AbandonedNYC

new york

Time Traveling in the Children’s Ward: Rockland Psychiatric Center

Pink walls distinguish the girl’s ward of the former Rockland State Hospital children’s building.

Old buildings have many lives. Often the objects left behind in a modern ruin only reflect a place’s most recent iteration. But in Rockland County, one structure exists as a veritable nesting doll of time periods. Today, some areas of the abandoned Children’s Hospital at Rockland Psychiatric Center are unsettlingly modern, looking like a tornado swept through a present-day kindergarten classroom. But stepping from one room to the next can take you back another 10, 20, 30 years…

A coffee mug seems out of place in this heavily decayed section of the hospital.

The squat, maze-like ward was constructed in 1929 to house the youngest subset of Rockland State Hospital’s population. (The history of the institution and its notable bowling alley were outlined in a previous post.) Though it hasn’t been used to house mentally ill children since the 1960s and 70s, it continued to serve the needs of kids and families in recent decades. Beginning in the 1980s it was used as a day care center for children of RPC employees called “Kid’s Corner.” In 1998, sections of the building were used for a program called “Under the Weather,” which provided free care to moderately sick kids, enabling their parents to get back to work while their children recuperated. These valuable programs were abruptly closed by the Department of Mental Health in 2008 for budgetary reasons.

This section of the building was last used in the early 2000s as a day care center.

A Peanuts mural from the 90s or early 00s would have been in poor taste several decades earlier.

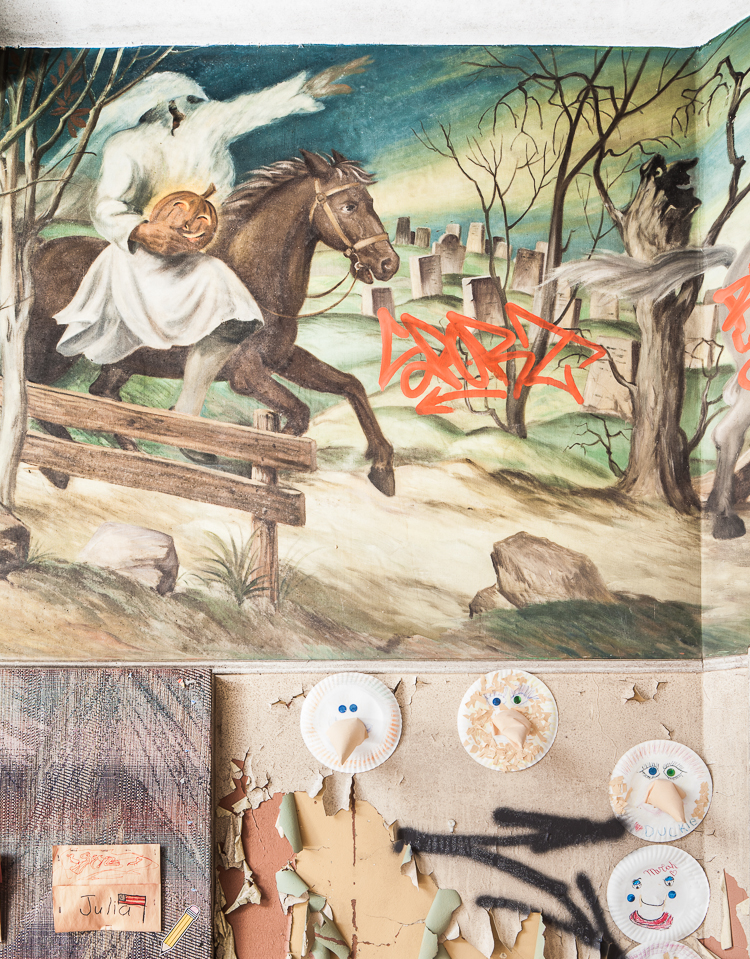

All of these developments can be traced through the hospital’s extensive collection of murals. They vary greatly in quality and subject matter, but all represent a concerted effort by founders and staff to brighten up the institutional halls over the years. The finest of them is a series of thoughtfully designed and obviously professional works depicting scenes from the tales of Washington Irving. These and a similar set depicting the four seasons were painted in the 1940s by the Works Progress Administration muralist Victor Pedrotti Trent. Much of the work is well-preserved, but some areas have suffered irreparable water damage. Years ago a study estimated that moving and restoring the paintings would cost $100,000, a prohibitive figure. Since then, there’s been little interest in preserving them.

In one section of the mural depicting classic stories by Washington Irving, Rip Van Winkle awakes from a long slumber.

Ichabod Crane flees from the Headless Horseman in this scene from “Sleepy Hollow.” Note the creepy face in the hollowed out tree.

Some sections of the mural are heavily damaged by water and temperature fluctuations.

Through the painted vestibule, beer bottle middens pile up in a relatively plain auditorium.

The building is the oldest of several structures on the campus that catered to children with psychiatric disorders. A modern children’s center is still in operation at Rockland Psych, and another built in the 1960s is currently being leased as a filming location for the hit Netflix show “Orange is the New Black,” standing in for the women’s prison depicted in the series. The 1929 hospital was slated for demolition years ago, but that doesn’t appear to be happening any time soon.

Though much of the building is crowded with modern-day kid stuff, some wings of the structure–namely the former boy’s ward–appear to have been walled off during the 80s and 90s. Those halls are largely empty, and the few artifacts left behind are far older and institutional in nature. I wonder if the youngsters at Kid’s Corner realized there was a children’s asylum ward preserved like a mosquito in amber just on the other side of their playroom…

