AbandonedNYC

Hudson Valley

Tomb Raiding in the Old Dutch Cemetery

Just a few paces into the woods behind the Old Dutch Church, the air grows thick with mosquitoes—that’s because the ground is full of damp, dark places where the bloodsuckers lurk and breed. To your left, bricks crumble from a row of gaping hillside mausoleums, and jagged headstones stretch as far as the eye can see through the thick overgrowth beyond. Though it stands just a few yards from the organization charged with its care, the Old Dutch Cemetery has been kept out of sight and completely abandoned for decades, which means this place doesn’t get many visitors, and these mosquitoes aim to eat you alive.

I don’t know all the particulars, but it’s difficult to understand how a church that has been in constant operation since the early 19th century could allow its historic graveyard to end up in such disrepair. In some cases, other parties have stepped in to take responsibility. Near the entrance to the church, an engraved monument lists the achievements of one of America’s founding fathers, whose remains were removed from the cemetery and relocated to his home city of Augusta, Georgia in 1973. Though the plaque makes no mention of it, the move probably had something to do with the poor condition of his family vault, which was built into the hillside directly behind the church along with several others.

All of the original residents of these burial chambers were reinterred elsewhere when the discovery of exposed human remains caused a public outcry many years ago. Today, the structures are empty, falling apart, and completely open to the elements and curious passersby. Though they appear to be very crudely built, they were more respectable in the first half of the 19th century, finished with slabs of engraved limestone that are currently piled up in pieces just outside the tombs. You can still make out a few fragments of the family names.

In the vaults, the number of mosquitoes reaches a level of absurdity you’d never thought possible. Inside the largest of them, a strange collection of trinkets comes into view as your eyes grow accustomed to the gloom—tiki men, Christmas stars, and Care Bears peer out from nooks and crannies in the walls and ceiling. Regarding their origin, my best guess is that the objects were left by visitors in atonement for disturbing the grave, or simply as a way of thanking the dead for playing host to an illicit night of partying. Sure enough, the ground is covered with malt liquor bottles; apparently there are more than a few residents of this sleepy town who consider getting drunk in an empty tomb a perfectly reasonable way to spend a Saturday night.

If you look carefully past all the modern refuse, a couple of eerie artifacts are scattered about, including a nearly intact 19th century casket handle and a segment of a second handle in a slightly different style. As tempted as I was to take these home, I figured that might be a good way to invite a ghostly possession into my life, not to mention a grave robbing charge, which could prove difficult to explain to future employers.

Past the hillside, a large number of monuments have fallen over or are dangerously close to doing so, several are broken or missing pieces, and all are steadily being consumed by the surrounding wilderness. Dating as far back as 1813 and as late as the early 20th century, the modest headstones represent a range of statuary typical for the period. For the most part there’s nothing distinctive about them, with one notable exception—an obelisk etched with the face of a sideburned young man, who seems to be the only one keeping watch over the Old Dutch Cemetery these days. By the looks of him, he strongly disapproves.

(Note: I’ve decided to thinly disguise the actual name and location of the church and cemetery, it has no relation to the Old Dutch Church in Sleepy Hollow, NY.)

A lounge chair and Christmas ornament (left) were left behind by previous visitors to the largest grave.

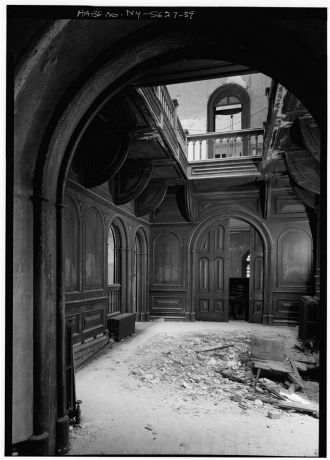

The Church itself, an elegant Victorian Gothic construction rebuilt in 1859, is in excellent condition.

The “Haunting” of Wyndclyffe Mansion

The Hudson River Valley is home to more than its share of formidable ruins, but few match the spooky appeal of Rhinebeck’s Wyndclyffe Mansion. Its beetle-browed exterior is blessed with that beguiling combination of gloom, ornamentation, and extreme old age that only the best haunted houses claim, and there’s no better time to witness them than late October, when autumn breezes send yellow leaves eddying through the hills and hollows of the old estate. It seems that the only thing this “haunted house” is missing is a good ghost story…

Much of what remains of the interior is far too unstable to access, this was taken from a window on the west side of the structure.

