AbandonedNYC

Industrial

Port Reading’s McMyler Coal Dumper

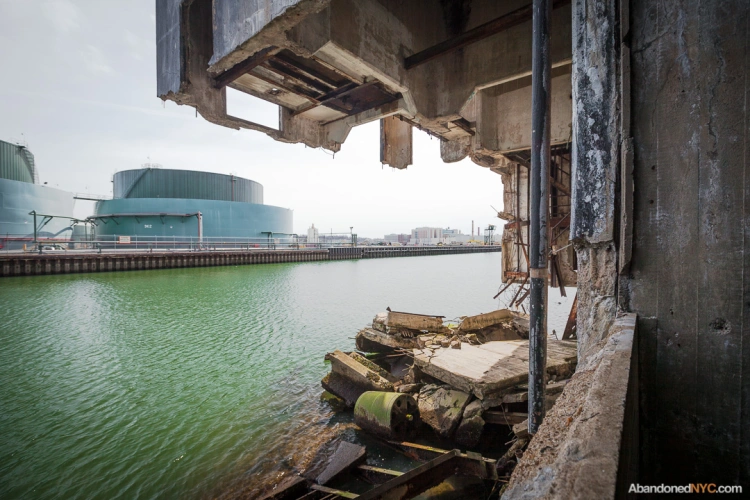

The abandoned McMyler Coal Dumper in Port Reading, NJ

There’s a stretch of the Arthur Kill between Rossville, Staten Island and Port Reading, New Jersey that’s something of an abandoned wonderland. From the New Jersey side, the horizon is dominated by the twin natural gas tanks of Chemical Lane, and the famous Staten Island Boat Graveyard is plainly visible just across the water. But towering over the scene is a structure that rivals both with its staggering beauty and power—the McMyler Coal Dumper.

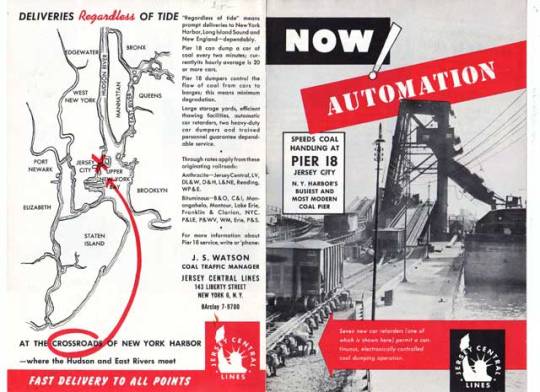

Actually, it would be more accurate to call it a McMyler Coal Dumper. It was one of many nearly identical structures built on the shores of the New York Harbor in the early-to-mid 20th century, including two on Pier 18 in Jersey City. But the Port Reading site is notable for being the last one standing in the New York area. It was constructed in 1917, making it 99 years old at the time of this post.

A 1957 ad for Pier 18 in Jersey City, which boasted two “Big Mac” McMyler Dumpers.

In a vast regional network of coal mines, breakers, railroads, and manufacturing hubs, these machines provided a vital link that helped fuel New York’s industrial age, transferring massive amounts of coal brought by rail from Pennsylvania and the Alleghenies into ships entering the harbor. A McMyler Dumper could unload a 72-ton car of coal every two and a half minutes, operating on a continuous loop for maximum efficiency.

Upon entering the pier, railroad “hoppers” carrying a full load of coal would be pushed up a ramp with a mechanism called a barney. Once in position at the base of the tower, the entire car and its contents would be lifted up on an unloading platform and tilted at 120 degrees, spilling the coal into an enormous “pan,” which funneled the material through an unloader chute and into the holds of outgoing barges. Once empty, the car would be lowered and pushed onto a kickback trestle by the next car in the line-up. These rails looked very much like a roller coaster, and they worked in a similar fashion, using the power of gravity to propel empty cars off of the pier and into the rail yards beyond. The contraption required twelve men to operate, and the work was risky. The brute force of the machine claimed many lives and limbs over the years.

A braver soul would have climbed the tower, but I was satisfied with the view from the pier.