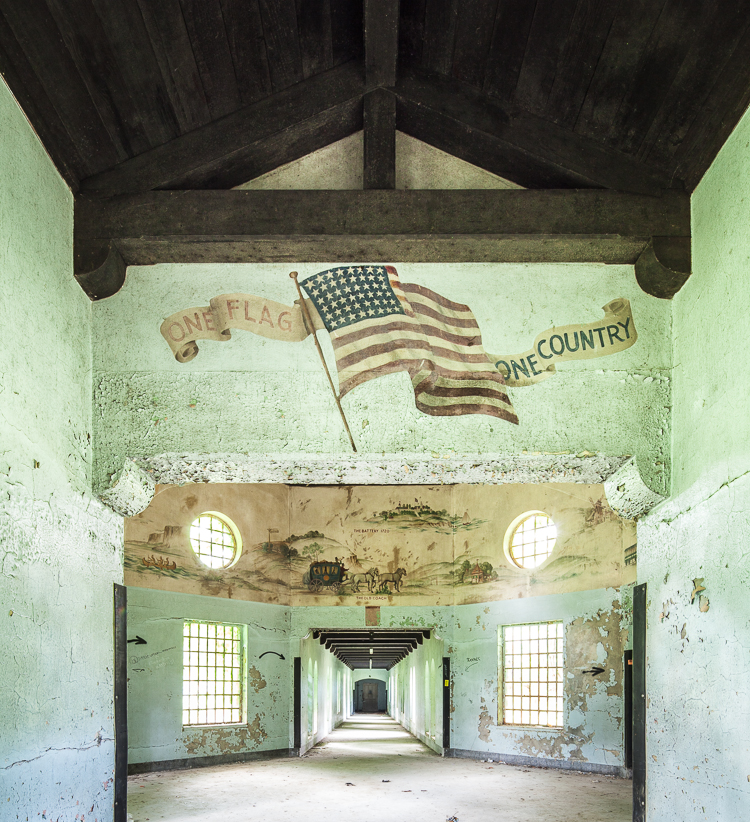

A mural with patriotic themes characterizes the boy’s wing of the structure.

Though not as impressive as the Trent murals, it offers a charming timeline of the development of New York City…

…beginning with the voyage of The Half Moon, a Dutch East India Company vessel.

A few relics from the state hospital era lie scattered around the halls, likely moved here for an urbex photo op.

Paper stars wither like autumn leaves over a doorway in the former boy’s ward.

IN OTHER NEWS… I’ve had a few spots open up on a tour of Dead Horse Bay I’ll be leading this weekend. It will take place Sunday, November 8th and we’ll be meeting at 10AM. It’s short notice, but I’d be happy to have a few more folks join in! Tickets available at this link.

ALSO… I’m excited to announce Abandoned NYC just went into its second printing! Thanks to all who helped me reach this milestone by ordering a book, showing up to events, and supporting the blog. To those who haven’t gotten their hands on a copy, get your signed first edition while supplies last!

Inside Rockland Psychiatric Center

An abandoned section of the former Rockland State Hospital, now known as Rockland Psychiatric Center.

In 1923, the New York state legislature passed a $50 million bond issue for the construction of new mental hospitals. After a disastrous fire at Ward’s Island in 1924, “where scores of mentally afflicted…were burned to death,” $11 million was set aside for a new campus designed specifically to relieve overcrowding at institutions in New York City. The town of Orangeburg, NY was chosen for its proximity to the five boroughs, picturesque surroundings, and “salubrious climate.”

The hospital once housed 9,000 people, including patients and staff.

With funding in place, the construction of the Rockland State Hospital for the Insane moved forward at a staggering pace. Townspeople looked on as the monstrous institution swallowed up tract after tract of farms, houses, and undeveloped land. As patients flooded into the new buildings by the thousands, escapes became a regular occurrence. The “potential menace” of this “new and formidable population of undesirable outsiders” was a cause of great concern for locals. Infrequent but grisly murders in the vicinity of the hospital were attributed to “mentally disturbed” escapees. But the real horrors were occurring on the inside, as many of Orangeburg’s citizens could personally attest to–the institution was one of the largest job providers in the county.

Chipped plaster, masonry, paint, and wallpaper fill a water basin.

The real trouble started during World War II, when lucrative war industry jobs lured much of the staff away and a large number of Rockland’s male attendants left to join the armed forces. As the population soared to nearly 9,000, patient-to-staff ratios plummeted. “The work is hard, disagreeable and frequently dangerous, and the hospital has found it next to impossible to recruit employees.” New hires during this period were often untrained and unqualified. From a 1940s Times article: “An employment bureau in New York City sent a number of applicants here, but most of them were found to be suffering from arthritis, cardiac ailments or “unnatural” temperament and had to be sent home. ‘Some of them should be patients,’ Dr. Blaisdell said.”

A stash of nudie magazines hidden long ago in the basement of a kitchen area.

Like most all institutions operating during this period, the overcrowding and lack of effective treatment led to systemic abuse and negligence. Until the development of antipsychotic drugs in the 1960s, shock therapy and lobotomy were the only treatment methods available for severe cases of schizophrenia and other mental illnesses. As the century progressed and the new drugs became readily available, most patients were able to live independently outside of the asylum system. Since the 1970s, Rockland Psychiatric Center (as it is now known) has predominantly been used as an outpatient facility. By 1999 it housed less than 600 patients. Several new facilities were constructed in more recent years for outpatient care, but vast expanses of the 600 acre campus are entirely empty.

Mattresses piled up in a dayroom.

Today, a grid of overgrown streets divides a vast configuration of maze-like buildings known only by number. These were separate wards for men, women, children, and other subsets of the population like the infirm, the violent, and the criminally insane. Others were workshops, auditoriums, power plants, administration buildings, staff housing… the list goes on and on.

Exploring the buildings can be confusing and perilous. One ward’s heavy wooden doors had the nasty habit of slamming shut and refusing to open again, which can be a serious situation when there’s only one or two ways out. My solution was a series of improvised doorstops–beer cans, scraps of debris, whatever I could get my hands on–which doubled as a trail of breadcrumbs to give me a reasonable hope of finding my way out again.

One of Rockland’s most interesting features is the old four lane bowling alley. It’s a heavily trafficked area full of tempting props. Pins, balls, shoes, and trophies have been endlessly moved around, manipulated, and arranged into perfect triangles in the middle of the lanes. While I don’t blame fellow photographers for this sort of thing, it can be disappointing to walk into something that looks more like a stage set than a wild, unpredictable ruin. I’ll take that over the mindless graffiti–some if which I removed with a little Photoshop magic in the images below.

Despite all the modern mischief making, the bowling alley represents the best intentions of the institution to provide quality of life to patients who spent their lives at Rockland. These lanes must have been a welcome distraction from the monotony of asylum living.

Stay tuned for an upcoming post on the Rockland Children’s Hospital, which features an impressive collection of WPA murals.

A well-preserved bowling alley was located on the ground floor of a recreation building.

