machines, hand drills, and gunpowder proved too slow, builders turned to new, untried methods, namely nitroglycerine, an extremely powerful and unstable explosive. The tunnel claimed close to 200 human lives over the course of its 20-year construction, earning the nickname “The Bloody Pit.” The work was merciless, but precise—when the two ends met in the middle, the alignment was off by only one half inch.

An abandoned pumphouse sits beside a waterfall in the woods near the railroad tracks.

On March 20, 1865, Ned Brinkman and Kelly Nash were buried alive when a foreman named Ringo Kelly accidentally set off a blast of dynamite. Fearing retaliation, Ringo disappeared, but one year later, he was found strangled at the site of the accident, two miles into the tunnel. No one witnessed the crime, but most men agreed—the ghosts of Ned and Kelly had slaked their revenge.

The entrance to the Hoosac Tunnel opens up from around a bend in the tracks.

The most costly accident in the tunnel’s history occurred the following year on October 17th, halfway through the digging of a 1,000-foot vertical aperture called the Central Shaft which was designed to relieve the buildup of exhaust in the tunnel. Thirteen men were working 538 feet deep when a naphtha lamp ignited the hoist building above them, sending flaming debris and sharpened drill bits raining down. The explosion destroyed the shaft’s pumping system and the pit soon started filling up with water. When workers recovered the bodies several months later, they discovered that several of the men had survived long enough to construct a raft in a desperate attempt to escape the rising waters. The accident halted construction for the better part of a year.

The entrance to the Hoosac Tunnel

When work resumed, laborers reported hearing a man’s voice cry out in agony, and many walked off the job, claiming the tunnel was cursed. Through the 19th century, local newspapers reported headless blue apparitions, ghostly workmen that left no footprints in the snow, and disappearing hunters in and around the Bloody Pit. As recently as 1974, a man who set out to walk the length of the tunnel was never heard from again.

Staring down the black maw of the Hoosac Tunnel.

In spite of these tales, I found myself standing at the entrance to the West Portal, where a single bat sprung out of the darkness, setting the tone for what would prove to be a rather unsettling experience. The tunnel is undeniably creepy, lined with old crumbling bricks, half flooded with gray water, and coated with almost two centuries of soot and grime. It didn’t help that I was visiting on October 17th, the anniversary of its grisliest accident…

Sure enough, the moment I stepped across the threshold, my camera started taking pictures by itself. (Granted, it’s been having issues lately, but the timing and severity was uncanny.) The whole time I was in the tunnel, I was unable to gain control of the shutter, and had to resort to setting up a shot and waiting for the “unseen forces” to take each picture. It beats me why a ghost would choose to fiddle with my camera rather than, say, making the walls bleed, but the entire encounter left this skeptic scratching his head. Were these the spirits of the Hoosac Tunnel?

* * *

Back at the campsite, with the fire extinguished, I settled in for a fitful sleep on the hard ground, unable to shake that uneasy feeling. That night, the falling leaves outside the tent sounded just like footsteps. When the wind blew, the whole forest sounded like a crowd of ghosts walking. It was exactly the kind of night I had hoped to pass in the Berkshire hills, a chance to experience the other side of the season, beyond the spiced cider and the pumpkin lattes, far older than the covered bridges that cross the languid Hoosic River, that ancient date that marks the beginning of the dark half of the year, when the boundary between the living and the dead is at its thinnest point.

As far as I dared to go in the haunted Hoosac Tunnel.

A bit of Halloween spirit displayed outside the Bellows Pipe Trail.

Ruins of the ’64 New York World’s Fair

The empty observation towers of the New York Pavilion hover over Flushing Meadows-Corona Park.

In Flushing Meadows-Corona Park, the oddball ruins of the “Tent of Tomorrow” are fading into yesterday. This land had been home to the Corona Ash Dumps—immortalized as the “valley of ashes” in the Great Gatsby—until master builder Robert Moses set out to transform the area by selecting it as the site of the 1939 New York World’s Fair. While the overall design of the park was laid out for the ’39 event, its most evident landmarks date back to the ’64 exhibition. The Space Age design of the New York Pavilion was intended to inspire visitors with the promise of the future, but today it serves to firmly plant the structure in the context of the 1960s.

The New York State Pavilion in its youth.

The tallest tower was the highest point in the fair at 226 feet.

Concieved by New York businessmen and funded by private financing, the 1964-65 New York World’s Fair was once again headed by Robert Moses, who saw the project as an opportunity to complete his vision for Flushing Meadows Park. In order to make the fair financially feasible, organizers charged rent to exhibitors and ran the attraction for two years, ignoring the regulations of the worldwide authority on world’s fairs (the Bureau of International Expositions.) As a result, the BIE refused to sanction the fair and instructed its forty member nations not to participate, which included Canada, most European Nations, Australia, and the Soviet Union.