The design stood the test of time, and the pier operated for over 60 years with nearly uninterrupted use (a fire caused considerable damage in 1951, but the unloader was quickly rebuilt.) With demand for coal declining, the machine dumped its last load in the early 80s, and has been steadily deteriorating ever since. Though there has been interest in designating the structure an historic site, its location on private property in an active industrial area has made it an unlikely candidate, and the cost of restoring or moving the structure would be prohibitive, to put it mildly. Unless new industrial development threatens the site, it will likely remain a picturesque ruin for another century before eventually collapsing into the Kill and vanishing into the muck.

That is lucky for the throng of Canada Geese who’ve made a surreal home out of the hulking relic. Though they’re nice to look at, I’ve never had a pleasant encounter with these creatures, and have been charged at by enough of them on the remote shores of the outer boroughs to know they mean business. This time around they were content to squawk and hiss their disapproval from a distance, but I would advise everyone to stay far away during nesting season, which is right around the corner.

The self-appointed guardians of the coal dumper.

A pair of steam engines inside the machine room powered a cable drum…

…which controlled the “barney,” a mechanism used to push cars onto the unloading platform.

These cable drums raised and lowered the unloading platform. Much of the machinery has been removed by scrappers over the years.

The place has a fair amount of graffiti, some quite old. Kaleen’s protestation on the upper right was particularly endearing.

A derelict ferry boat sinks into the Kill on an adjacent pier.

The pan and chute, pictured here, were left in an upright position until Hurricane Irene sent them crashing onto the pier below in 2011. An operator would have sat in the little chamber on the right. A pair of abandoned gas tanks in Rossville, Staten Island can be seen on the horizon.

Low Tide at the McMyler Coal Dumper.

You can see (a model of) a McMyler Coal Dumper in action in the following video:

Inside the Brooklyn Army Terminal

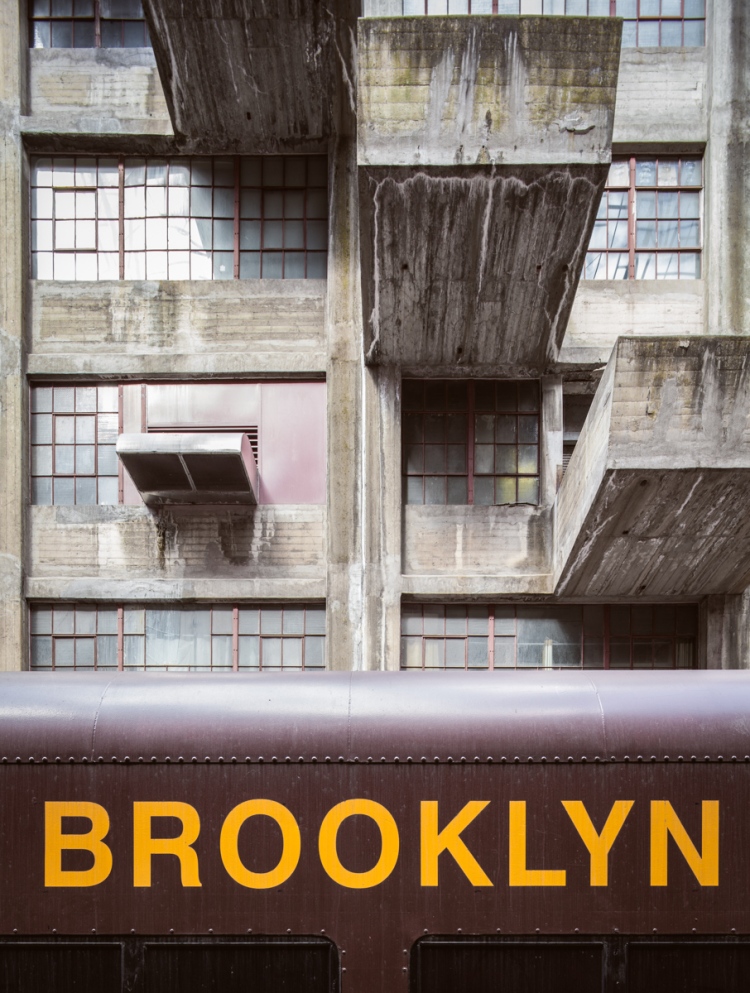

The Brooklyn Army Terminal’s Building B stretches toward the horizon.