Blank score sheets could be found behind the ball return.

The AMF bowling equipment may date back to the 60s or 70s.

Bowling balls pile up at the end of the lanes from previous visitors.

Compared to the bowling balls, the pins were scarce. Many had been stolen over the years.

Wood shelving used for bowling shoes, once arranged by size.

Trophies for male and female bowlers.

Tomb Raiding in the Old Dutch Cemetery

Just a few paces into the woods behind the Old Dutch Church, the air grows thick with mosquitoes—that’s because the ground is full of damp, dark places where the bloodsuckers lurk and breed. To your left, bricks crumble from a row of gaping hillside mausoleums, and jagged headstones stretch as far as the eye can see through the thick overgrowth beyond. Though it stands just a few yards from the organization charged with its care, the Old Dutch Cemetery has been kept out of sight and completely abandoned for decades, which means this place doesn’t get many visitors, and these mosquitoes aim to eat you alive.

I don’t know all the particulars, but it’s difficult to understand how a church that has been in constant operation since the early 19th century could allow its historic graveyard to end up in such disrepair. In some cases, other parties have stepped in to take responsibility. Near the entrance to the church, an engraved monument lists the achievements of one of America’s founding fathers, whose remains were removed from the cemetery and relocated to his home city of Augusta, Georgia in 1973. Though the plaque makes no mention of it, the move probably had something to do with the poor condition of his family vault, which was built into the hillside directly behind the church along with several others.

All of the original residents of these burial chambers were reinterred elsewhere when the discovery of exposed human remains caused a public outcry many years ago. Today, the structures are empty, falling apart, and completely open to the elements and curious passersby. Though they appear to be very crudely built, they were more respectable in the first half of the 19th century, finished with slabs of engraved limestone that are currently piled up in pieces just outside the tombs. You can still make out a few fragments of the family names.

In the vaults, the number of mosquitoes reaches a level of absurdity you’d never thought possible. Inside the largest of them, a strange collection of trinkets comes into view as your eyes grow accustomed to the gloom—tiki men, Christmas stars, and Care Bears peer out from nooks and crannies in the walls and ceiling. Regarding their origin, my best guess is that the objects were left by visitors in atonement for disturbing the grave, or simply as a way of thanking the dead for playing host to an illicit night of partying. Sure enough, the ground is covered with malt liquor bottles; apparently there are more than a few residents of this sleepy town who consider getting drunk in an empty tomb a perfectly reasonable way to spend a Saturday night.

If you look carefully past all the modern refuse, a couple of eerie artifacts are scattered about, including a nearly intact 19th century casket handle and a segment of a second handle in a slightly different style. As tempted as I was to take these home, I figured that might be a good way to invite a ghostly possession into my life, not to mention a grave robbing charge, which could prove difficult to explain to future employers.

Past the hillside, a large number of monuments have fallen over or are dangerously close to doing so, several are broken or missing pieces, and all are steadily being consumed by the surrounding wilderness. Dating as far back as 1813 and as late as the early 20th century, the modest headstones represent a range of statuary typical for the period. For the most part there’s nothing distinctive about them, with one notable exception—an obelisk etched with the face of a sideburned young man, who seems to be the only one keeping watch over the Old Dutch Cemetery these days. By the looks of him, he strongly disapproves.

(Note: I’ve decided to thinly disguise the actual name and location of the church and cemetery, it has no relation to the Old Dutch Church in Sleepy Hollow, NY.)

A lounge chair and Christmas ornament (left) were left behind by previous visitors to the largest grave.

The Church itself, an elegant Victorian Gothic construction rebuilt in 1859, is in excellent condition.

The “Haunting” of Wyndclyffe Mansion

The Hudson River Valley is home to more than its share of formidable ruins, but few match the spooky appeal of Rhinebeck’s Wyndclyffe Mansion. Its beetle-browed exterior is blessed with that beguiling combination of gloom, ornamentation, and extreme old age that only the best haunted houses claim, and there’s no better time to witness them than late October, when autumn breezes send yellow leaves eddying through the hills and hollows of the old estate. It seems that the only thing this “haunted house” is missing is a good ghost story…

Much of what remains of the interior is far too unstable to access, this was taken from a window on the west side of the structure.

Murder, mayhem, and the supernatural don’t factor at all into the history of Wyndclyffe, but its past is compelling enough as it is. The manor was constructed in 1853 as the private country house of Elizabeth Schermerhorn Jones, who was a prominent member of an exceptionally wealthy New York family. Though palatial Hudson Valley estates were already in vogue among New York City’s ruling class, the magnificence of Wyndclyffe prompted neighboring aristocrats to throw even more money into their vacation homes so as not to be overshadowed by Elizabeth’s Rhinebeck abode. The house and the fury of construction it inspired is said to be the origin of the phrase, “keeping up with the Joneses.”

Elizabeth was the aunt of the great American author Edith Wharton, who is known for her keen, first-hand insight into the lives of America’s most privileged, which she brought to bear in classics like Ethan Frome, The House of Mirth, and The Age of Innocence, for which she won the Pulitzer Prize. (She’s also known for her ghost stories.) In her early youth, Edith would spend summers in the house, which was known by her as “Rhinecliff.” She portrayed it in less than laudatory terms in her late-career autobiography “A Backward Glance” (1934):

“The effect of terror produced by the house at Rhinecliff was no doubt due to what seemed to me its intolerable ugliness… I can still remember hating everything at Rhinecliff, which, as I saw, on rediscovering it some years later, was an expensive but dour specimen of Hudson River Gothic: and from the first I was obscurely conscious of a queer resemblance between the granitic exterior of Aunt Elizabeth and her grimly comfortable home, between her battlemented caps and the turrets of Rhinecliff.”

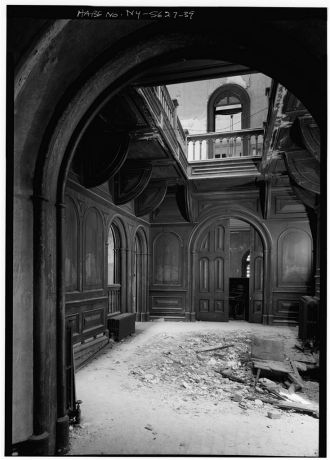

Many of the original architectural details are still visible in a collapsed section of the building, notice the wood detailing in the second floor parlor.