Faint remnants of bright yellow paint can still be spotted on the metal components of the structure.

The fair was dedicated to “Man’s Achievement on a Shrinking Globe in an Expanding Universe,” but the majority of exhibitors were American companies. Some of the most popular destinations included General Motors’ “Futurama” exhibit, Disney’s original “It’s A Small World” attraction, and a model panorama of New York City (which you can still visit at the Queens Museum of Art). Although over 51 million people attended the fair, the turnout was far less than expected. The project ended in financial failure, returning only 20 cents on the dollar to bond investors.

The observation decks were re-imagined as space ships in the original Men In Black film.

Most of the World’s Fair pavilions were temporary constructions that were demolished within six months of closing, but a few were deemed worthy of becoming permanent fixtures of the park. Once the centerpiece of the fair, the 12-story high stainless steel Unisphere has gone on to become a widely recognized symbol of Queens. Designed by notable modernist architect Philip Johnson, the nearby observation towers and the “Tent of Tomorrow” remain striking examples of the Space Age architecture the fair embraced. Unfortunately, they’ve sat empty for decades, and are starting to show their age. In the Tent of Tomorrow, space that once hosted live concerts and exciting demonstrations are occupied by stray cats and unsettling numbers of raccoons.

The Tent of Tomorrow once held the record as the largest cable suspension roof in the world.

The pavilion was reopened as the “Roller Round Skating Rink” in 1970, but roof tiles soon became unstable and the city ordered the attraction to close by 1974. Owing to their singular design, the structures have found their way into the background of many feature films, television shows, and music videos, including a memorable turn as a location and plot element for the original Men in Black. You can still make out the design of the pavilion’s main floor—modeled after a New York state highway map—in this late ’80s They Might Be Giants video.

The New York State Pavilion was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 2009, and a group of preservationists have helped clean up the exterior, restoring a bit of the original color scheme. As we near the 50th anniversary of the ’64 World’s Fair, here’s hoping something can be done to put these unique structures back to use.

A group of preservationists have restored the original paint job on the structure’s exterior.

Vines, and a not entirely incongruous robot head, have been affixed to this tower.

San Francisco’s Spooky Sutro Baths

Crumbling stairways at San Francisco’s Sutro Baths.

When the Sutro Baths first opened to the public in 1896, the west side of San Francisco was a vast region of all-but-unpopulated sand dunes. The sprawling natatorium was a pet project of Adolph Sutro, a wealthy entrepreneur and former mayor of San Francisco who became widely known as a populist over his illustrious career. Before constructing his magnificent bathhouse at Land’s End, he opened the grounds of his personal estate to all San Franciscans. Later, when transportation costs proved too high for many to reach his baths, he built a new railroad with a lower fare.

The Sutro Baths were the world’s largest indoor swimming establishment, with seven pools complete with high dives, slides, and trapezes, including one fresh water pond and 6 saltwater baths of varying temperatures with a combined capacity of 10,000 visitors. The water was sourced directly from the Pacific Ocean during high tide, and pumped during low tide at a rate of 6,000 gallons per minute. The monumental development also featured a 6,000-seat concert hall and a museum of curios from Sutro’s international travels.

The Sutro Baths in their glory days.

What remains of the Baths today.

The Baths’ popularity declined with the Great Depression and the facility was converted to an ice skating rink in an attempt to attract a new generation of visitors. Facing enormous maintenance costs, the Sutro Baths closed in the 1960s as plans were put in place for a residential development on the site. Soon after demolition began, a catastrophic fire broke out, bringing what remained of the glass-encased bathhouse to the ground. (There’s some suspicion that the fire was related to a hefty insurance policy on the structure, though it’s never been confirmed.)

The condo plans were scrapped and the concrete footprints of the Sutro Baths were left largely undisturbed. In 1973, the site was included in the Golden Gate National Recreation Area, and the ruins were opened to the public for exploration. This is not your typical park; as one sign warns, “people have been swept from the rocks and drowned.”

The highlight of any trip to the Sutro Baths is the cliffside tunnel. Through a pair of apertures, visitors can watch waves collide on the rocks below as the unlit corridor fills with briny mist and the booming sounds of the sea. In this spot, you might catch yourself believing vague rumors of hauntings that hang like a fog around the ruins of the Sutro Baths, or as some would have it, strange sightings of Lovecraftian demigods that lurk in its network of subterranean passages…

-Will Ellis

The cavern at Sutro Baths.

A misty opening reveals the teeming ocean below.

A portion of the property has been deemed too dangerous for the public…

…apparently for good reason.

This pool was freshly inundated with sea water.

Stunning views of the foggy Pacific from a clifftop lookout.

Purple flowers color an otherwise gloomy scene.