Let me be the first to point out that the Brooklyn Army Terminal is far from abandoned. It’s actually one of the most vibrant hubs of industry remaining on a Brooklyn waterfront that was once dominated by factories, warehouses, and refineries, many of which have fallen into decay or been renovated into luxury condos. Along with the Brooklyn Navy Yard, the neighboring Bush Terminal, and nearby Industry City, the Army Terminal is proving every day that industry can not only survive, but thrive, on the Brooklyn waterfront.

I’m often asked why abandoned buildings in New York aren’t just turned into housing for the homeless, offered up to local artists, or repurposed as museums, and the truth is it’s never, ever that simple. But here’s an example of a historic building that has been painstakingly brought back from the brink of decay–over a period of 35 years with $150 million in public and private investment–to become a viable source of job creation. Luckily, the Brooklyn Army Terminal has managed to retain a palpable connection to its history, and in some areas, a pleasing patina of decay in keeping with its old age.

At almost 100 acres, the property covers the length of several city blocks.

Overall, the structure reflects the austerity and efficiency one might expect given its military origins, and sure enough, nearly every architectural embellishment turns out to serve a practical purpose. Seemingly decorative studs lining the top of the facade actually function as a simple but effective drainage system for the roof. It’s a testament to the genius of its architect that such a utilitarian building can attain such elegance. The designer, Cass Gilbert, is best known for masterminding some of New York’s most beautiful and ornate structures, like the iconic Woolworth Building or the majestic Customs House, not to mention the U.S. Supreme Court in Washington, DC.

The construction of the Brooklyn Army Terminal began in 1918 under the direction of the federal government, with the goal of establishing a more efficient means of dispatching supplies and personnel to military fronts around the world. The four million sq ft complex of warehouses, offices, piers, and railroads was built over a period of only 17 months. Though the First World War had ended by the time the structure was completed, the Terminal proved indispensable during WWII, employing over 20,000 military personnel and civilians. It acted as the headquarters of the New York Port of Embarkation, which collectively moved 3.2 million troops and 37 million tons of supplies to army outposts around the globe during the war. Hundreds of thousands of men passed through the terminal on their way to serve overseas, arriving by trains that dropped them off a few paces from the ramps of outgoing ships. The most famous visitor was Elvis Presley, who stayed longer than most, holding a press conference in front of a crowd of photographers, reporters, and fans before embarking on an 18 month tour of Germany in 1958. He had been drafted the previous year.

The Terminal’s design was easily adapted to a variety of uses in peace time. During prohibition, it warehoused confiscated liquor from NYC speakeasies, and after the facility was decommissioned in 1966, the USPS moved operations into the ground floor following a fire in a prominent Manhattan branch. But through much of the 60s and 70s, the facility fell into a period of decay and decline. Ownership transferred to the city of New York in 1981, and the monumental task of restoring the structure for modern industrial use began in earnest when the NYC Economic Development Corporation stepped in to manage the building.

The job was split into discrete stages, tackling one section of the massive complex at a time. An upcoming renovation project dubbed “Phase 5” will complete the restoration of the two largest structures by revitalizing the last 500,000 sq ft of Building A, thanks to a $100 million dollar grant from the De Blasio administration announced last May. Today the leasable space boasts a 99% occupancy rate, with a diverse list of tenants including furniture builders, jewelry makers, and chocolatiers.

If you’re lucky enough to pay a visit, the highlight of the trip is Building B’s jaw-dropping atrium. (It’s generally closed to the public, but Turnstile Tours and Untapped Cities offer regular guided tours.) Freight cars would pull directly into the building and unload supplies with a five ton moveable crane that traveled the atrium from end to end, spanning the length of three football fields. Now the area serves as a walkway for tenants, and loading docks have been repurposed as balconies and container gardens. Recently, the location has been wildly popular for film and photo shoots, which is no surprise. It’s one of the most remarkable interiors in all of New York City.