Her words bring to mind this passage from Shirley Jackson’s “The Haunting of Hill House” which describes the titular (fictional) structure:

“No human eye can isolate the unhappy coincidence of line and place which suggests evil in the face of a house, and yet somehow a maniac juxtaposition, a badly turned angle, some chance meeting of roof and sky, turned Hill House into a place of despair, more frightening because the face of Hill House seemed awake, with a watchfulness from the blank windows and a touch of glee in the eyebrow of a cornice. Almost any house…can catch up a beholder with a sense of fellowship; but a house arrogant and hating, never off guard, can only be evil.”

Here’s the same room pictured in the 1970s, with the floor already severely damaged by a leaky skylight.

The modern eye is likely to be much more merciful to the embattled Wyndclyffe, evil or no. Its beauty is readily apparent, and arguably enhanced, by the extent of decay it has suffered through 50 years of neglect. But how does a house as expensive, distinctive, and historically relevant as Wyndclyffe end up in such a state?

When Elizabeth passed away in 1876, Wyndclyffe was sold to a family who maintained the house into the 1920s, but the succession of owners that occupied the mansion through the Great Depression struggled to keep up with the costly repairs it required. In the 1970s, the house had already been abandoned for decades as the Hudson Valley’s status as a playground for the wealthy declined. At this point, the property was purchased and subdivided, which pared down the grounds of the estate from 80 acres to a paltry two and half. This action more than any other spelled doom for Wyndcliffe—notwithstanding the astronomical expense required to renovate a partially collapsed 160 year old mansion, the lack of land surrounding the structure has made it an extremely difficult sell to potential buyers. While many nearby estates have been renovated into thriving historic sites after a period of neglect, Wyndclyffe has struggled even to remain standing.

A glimmer of hope appeared in 2003 when a new owner cleared most of the trees and overgrowth from the grounds, erected a fence, and announced plans to save the mansion. But as is often the case, good intentions fade in the face of financial realities. Eleven years have come and gone and the meager improvements are difficult to discern—thick saplings, tangled thorns, and shrubbery completely envelop the structure once again, and the progress of decay marches on.

Numerous “No Trespassing” signs are posted around the property. State troopers are often summoned to the site when nearby homeowners alert them to suspicious activity.

Since Halloween is just around the corner, I’ll leave you with another eerie passage from Jackson’s “Haunting,” which is said by Stephen King (who should know) to be the best opening paragraph of any modern horror story. It deftly captures the uncanny appeal of empty buildings, and the persistent, however illogical, impression that a house continues to think, feel, and ruminate over its past long after it’s left behind by man.

“No live organism can continue for long to exist sanely under conditions of absolute reality; even larks and katydids are supposed, by some, to dream. Hill House, not sane, stood by itself against its hills, holding darkness within; it had stood so for eighty years and might stand for eighty more. Within, walls continued upright, bricks met neatly, floors were firm, and doors were sensibly shut: silence lay steadily against the wood and stone of Hill House, and whatever walked there, walked alone.”

Snooping in Storybook Castle

The entrance to Storybook Castle.

A deserted castle in the woods always has a few stories to tell. Maybe you’ve heard of the heart-shaped pools at Storybook that fill with blood on a full moon, or the Rapunzel-inspired succubus who hangs her hair to tempt gullible fishermen to their doom in the highest tower. Locals will tell you about the mad widow kept locked in a room with no doorknobs, who escaped on occasion to ride through town on horseback tossing gifts to children. (Supposedly, you can still find scratch marks where she clawed her way out.)

Most of these stories don’t hold water, of course, but the truth is nearly as strange. For starters, no one has ever lived in the castle.

The facts are few but generally accepted. Construction began in 1907 by a prominent New Yorker and heir to the builder of a famous canal. He transformed a nondescript wooden lodge that already stood on the property into a fanciful fairy tale castle modeled after a Scottish design, cutting corners with local river rocks on the facade but indulging in fine imported marble for the interior. Some say the castle was built out of love for his ailing wife, who suffered from mental illness. Unfortunately, the owner died in 1921 just before the structure was completed. Instead of moving into the romantic hideaway, his grieving widow was checked into a sanatorium shortly thereafter. The couple’s daughter and sole heir ran off to Europe with a new husband, leaving a caretaker to look after the unfinished castle.

The courtyard out back is periodically maintained, the lawn appeared to have been mowed recently.

In 1949, the property was purchased by the Prince Hall Grand Lodge of the Masonic Order, an African American group based in Manhattan. The original plan was to convert the castle to a masonic home for the elderly, but it was instead used for many years as a hunting and fishing resort. Later, the property became a summer camp for inner-city youth. As far as I can tell, the expansive grounds still serve this function today, though the castle itself has reportedly only been used to creep out campers over the years. There may be no more fertile ground for legends than a summer camp set in the vicinity of a derelict castle. Tales of glowing green eyes, apparitions in white, moving portraits, and self-slamming doors abound.

In 2005, the Prince Hall Masons and the Open Space Initiative announced an agreement to protect the castle and surrounding land, limiting future development and prohibiting residential subdivision. Unfortunately, nearly 10 years later, the castle is left completely vulnerable to vandals and exposed to the elements. Though the interior is remarkably well-preserved, several rooms are tagged up with uninspired graffiti. For this reason, I’ve chosen not to reveal the true name or location of the castle, be advised that the building is located on private property.

Click through the gallery to see the interior:

Kings Park Psychiatric Center’s Building 93

Kings Park Psychiatric Center’s Building 93

The ruins of Long Island’s Kings Park Psychiatric Center are often described as the perfect setting for a horror movie, and sure enough, several have been shot here. Poe and Lovecraft’s narrators may have been writing from asylum cells, but today’s horror heroes are venturing inside the abandoned ones. As shuttered institutions across the United States fall into decay, the insane asylum is showing up with increasing regularity in our scary movies, TV shows, books, and urban legends, quickly becoming synonymous with vengeful spirits, villainous doctors, and murderous mental patients. But while we may enjoy the “thrill of the shudder” while looking back at these places, we should be wary of reinforcing the stigma of mental illness and overlooking the nuanced history of American institutions.