Murder, mayhem, and the supernatural don’t factor at all into the history of Wyndclyffe, but its past is compelling enough as it is. The manor was constructed in 1853 as the private country house of Elizabeth Schermerhorn Jones, who was a prominent member of an exceptionally wealthy New York family. Though palatial Hudson Valley estates were already in vogue among New York City’s ruling class, the magnificence of Wyndclyffe prompted neighboring aristocrats to throw even more money into their vacation homes so as not to be overshadowed by Elizabeth’s Rhinebeck abode. The house and the fury of construction it inspired is said to be the origin of the phrase, “keeping up with the Joneses.”

Elizabeth was the aunt of the great American author Edith Wharton, who is known for her keen, first-hand insight into the lives of America’s most privileged, which she brought to bear in classics like Ethan Frome, The House of Mirth, and The Age of Innocence, for which she won the Pulitzer Prize. (She’s also known for her ghost stories.) In her early youth, Edith would spend summers in the house, which was known by her as “Rhinecliff.” She portrayed it in less than laudatory terms in her late-career autobiography “A Backward Glance” (1934):

“The effect of terror produced by the house at Rhinecliff was no doubt due to what seemed to me its intolerable ugliness… I can still remember hating everything at Rhinecliff, which, as I saw, on rediscovering it some years later, was an expensive but dour specimen of Hudson River Gothic: and from the first I was obscurely conscious of a queer resemblance between the granitic exterior of Aunt Elizabeth and her grimly comfortable home, between her battlemented caps and the turrets of Rhinecliff.”

Many of the original architectural details are still visible in a collapsed section of the building, notice the wood detailing in the second floor parlor.

Her words bring to mind this passage from Shirley Jackson’s “The Haunting of Hill House” which describes the titular (fictional) structure:

“No human eye can isolate the unhappy coincidence of line and place which suggests evil in the face of a house, and yet somehow a maniac juxtaposition, a badly turned angle, some chance meeting of roof and sky, turned Hill House into a place of despair, more frightening because the face of Hill House seemed awake, with a watchfulness from the blank windows and a touch of glee in the eyebrow of a cornice. Almost any house…can catch up a beholder with a sense of fellowship; but a house arrogant and hating, never off guard, can only be evil.”

Here’s the same room pictured in the 1970s, with the floor already severely damaged by a leaky skylight.

The modern eye is likely to be much more merciful to the embattled Wyndclyffe, evil or no. Its beauty is readily apparent, and arguably enhanced, by the extent of decay it has suffered through 50 years of neglect. But how does a house as expensive, distinctive, and historically relevant as Wyndclyffe end up in such a state?

When Elizabeth passed away in 1876, Wyndclyffe was sold to a family who maintained the house into the 1920s, but the succession of owners that occupied the mansion through the Great Depression struggled to keep up with the costly repairs it required. In the 1970s, the house had already been abandoned for decades as the Hudson Valley’s status as a playground for the wealthy declined. At this point, the property was purchased and subdivided, which pared down the grounds of the estate from 80 acres to a paltry two and half. This action more than any other spelled doom for Wyndcliffe—notwithstanding the astronomical expense required to renovate a partially collapsed 160 year old mansion, the lack of land surrounding the structure has made it an extremely difficult sell to potential buyers. While many nearby estates have been renovated into thriving historic sites after a period of neglect, Wyndclyffe has struggled even to remain standing.

A glimmer of hope appeared in 2003 when a new owner cleared most of the trees and overgrowth from the grounds, erected a fence, and announced plans to save the mansion. But as is often the case, good intentions fade in the face of financial realities. Eleven years have come and gone and the meager improvements are difficult to discern—thick saplings, tangled thorns, and shrubbery completely envelop the structure once again, and the progress of decay marches on.

Numerous “No Trespassing” signs are posted around the property. State troopers are often summoned to the site when nearby homeowners alert them to suspicious activity.