Book stuff is starting to wind down, but I do have a couple events on the horizon for anyone interested in attending. As always, you can pick up a signed copy directly through me at this website, it’s the best way to support what I do.

Coming Up:

Brooklyn Brainery, April 15th 8:30-10:00, $7(Sold Out)- Mid-Manhattan Library, May 7th, 6:30-8:00, Free!

Beyond NYC: The St. Nicholas Coal Breaker

The daunting exterior of the St. Nicholas Coal Breaker.

In rural eastern Pennsylvania, the coal-rich soil blackens boots, pantlegs, elbows, and faces, covering the densely packed row houses of Mahanoy City with a dingy gray patina. Coal production is still plugging along here, but the lifeblood of this industry town has slowed to a trickle since the 1920s, and the population has followed suit, thinning out to a quarter of its peak residency, back when a few belts of precious anthracite coal 400 million years in the making transformed this backwoods region into a flourishing center of industry. Around a bend on a back road, thousands of shattered window panes gape like jack o’ lantern teeth from the old St. Nicholas Coal Breaker, which has stood for 50 years as a haunting reminder of the town’s better days.

A control room was crawling with hundreds of ladybugs and streaked with white bird droppings.

The region’s coal deposits were first discovered in the late 1700s and the mining industry quickly grew to dominate the area. Soon, the onset of the industrial revolution spurred the region into a mining frenzy, fueled by an influx of European immigrants who settled in the years following the Civil War. The coal found in this corner of Pennsylvania was of the rare “anthracite” variety, which was prized for its purity, burning longer than other types. It’s no wonder they call it “black diamond.” On the grounds of St. Nicholas, where surface mining still goes on, the coal underfoot gives off an iridescent gleam.

A dark corridor on the plant’s second floor gives way to views of the rail yard.

Old work boots have been lovingly arranged by previous visitors to the “boot room.”

The St. Nicholas Breaker was constructed in 1930 on the site of the St. Nicholas Colliery, which earned its name when it first opened on Christmas Day in 1861. That structure was torn down to make way for the new St. Nick, which was the largest coal breaker in the world at the time. With 3,800 tons of steel and a mile and a half of conveyer lines, the monumental machine was capable of churning out 12,500 tons of coal in a single workday.

Raw coal was imported from a number of local mines, where the material was cleaned and crushed before being shipped to St. Nicholas’ storage yards. Here, it awaited an eight story journey up a vertiginous conveyor belt, where it would commence its wild ride through the breaker. It took 12 minutes for the material to pass through the many industrial processes housed inside the plant to prepare the coal for consumption. Demand steadily decreased though the 1950s as alternative energy sources grew in popularity, and the breaker closed down in 1963 after thirty years of production. Ten years later, it was replaced by a modern facility located a half-mile away.

Enormous “hoppers” funneled coal through the breaker.

The factory was constructed with 3,800 tons of steel.

Wooden molds left on the top floor were used to manufacture new parts for the plant.

A dimly lit control room is situated near the end of a gigantic conveyor.

Fifty years on, the interior is surprisingly untouched and structurally sound, with very little graffiti to speak of. Its construction is dizzyingly complex, leaving the untrained eye to marvel at its design without fully comprehending the vast labyrinth of tightly packed machinery. Sadly, this awe-inspiring piece of history may not be long for this world. Partial demolition has already claimed a hefty wing of the structure, and it’s unclear how long the rest of the breaker will remain standing.

Coal dust covers the interior of the St. Nicholas Breaker in Mahanoy City, PA.

When the wind bellows through the St. Nicholas Breaker, ancient drifts of airborne coal dust sting the eyes, clog the throat, and powder the hair, catching the light to lovely effect, if you can stomach the black lung… Back home in Brooklyn I wasted no time getting into the shower to scrub off the day’s dirt, pondering the depth of history in all things. Fossilized remains of Paleozoic plant life pooled at my feet in black clouds, wrenched from the bowels of the earth only to languish in an abandoned factory for half a century and wind up here, spiralling down my bathtub drain to new frontiers. Later that night, I reached for a tissue and winced as a fresh deposit of grade-A anthracite coal expelled from my nose in a thick black mucus. It seemed that a part of St. Nicholas would stay with me forever.