A craft room on the ground floor still held looms and half finished rugs. (Prints Available)

Established in 1885 by the city of Brooklyn prior to the consolidation of the five boroughs, Kings County Asylum followed the farm colony model popular at the time, designed as a self-sufficient community where residents were put to work raising crops and livestock to support the sprawling campus. The labor was thought to be therapeutic, occupying the time and attention of residents and keeping costs down. Early in its history, Kings Park was composed of a group of cottages meant to avoid the high rise asylum model which was already viewed as inhumane. But demand soared as the population skyrocketed in New York City into the 1930s, and in 1939 the institution resorted to constructing Building 93, a 13-story structure whose design was strikingly similar to what it had sought to avoid. At its peak in the 1950s, Kings Park reached a population of over 9,000 residents, who were divided by gender, age, temperament, and physical limitations through a complex of over 100 buildings, which included power plants, fire stations, staff housing, hospitals, recreational facilities, piggeries, and cow barns.

Beds may have been moved down in 1996 when Kings Park’s last residents were relocated to nearby Pilgrim State.

Furniture and equipment left behind on the ground floor.

Throughout its history, Kings Park was notable for staying on the cutting edge of psychological science, cementing its place in history as an early adopter and proponent of a succession of new procedures and medications that eventually led to the institution’s decline. In the first half of the 20th century, the psychological community was in a state of desperation, charged with the task of caring for a growing number of mentally ill patients with few treatment options available aside from psychotherapy and the rampant use of restraints and confinement. The 1940s saw the rise of two groundbreaking, albeit crude, procedures that gave doctors effective tools to manage extremely disturbed patients for the first time.

Shock therapy was conceived when doctors observed that the mood of epileptic patients suffering from depression improved after a seizure. The procedure aimed to replicate these benefits by inducing a seizure through electricity or insulin injection. Electroconvulsive therapy, as it’s known today, is still considered an effective treatment, even having a resurgence in recent years. But today’s advanced anesthesia and precise control of the duration and physical effects of seizures is a far cry from what patients went through in the 1940s. Strapped fully conscious to a hospital bed, patients could convulse for up to fifteen minutes at a time, often with enough force to fracture and break bones. Once a patient was admitted to an asylum, they had no right to give or deny consent for these procedures, and in many cases, shock therapy was used as a punitive measure to keep unruly residents in line.

Early diagram of a transorbital lobotomy.

The lobotomy is remembered as one of the most grotesque treatment methods of the era. It was a simple procedure, in which a metal tool was inserted through the eye socket into the skull cavity, and wrenched around to sever the connections of the pre-frontal cortex from the rest of the brain. It was an imprecise and brutal operation, which left lobotomized individuals with no trace of their former selves. Though proponents of the procedure called these results a “second childhood,” lobotomized patients might have been more accurately described as zombies—extremely violent and disturbed residents would be rendered permanently docile, passive, and easy to control. Though it was controversial even in its time, its first proponents were awarded a Nobel Peace Prize in 1949 for their discovery.

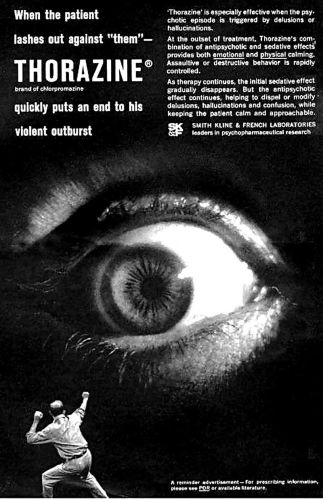

A 1960s advertisement for antipsychotic medication.

The development of effective antipsychotic medication in the mid-1950s signaled the decline of these extreme measures and the institution system as a whole. For the first time, residents once considered hopeless were able to manage their mental illness and live independently. This led to a dramatic shift in institutions across the country from severe overcrowding to near-abandonment as a trend of deinstitutionalization swept through America into the 80s and 90s. But as anxious as the powers that be were to put this dark period of history behind them (and cut funding out of state budgets,) they may have done too much too soon. While medication has made it possible for most people living with severe mental disorders to function on their own, there is still a sizable percentage for whom the available medications are ineffective. Reputable group homes for the mentally ill are few and far between, and out of reach for individuals without a solid support system in place. Many suffering from severe mental illness today are living on the streets, and a growing number end up incarcerated, without proper access to quality psychiatric care. Today, Kings Park stands as a testament to a bygone era, but the problem it sought to address remains unsolved.

Layers of colored paint peel from a hallway of isolation rooms. (Prints Available)

Lower floors housed able-bodied residents with large day rooms, while the infirm were confined to the upper levels.

Each floor was nearly identical, with subtle variations in color and layout.

A central hallway connected day rooms, dormitories, dining halls, and isolation chambers. (Prints Available)

Patient rooms leading to the cafeteria.

Vines overtaking the exterior of Building 93.

Check out Part 1 of “A History Abandoned” from Vocativ.com, which follows me on an exploration through three NYC institutions. First up, Kings Park:

Talking Trash in Dubos Point Wildlife Sanctuary

Take the A train past JFK. You’ll be one of a handful of travelers left on a car that seemed well over capacity a moment ago; the babble of the crowd fades to the soft hum of an unimpeded machine. Nobody asks you for money, or directions. If you’ve made it this far, you know where you’re going.

Suddenly, the ground drops out and you’re gliding over the silver Jamaica Bay. The train runs just above sea level, skimming over a surface that teems visibly with diving cormorants. Clustered with skeletal boat frames, aged marinas jut from a neglected shoreline across the water, to the west, a row of painted houses stand on stilts. There’s no place like the Rockaways to experience New York as a city by the sea.

Head east at Hammels Wye, and a brief walk through the quiet neighborhood of Averne will lead you to a little known peninsula called Dubos Point, one of the last fragments of salt marsh left in a city that was once ringed with tidal wetlands. The marsh was filled with dredged materials in 1912 in preparation for an ill-fated real estate development, but over the last century, the area has reverted to its natural state. In 1988, the land was acquired by the Parks Department, deemed a wildlife sanctuary, and given an official name for the first time (Rene Dubos was a microbiologist and environmental activist who coined the phrase “Think Globally, Act Locally”).