Since Halloween is just around the corner, I’ll leave you with another eerie passage from Jackson’s “Haunting,” which is said by Stephen King (who should know) to be the best opening paragraph of any modern horror story. It deftly captures the uncanny appeal of empty buildings, and the persistent, however illogical, impression that a house continues to think, feel, and ruminate over its past long after it’s left behind by man.

“No live organism can continue for long to exist sanely under conditions of absolute reality; even larks and katydids are supposed, by some, to dream. Hill House, not sane, stood by itself against its hills, holding darkness within; it had stood so for eighty years and might stand for eighty more. Within, walls continued upright, bricks met neatly, floors were firm, and doors were sensibly shut: silence lay steadily against the wood and stone of Hill House, and whatever walked there, walked alone.”

The Trapps Mountain Hamlet, Backwoods Ghost Town

If you’re like me, city living can wear you down—sooner or later, you’re itching for the woods again. The sleepy college town of New Paltz offers a cheap motel and a short proximity to Mohonk Preserve, 5,000 acres of hiking trails, swimming holes, and rock scrambles nestled deep in the ancient Palisades. The world-worn hills of the Shawangunk Ridge evoke a pleasing sense of permanence to the weary New Yorker, it’s a lifetime away from the teeming avenues of Manhattan. Time seems to stand still around here, but out in these tall timbers, the ruins of a 19th century ghost town hint at a lost way of life.

The area is known for its landmark luxury resort, the Mohonk Mountain House, which has been run by the same family since it opened in 1869. True to its Quaker roots, the hotel originally banned liquor, dancing, and card playing; until 2006, it couldn’t claim a bar, and you still won’t find a TV or radio in any of the $700 a night lodgings. It may sound old-fashioned, but it’s part of a tradition in these parts—since they were first settled in the late 1700s, things have always been behind the times.

Before the age of mountain tourism, a small subsistence community lived off this land, growing what little food the thin, rocky soil could support, raising a handful of livestock, drinking from the Coxing and Peter’s Kills. They scraped a living carving millstone out of native rock, shaving barrel hoops, and harvesting tree bark for leather tanning. In the summer, women and children joined in harvesting huckleberries, a seasonal cash crop in wild abundance at the time.

With a peak population of forty or fifty families, the settlement included a hotel, a store, a chapel, and a one room schoolhouse. Despite this progress, the population held to its old ways. So hopelessly and wonderfully at odds with the changing values of the outside world, this oldfangled hamlet didn’t stand a chance.

Starting in the late 1800s, advances in technology gradually replaced the small trades of the Trapps. Unable to sell their traditional wares, settlers found work in neighboring resorts, including the Mohonk Mountain House, building hotels and maintaining trails and carriage roads. In the late 20s, the construction of Route 44 created a short term boom in the town’s employment, but eventually led to its decline.

Many sold their property to resort owners and headed to nearby villages to find a better way of life, but one man called Eli Van Leuven stayed behind, living in a tiny plank house without running water or electricity until his death in 1956.

The Van Leuven Cabin has been lovingly restored, an unassuming monument to a largely forgotten community. Aside from this, the humble industries of the two score families that resided here have left little to mark them but shallow depressions in the ground, rubble stacked in odd arrangements, and leaf-littered tombstones. Only a settlement so bound to the earth could disappear so completely.

On the drive home, the first sighting of the Manhattan skyline elicits a kind of dull horror, signaling the inevitable return to a concrete-bound existence. As I’m plunged back into the 21st century, the scene is at once overstimulating and shockingly mundane. In that moment, I’d take an axe and a cool morning in a mountain hamlet over any day in the ad-plastered streets of midtown, but the daydreams invariably dissolve. Out of habit, obligation, or common sense, I’ll forget the plank house for the brownstone, the Coxing Kill for the coffee shop, as the stony ruins of a mountain town blanket themselves in moss.

-Will Ellis

Former site of the Enderly House, most structures incorporated Native American techniques into their construction.

This road was built in large part by Trapps Hamlet residents. Today, it glides through the heart of the ghost town.

This boundary wall was used to delineate the property of Benjamin Fowler, who owned 150 acres for farming, livestock, and family use.

Many of Benjamin’s young children are buried in this forest plot. This grave for his son William is the earliest, dating to 1866.