A shaft of light materializes as dust drifts through the breaker at day’s end.

The remains of the St. Nicholas Coal Breaker.

St. Nick was located within the southern section of Pennsylvania’s anthracite coal region.

The St. Nicholas Coal Breaker photographed in 1971.

The Red Hook Grain Terminal

On foggy mornings, nothing can rival the Grain Terminal’s spectral allure.

It’s been nearly fifty years since a freighter docked at the Red Hook Grain Terminal; now black mold overspreads its concrete silos like a mourning veil.

Its origin can be traced to the turn-of-the-century construction of the New York State Barge Canal, which widened and rerouted the Erie Canal at great expense to facilitate the latest advances in shipping. By 1918, New York City was lagging behind in the nation’s grain trade, and the canal was failing, operating at only 10% of its capacity. A new facility was built in the Port of New York to invigorate the underused waterway—a state-run grain elevator in the bustling industrial waterfront of Red Hook, Brooklyn.

The structure is largely composed of 54 circular silos with a combined capacity of two million bushels. Grain was mechanically hoisted from the holds of ships, elevated to the top of the terminal, and dropped into vertical storage bins through a series of moveable spouts. When a purchase was made, the force of gravity would release the grain from the bins, at which point it was elevated back to the top of the terminal and conveyed to outgoing ships.

A shallow puddle makes an effective reflecting pool after a downpour, in keeping with the monumental atmosphere of the place.

Packed with rows of white columns, the ground floor resembles an ancient house of worship.

Red Hook’s grain elevator is one of many similar structures built across the country in the 1920s, most notably in Buffalo, NY. Guided by practical concerns and the laws of nature, American engineers had arrived at a new style of architecture, making a lasting impression on European architects. In Toward an Architecture (1928), Le Corbusier called the American elevators “the first fruits of a new age.” Their influence can be traced through the Brutalist movement of the 50s and 60s, through which inexpensive, unadorned cement structures dominated post-war reconstruction in Europe.

The Grain Elevator was an engineering marvel, but never became a commercial success. The structure quickly became obsolete in the mid-20th century as grain trade in the Port of New York steadily declined from 90 million bushels a year in the 1930s to less than 2 million in the 1960s. Contractors grew to avoid the New York Harbor, where the cost of unloading grain came to three to four times the rate of competing ports in Baltimore, Philadelphia, and New Orleans, largely due to local union restrictions.

The Grain Terminal was emptied of its last bushel in 1965.

The collapse of the grain trade made up a small part of an overall decline along Red Hook’s industrial waterfront in the second half of the 20th century as shipping methods evolved and moved elsewhere. When the jobs dried up, much of the area cleared out, leaving a slew of vacant warehouses and decaying docks. In the year 2000, most of Red Hook’s 10,000 residents lived in the Red Hook Houses, one of the city’s first public housing projects. The development was a notorious hotbed for crack cocaine in the 80s and early 90s, but conditions have gradually improved over the years. A near complete lack of major subways and buses stalled gentrification in the neighborhood, but signs are becoming more common. Today, Van Brunt Street is scattered with specialty wine bars, cupcake shops, and craft breweries, and a big box IKEA store opened in 2007 on the site of a former graving dock.

The Grain Terminal has been the subject of a number of reuse proposals over the years, but none of the plans have amounted to real progress at the site. The building sits on the grounds of the Gowanus Industrial Park, which currently houses a container terminal and a bus depot, among other industrial tenants. The owner is now seeking approval for a controversial plan to extend his property into the bay with landfill, using a concoction of concrete and toxic sludge dredged from the floor of the Gowanus Canal.

As battles wage over the future of the property, the Red Hook Grain Terminal hovers over the Henry Street Basin like a grieving ghost on a widow’s walk, watching for ships that will never return…

A word to the wise: the grounds of the Grain Terminal are patrolled by security, and they’re cracking down on trespassers.