Parks officials envisioned marked nature trails and boardwalks for community use, and planned to build nesting structures and employ part-time patrol staff to encourage wildlife and keep the place clean, but none of this came to be. The Audubon Society of New York maintained the grounds sporadically until 1999, but abandoned its post citing a lack of resources. Since then, the area has been largely neglected, leaving its care up to volunteers. Green Apple Corps and the Rockaway Waterfront Alliance have orchestrated several clean-up events over the years, but they’re facing an uphill battle.

Every day, the shores of Dubos Point are bombarded with an onslaught of garbage, and it’s not coming from park visitors (the preserve is technically not open to the public). Most of the refuse is washed up from the bay, after a long journey through storm drains that began in the littered streets of New York City. Familiar objects are made strange, touched by a long encounter with an invisible world, caked with green algae, eroded with salt, barnacle-burdened and bleached by the sun. The entire peninsula resounds with the constant susurration of wind through grass. For all these reeds are hiding, perhaps they whisper secrets; mud-moored vessels, decaying toys, and saltbored furniture lay half-concealed in the tidal growth.

Standing water in old tires and plastic debris makes for a perfect breeding ground for the area’s most populous species. My first steps onto the grounds of Dubos Point seemed to disturb some ancient curse, as great swarms of mosquitoes rose from their stagnant hollows to draw my blood sacrifice. The Parks department has been criticized in the past for neglecting its duties at Dubos Point while mosquito infestation reached “plague proportions” in the late 90s, rendering backyards unusable from April to October. After years of complaints and little improvement, some residents resorted to building outdoor shelters for brown bats, a natural insect predator. Today, the only visible improvement made on the grounds of Dubos Point is a line of Mosquito Magnet kiosks, placed every 100 feet along the boundary of the preserve.

Despite decades of pollution, the Jamaica Bay harbors hundreds of species of wildlife, and the water is cleaner today than it was 100 years ago. As one of the last remaining pockets of undeveloped land in New York, the estuary supplies an essential resting place for migratory birds along the Atlantic Flyway; egrets, herons, and peregrine falcons are spotted here. Looking past the garbage, you can still make out the natural beauty of Dubos Point, and imagine what this whole region was like 400 years ago. Neck-high cordgrass is abundant, trapping bits of decayed organisms to fuel a thriving, though limited, ecosystem. Throngs of fiddler crabs crowd the soggy ground, scuttling sideways with one collective mind, crunching underfoot like eggshells. The breezy silence is only interrupted by an occasional splash from a jumping fish, or the roar of a plane, taking off from the crowded runways of JFK just across the water. Off the curling tip of Dubos Point, fishermen still cast their lines in the Sommerville Basin, affirming a bond we’ve all but lost.

12,000 of the original 16,000 acres of wetlands around the Jamaica Bay have already been filled in for development, and sources predict that the last of the saltwater marshes could disappear in the next 20 years. It’s a shame to see one of the few protected areas in this condition, when its potential for education and recreation is so apparent. New York needs to protect its wild spaces, and sometimes that means getting our hands dirty. To learn about volunteer opportunities with the Parks Department, visit their website. And check back for information on the next Dubos Point clean-up.

Checking in to Grossinger’s Resort

The ransacked Paul G. hotel, showing the hallmarks of a recent paintball game.

Past a deserted security desk, waist-high grasses choke back the yawning entrance to the Jennie G. Hotel, whose toppled fence serves more as an invitation than a barrier. Here in the sleepy town of Liberty, NY, this derelict hilltop lodge is not only a destination for the curious, it’s a daily reminder of the town’s old eminence, an emblem of a dead industry, visible from miles around.

In its time, Grossinger’s Catskills Resort was a fantasy realized, where wealthy businessmen, celebrity entertainers, and star athletes gathered to mingle with those that they liked and were like, to see and be seen, and to enjoy, rightly so, the things they enjoyed. As the slogan goes—Grossinger’s has Everything for the Kind of Person who Likes to Come to Grossinger’s.

Flowers left by a former guest, or a prop from an old photo shoot.

If you’re the kind of person that’s inclined to spend their vacation somewhere dark, dusty, and dangerous, the motto still rings true today, and you’re not coming for the five-star kosher kitchen. For just as quickly as the resort prospered into a world-class institution, it’s descended into a swift decay. Explorers frequent the grounds, armed with cameras in an attempt to capture the beauty in its devastation, sifting through the artifacts—a broken lounge chair, old reservation records—piecing together a lost age of tourism.

A generation ago, this region of the Catskills was known as the Borscht Belt, a tongue-in-cheek designation for a string of hotels and resorts that catered to a predominantly Jewish customer base in a time when discrimination against Jews at mainstream resorts was widespread. In popular culture, the most notable representation of this time and place is Dirty Dancing, which was supposedly inspired by a summer at Grossinger’s. The unexpected success of its film adaptation had little effect on the long-struggling resort—in 1986, a year before the film was released, Grossinger’s ended its 70 year legacy.

The story of Grossinger’s is, at its root, an American story. The Grossingers were Austrian immigrants, who after some early years of struggle in New York City, and a failed farming venture, opened a small farmhouse to boarders in 1914, without plumbing or electricity. They quickly gained a reputation for their exceptional hospitality and incredible kosher cooking and outgrew the ramshackle farmhouse, purchasing the property that the resort still occupies today.

Grossinger’s rise to prominence is largely attributed to the couple’s daughter Jennie, who worked there as a hostess in its early years. Later, Jennie’s legendary leadership would transform the resort from its humble beginnings to a massive 35-building complex (with its own zip code and airstrip), attracting over 150,000 guests a year, and establishing a new type of travel destination that renounced the quiet charms of country living for a fast-paced, action-packed social experience that met the expectations of its sophisticated New York clientele.

Remnants of an attempt to burn down the Jennie G.

Every sport of leisure had its own arena, with state of the art facilities for handball, tennis, skiing, ice skating, barrel jumping, and tobogganing, along with a championship golf course. In 1952, the resort earned a place in history by being the first to use artificial snow. Its famous training establishment for boxers hosted seven world champions. Its stages launched the careers of countless well-known singers and comedians. In its day spas and beauty salons, ballrooms and auditoriums, guests were offered a level of luxury that even the wealthiest individuals couldn’t enjoy at home, earning Grossinger’s the nickname, “Waldorf in the Catskills.”