Moveable spouts delivered grain to individual silos.

A 90-foot staircase of corroded metal slats connects the first floor to the top of the storage bins.

The lower levels of two out of three staircases have collapsed into the basin…

Whole sections of the building are on their last legs…

..crumbling into the canal like a latter-day House of Usher.

The building is topped by a small tower on the north end…

…and a larger structure to the south.

The top floor is strewn with manhole-sized apertures, which give way to the mind-numbing vacuum of the empty grain silos.

Looking down these is like staring into the face of death.

It’s a looooong way down.

The Yonkers Power Station, Knocking at the “Gates of Hell”

Take a northern train to Yonkers and watch New York City’s urban sprawl give way to the unspoiled undulations of the Hudson River Valley. You’ll be reminded once again that Manhattan is an island, bounded and formed by three rivers, and there is, in fact, a world outside of it.

One of the stranger stops along the Hudson line can’t be missed; it’s dominated by a sight nearly as impressive as the station you came from. Abandoned since the late sixties, the old power plant at Glenwood may be decidedly more ghoulish than Grand Central Terminal, but it’s almost as grand—they were dreamed up by the same architects. Once, the imposing brick edifice embodied New York City’s ever-increasing industrial prowess, but today, the riverside relic stands as a monument to obsolescence, caught in a destructive contest with the tides.

The Yonkers Power Station was completed in 1906 to enable the first electrification of the New York Central Railroad, built in conjunction with the redesign of Grand Central Terminal. The plant served the railroad for thirty years, but it soon became more cost-effective for the company to purchase its electricity rather than generate its own. Con Edison took over in 1936, using the station’s titanic generating capacity to power the surrounding county. By 1968, new technologies had replaced Glenwood’s outdated turbines, and the station was abandoned.

The Hudson River once delivered raw materials to the powerhouse, but now its waters collect in stagnant pools on the lowest level. Rust has consumed the factory from the inside out; in places, the corrosion is almost audible. Joints creak, bricks topple, ceilings drip, commingling with the constant suck of viscous mud underfoot. Most of the machinery was carried out long ago, leaving only a hulking shell rimmed with staircases, walkways, and ladders—harrowing paths to nowhere.

Some of the rusted-through steps threaten to crumble at the slightest touch, giving way to a thousand foot drop through decaying metal that could land you muddied and bloodied on the swampy first floor. I can’t say it’s worth the risk, but the Grand Canyon views from the plant’s highest reaches can sure ease your mind after a nail-biting ascent. Photographers, urban explorers, and filmmakers flock here; it’s the grandeur in this decay that draws so many, and makes this place worth saving.

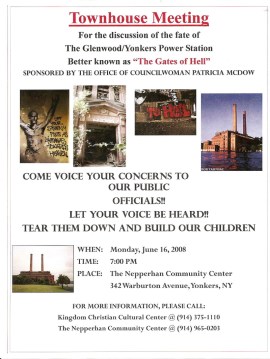

In 2008, Jim Bostic of the Yonkers Gang Prevention Coalition and councilwoman Patricia McDow alleged that the abandoned building was the site of brutal gang initiations, involving some 300 individuals at a time, where savage beatings and sexual deviancy took place on a shocking scale. They called for the immediate demolition of the Glenwood Power Station, referring to it by its well-established nickname, the “Gates of Hell.”

The stories were thrilling, hysterical, and ultimately hard to believe. No evidence was found and no witness stepped forward that could verify the widely-publicized allegations, and the Yonkers Police Department denied having knowledge of any gang-related activities at the site.

The initiative gained the support of a number of locals, but many remained skeptical of McDow, who’s been criticized in the past for overlooking the rising tide of violent crime in her district. Demolishing this historic structure would have little to no effect on neighborhood violence, but as a symbolic gesture, it could appeal to voters.

The powerhouse was spared from the whims of city politics, but it’s technically still at risk; landmarking efforts have failed since a proposal was first put forth in 2005.

It’s been four years since the Glenwood Power Station made headlines as the “Gates of Hell,” but not much had changed there until recently. A new owner spruced up the grounds, removing overgrowth on the lot and clearing ivy from the buildings’ exteriors. It’s a sign of good things to come, though no plans for renovation have been released at this time.

I came to Yonkers a few months prior to the cleanup, unaware that the space had already been booked for a post-apocalyptic webseries shoot. The crew was friendly and professional, but their presence proved a distraction. As a buxom actress screamed “There’s no way out!” for the fifth time, the Yonkers Power Station was stripped of its mystery, seeming to wear its decay with reluctant resignation. Today, it’s a creepy backdrop for zombie films, the subject of gruesome rumors, but it was designed to inspire pride, not fear.

Sites like these are quickly becoming a contentious part of the post-industrial American landscape, scattered remnants of a period of enormous change—a revolution that’s led us, for better or worse, to where we are now. In Yonkers, one such building wades on the banks of the Hudson, its skeleton blushing to shades of orange. It’s an eyesore, a piece of history, and a community threat; also a nice spot to play hooky, take pictures, or build a shopping mall. No one can seem to agree on these “Gates.” So what the Hell should we do with them?

–Will Ellis

Continuing down the hallway. On the lower right, you can see a metal barrel that’s almost completely rusted through.

In Gowanus’ Batcave, Broken Teenage Dreams Live on

Not long ago, a pack of teenage runaways lived the dream in Gowanus’ infamous Batcave, shacking up rent-free in an abandoned MTA powerhouse on the shore of the notoriously toxic Gowanus Canal. Out of the grime, in back rooms and crooked halls, the artifacts of this sizable squatter settlement remain to enlighten, amuse, and unnerve the intrepid few that enter the disreputable interior.

The old Central Power Station of the Brooklyn Rapid Transit Company was built in 1896 to serve a rapidly expanding subway system in the outer boroughs, positioned on the banks of the Gowanus Canal to ensure an efficient intake of coal to power an arsenal of 32 boilers and eight 4,000 horsepower steam-driven generators. The plant’s technology couldn’t keep up with the times, and after a brief second life as a paper recycling plant, the powerhouse was abandoned. Today, it’s more commonly known as the “Batcave,” supposedly named for the creatures that once congregated in its broken-down ceiling.

In the early 2000s, a colony of homeless young people settled inside the building, establishing a thriving, peaceable community. At onset, the squat held a positive reputation, kept under the watchful eye of a few individuals who ensured hard drugs and detrimental criminal activities were kept out. After a drunken rooftop incident, authorities were notified and made their first attempt to evict the punk-rock squatters, leaving the colony without its guardians.

Over the next two years, heroin use and overdose grew rampant, and a wave of brutality overwhelmed the Batcave. Drug-induced violence culminated in a series of nightmarish events; one homeless man was thrown from a window, another overdosed and was left on the street for law enforcement to find. Frightened community members saw to it that the Batcave colony was ousted indefinitely in 2006.

The residents are long gone, but most of their humble furnishings remain. Some living quarters, fashioned in old corner offices of the power plant, are generously sized, complete with beds, bookshelves, and lounge chairs. Others are no larger than a closet; album covers, skulls and superheroes, and a general state of chaos are prominent features of these impromptu bedrooms.

Prized possessions—a VHS copy of the Nightmare Before Christmas, a dogeared paperback edition of Hamlet—molder in the damp with shampoo bottles, plastic toys, and stockpiles of hypodermic needles. Stuffed animals are the most abundant, and telling artifacts. Once treasured, these hulking teddy bears, leather-clad Elmo dolls, and freaky Fisher-Price robots lie mired in filth, decapitated or gutted and hung from strings.

While large-scale pieces by notable graffiti artists dominate the Batcave’s main hall, the more intriguing artworks can be found on the bedroom walls. Always obscene, typically humorous, and occasionally clever, these amateur scrawls portray a community of fun-loving, hard-living, creative youth, although some inscriptions tend toward the dark and morbid, pointing to a deep resentment for society and obsessions with dying and suicide.