A daily missive called The Tattler identified notable guests and the business that made their respective fortunes. Weekly tabloids published on the grounds boasted the presence of celebrity athletes and entertainers. But for all the emphasis on earthly pleasures and material wealth, Jennie G. ensured that the Grossinger’s experience was warm and personal, always treating guests like one of the family, even when visitors reached well over 1,000 per week.

By the late sixties, the Grossinger’s model had started to fall out of favor as cheap air travel to tourist destinations around the world became readily available to a new generation. After the property was abandoned, several renovation attempts were aborted by a string of investors. Widespread demolition has greatly diminished the sprawl of the original resort, but several of the largest buildings remain. Most have been stripped of any vestige of opulence, and some structures are barely standing; no more so than the former Joy Cottage, whose floors might not withstand the footfalls of a field mouse.

Artifacts from the hotel’s glory days are few and far between, but Grossinger’s most recent batch of visitors has been quick to leave its mark. In a haunting hotel filled with empty rooms, some scenes are startlingly arranged, with collected mementos photogenically poised in the pursuit of a compelling shot. Despite these attempts to prettify Grossinger’s decline, the grounds retain an air of savage dilapidation, and an utter submission to nature.

An indoor swimming pool is Grossinger’s most enduring spectacle, and has become a favorite location of urban explorers near and far. Radiance remains in its terra-cotta tiles and its well-preserved space age light fixtures. Its dimensions continue to impress, as do the postcard views through its towering glass walls, all miraculously intact. It’s growth, not decay, that makes this pool so picturesque—the years have transformed this neglected natatorium into a flourishing greenhouse. Ferns prosper from a moss-caked poolside, unhindered by the tread of carefree vacationers, urged by a ceiling that constantly drips. Year-round scents of summer have bowed to a kind of perpetual spring, with the reek of chlorine and suntan lotion replaced by the heady odor of moss and mildew—it’s dank, green, and vibrantly alive.

Meanwhile, areas across the region that once relied on a thriving tourism industry have fallen into depression or emptied out. The Catskills is attempting to rebrand, updating its image and holding online contests to determine a new slogan. The winner? The Catskills, Always in Season.

Though it remains to be seen whether the coming seasons will bring new visitors, there’s no doubt they’re serving to erase the region’s outmoded reputation. With each passing year, in ruined hotels across the Catskills, the physical remnants of lost vacations dwindle. Indoors, snowdrifts weigh on aching floors; leaf litter collects to harbor the damp or fuel the fire. Vines claim what the rain leaves behind, compelling the constant progress of decay. Scattered in photo albums, hidden in bottom drawers, excerpted from yellowing newsprint, the memories will follow, clearing the way for new journeys. Before it’s forgotten, here’s one more look inside the celebrated resort.

This catwalk ensured a comfortable commute from your suite at the Paul G. to the indoor pool year-round.

A pitch-black beauty salon lit with the aid of a flashlight.

The ruined entrance to the hotel spa.

Office on the bottom floor of the Jennie G. Hotel.

The best preserved room, with two murphy beds, and a carpet of moss.

In most rooms, peeling wallpaper was all that remained.

The ground floor of the management office, now on the verge of collapse.

Hotel records neatly arranged on a mattress, by a photographer, no doubt.

Legend Tripping in Letchworth Village

Letchworth Village rests on a placid corner of rural Thiells, a hamlet west of Haverstraw set amid the gentle hills and vales of the surrounding Ramapos. A short stretch of modest farmhouses separates this former home for the mentally disabled from the serene Harriman State Park, New York’s second largest. Nature has been quick to reclaim its dominion over these unhallowed grounds, shrouding an unpleasant memory in a thick green veil. Abandonment becomes this “village of secrets,” intended from its inception to be unseen, forgotten, and silent as the tomb.

Owing to its reputed paranormal eccentricities, Letchworth Village has become a well-known subject of local legend. These strange tales had me spooked as I turned the corner onto Letchworth Village Road after a suspenseful two-hour drive from Brooklyn. Rounding a declining bend, I caught my first glimpse of Letchworth’s sprawling decay—some vine-encumbered ruin made momentarily visible through a stand of oak. Down the hazy horseshoe lanes of the boy’s ward, one by one, the ghosts came out.

By the end of 1911, the first phase of construction had completed on this 2,362 acre “state institution for the segregation of the epileptic and feeble-minded.” With architecture modeled after Monticello, the picturesque community was lauded as a model institution for the treatment of the developmentally disabled, a humane alternative to high-rise asylums, having been founded on several guiding principles that were revolutionary at the time.

The Minnisceongo Creek cuts the grounds in two, delineating areas for the two sexes which were meant never to mingle. Separate living and training facilities for children, able-bodied adults, and the infirm were not to exceed two stories or house over 70 inmates. Until the 1960s, the able-bodied labored on communal farms, raising enough food and livestock to feed the entire population.

Sinister by today’s standards, the “laboratory purpose” was another essential tenet of the Letchworth plan. Unable to give or deny consent, many children became unwitting test subjects—in 1950, the institution gained notoriety as the site of one of the first human trials of a still-experimental polio vaccine. Brain specimens were harvested from deceased residents and stored in jars of formaldehyde, put on display in the hospital lab. This horrific practice has become a favorite anecdote of ghost-hunters and adolescent explorers.

The well-intentioned plans for Letchworth Village didn’t hold up in practice, and by 1942, the population had swelled to twice its intended occupancy. From here, the severely underfunded facility fell into a lengthy decline. Many of the residents, whose condition necessitated ample time and attention for feeding, became seriously ill or malnourished as a result of overcrowding. At one point, over 500 patients slept on mattresses in hallways and dayrooms of the facility, meagerly attended by a completely overwhelmed staff tasked with the impossible.

Having discontinued the use of the majority of its structures, and relocated most of its charges into group homes, the institution closed down in 1996 as old methods of segregating the developmentally disabled were replaced with a trend toward normalization and inclusion into society. The state has made efforts to sell the property, with mixed results. Most of the dilapidated structures were slated for demolition in 2004 to make way for a 450-unit condo development, but the plan has evidently been put on hold. Ringed with ballfields and parking lots, shiny Fieldstone Middle School makes use of nine buildings of the former girl’s group, an island of promise in a landscape of failure.

Off Call Hollow Road, a new sign has been erected pointing out the “Old Letchworth Village Cemetery.” Down a seldom-traveled path, an unusual crop of T-shaped markers congregate on a dappled clearing. They’re graves, but they bear no names.

Few wished to remember their “defective” relatives, or have their family names inscribed in such a dishonorable cemetery—many family secrets are buried among these 900 deceased. Here, in the presence of so many human lives devalued, displaced, and forgotten, the sorrow of Letchworth Village is keenly felt.

As part of a movement taking place across the country, state agencies and advocates funded the installation of a permanent plaque inscribed with the names of these silent dead, and a fitting epitaph: “To Those Who Shall Not Be Forgotten.”

Moments after taking this photo, a group of young explorers entered through a side door. I gave them quite a scare.

A strange camera malfunction lasted the entire time I was in this building and stopped the moment I stepped out. It’s the closest I came to a paranormal experience.

Houdini’s Grave, in NYC’s Spookiest Cemetery

Are we in Queens or Salem’s Lot?

If you pass by a graveyard on the Jackie Robinson Parkway, don’t hold your breath. You’ve got two and half miles of Queens’ Cemetery Belt ahead of you, a burial ground so vast it’s supposedly visible from space. Surrounded on all sides by an ocean of headstones, the modest Machpelah Cemetery makes up only a small fraction of the sprawling necropolis, but its arguably the creepiest graveyard in the city…

Cramped centenarian tombstones muster in rows on the hilly plot—the place is rundown and deserted, but one grave is consistently well-maintained. It’s the monument of Machpelah’s most famous resident, master escape artist Harry Houdini. Only steps from the headstone lurks an eerie cemetery office, abandoned since the late 80s. The cemetery is a dream destination for graveyard ghouls on a chilly October night, especially since Halloween marks the anniversary of Houdini’s untimely death.

The history of the Cemetery Belt can be traced back to the Rural Cemeteries Act of 1847, under which cemeteries became a legitimate commercial enterprise for the first time in New York. Non-profit organizations were authorized to buy up land and sell plots to individuals, replacing the traditional practice of burying the deceased in churchyards and private property.

Areas of then-rural Queens quickly became concentrated with new cemetery holdings. A stipulation of the act limited the acreage of land an organization could purchase in a given county, but church groups and land speculators got around this by buying up neighboring plots on the Brooklyn-Queens border, forming the region now known as the Cemetery Belt.

Between 1832 and 1849, a series of cholera outbreaks thoroughly exhausted Manhattan’s remaining burial sites. The common belief at the time was that ground water could become contaminated with the disease when infected corpses were exposed to the soil. As a result, all burials were prohibited on the island of Manhattan in 1852.

As the population swelled, new developments, including the Brooklyn Bridge, often required the displacement of grave sites. Manhattan started evicting its dead people, and sending them to western Queens—tens of thousands of deceased were disinterred and transported to mass graves in the Cemetery Belt. These ghoulish dealings were kept away from the public eye, often carried out in the dead of night.

Today, Queens’ five million “permanent residents” almost triple its living population, but their numbers are at a standstill. Most of these cemeteries reached capacity long ago, leaving many without a source of income. As a result, some have fallen into disrepair, with officials failing to provide the “perpetual care” their patrons are rightfully owed.

At the nearby Bayside Cemetery, conditions were downright shameful, and hair-raising—exposed human remains were identified at several of the overgrown grave sites. Community pressure, litigation, and the effort of volunteers have gotten the place cleaned up, albeit in a cursory fashion. Gaping mausoleums have been closed off with cinderblocks and boards.

At Machpelah, the plots are untidy, but not nearly as egregious as the Bayside grounds. The cemetery’s decline is most apparent in its ramshackle office building. The boarded-up structure is dilapidated now, but its architecture, dating to 1928, continues to impress on the surface.

Burial records litter the floor of the Machpelah Cemetery office.

Any semblance of grandeur breaks down on the inside. The striking arched windows visible in the facade are installed in rectangular frames, and their diamond panes are all artifice. The skeleton of a drop ceiling hangs askew, with most panels collapsed and reduced to a yellow paste that covers the ground. The office has apparently fallen victim to vandals over the years, furniture and safe deposit boxes have been ransacked, old burial records lie scattered in the grime. Anything of value has been removed, but a coin bank souvenir from the 1939 New York World’s Fair remains, its most recent deposits dating back to 1988.

“Stuffy” doesn’t begin to describe its suffocating ether. Reception rooms are boxed in with cheap wood paneling, which combines with the dizzying funk of mildew to evoke the interior of a coffin. Secluded in a cockeyed armoire, Nosferatu could feel right at home here.

Red roses wilt on Houdini’s grave.

Every Halloween, hundreds of devotees make the yearly pilgrimage to Houdini’s final resting place to pay their respects, party, and make an offering—around the anniversary of his death, pumpkins, broomsticks, and playing cards mount like a cairn on his headstone.

The Society of American Magicians, for which Houdini served as president until his death, was the official caretaker of the site until recently. Between 1975 and 1993, the bust that adorns the Houdini monument was stolen or destroyed four times—it’s thought to be the only graven image in any Jewish Cemetery.

For many years, the likeness was only brought out for yearly ceremonies, but in 2011, a group of magicians from the Scranton Houdini Museum engaged in some guerrilla restoration, installing a new bust with the blessing of Houdini’s family. The group has since taken over responsibilities for the site’s care, and so far the monument remains unscathed.

With no funds to reoccupy, renovate, or demolish the old office building, its likely to stand until it falls down on its own; the same can’t be said of Houdini’s shiny new effigy. Odds are he’ll lose his head again—even though it’s screwed on. So next time you’re traveling down that graveyard highway, be sure to stop by for a look while you can. There’s no need to wait for the witching hour. At Machpelah Cemetery, the gate is always open, and every day is Halloween.

UPDATE: The office was demolished on August 21st, 2013.

-Will Ellis

The lobby, with a distinctive arched doorway, bathed in golden morning light.

The second floor.

Valuable copper pipes were removed from the upstairs.

Several rooms feature vintage wallpaper, but wood paneling had been removed.

Sunlight illuminates a stairwell.

A forbidding basement. The structure could only be accessed through a narrow opening that led to this room.

No vacancy.

Dawn breaks on Houdini’s grave.