It’s no wonder so many lost souls found solace here—just look up. The Batcave’s eye-popping top floor certainly feels like a sanctuary. Light rain filters down from a collapsed ceiling, atomized to a sweeping mist. In a permanent puddle, arched reflections of the clerestory windows tremble. Pleated ceiling panels once muffled the hum and hiss of a mammoth industrial undertaking, but their effect is more visual now. Interweaving supports shimmer like the facets of a diamond as you move through the space—it’s a crustpunk kaleidoscope that constitutes one of the most spectacular abandoned sights in New York City.

For all the atmosphere of grime and decay, the Batcave gives an impression of a living space that, though not well kept, was certainly well loved. It isn’t difficult to imagine a time when this damp industrial shell was filled with warmth and welcome, or to imagine its occupants, in those first idyllic months, brimming with a sense of ownership and control, invulnerable to the pressures of parents and policemen.

The fate of the Batcave lies in the balance of Gowanus’ contentious transition from industrial wasteland to trendy residential neighborhood. Numerous plans have emerged for the development of the property, but the canal’s recent Superfund designation and an uncertain future for the game-changing Whole Foods development across the street has deterred potential investors from shelling out the millions necessary to renovate the structure and rehabilitate its environmentally hazardous grounds. Through an overgrown lot in the height of Spring, the dilapidated redbrick facade remains a sight to behold, concealing a sordid wonderland within, marking the spot where a youthful dream lived, and died.

-Will Ellis

UPDATE Nov 23, 2012: The Batcave property sold for $7 million to philanthropist Joshua Rechnitz. The building will be saved, and renovated into art studios and exhibition space. Read the New York Times article here.

Some rooms are relatively undisturbed. Couldn’t resist lighting this candle holder, fashioned out of a beer can.

A neighboring storage facility reflects its gawdy plastic siding into a Batcave nook, accenting some interiors with splashes of orange and blue.

Inside The Domino Sugar Refinery

Situated on an eleven-acre parcel of waterfront in the shadow of the Williamsburg Bridge, the derelict Domino Sugar Refinery remains one of the most recognized monuments of Brooklyn’s rapidly disappearing industrial past. Now, after a decade of false starts, new plans for a modern, mixed use megacomplex may put an end to the decaying colossus that was once the largest refinery in the world, marking the final passage of a working-class Williamsburg.

In the late 19th century, Brooklyn was responsible for over half of the country’s sugar production, with Havemeyers & Elders Sugar Company leading the pack of over 20 major refineries that called the borough home. The factory’s signature building—a towering redbrick structure that still stands today—was constructed in 1884 to replace an older sugarhouse that had been destroyed in a catastrophic fire. Three years later, 17 of the largest sugar refiners in the U.S. merged to form the Sugar Refineries Co. Trust, later reorganized as the American Sugar Refining Co., and branded as Domino Sugar in 1902. Domino and its predecessors operated on the waterfront for a total of 148 years; at its peak, the site employed over 5,000 workers, capable of producing over three million pounds of processed sugar a day.

The American Sugar Refinery Processing House shown after its completion in the 1880s.

With the growing use of high fructose corn syrup and artificial sweeteners came a steady decline in demand for old-fashioned cane sugar. Production at the Williamsburg plant ended in the early 2000s with partial packaging operations lingering until 2004. The non-profit Community Preservation Corporation purchased the Domino site the same year for $58 million. Their plan would preserve and renovate the central refinery building, landmarked in 2007, and raise a battalion of architecturally offensive residential high-rises in the footprint of the surrounding industrial complex, razing the Raw Sugar Warehouse, constructed in 1927, and the Packaging House, a 1962 addition, in the process.

The old “New Domino” complex.

Two Trees teamed up with noted NYC firm SHoP Architects—the group is already leaving a lasting impression on the city landscape with the Barclay’s Center and the East River Esplanade. Unveiled Friday, their monumental plans seem tailor-made to appease the new population of Williamsburg, without limiting profits.

The plan is similar in scope to the vision of the CPC, with several key improvements. The buildings rise higher—up to 60 stories—to allow for more park space, including a one-acre “Domino Square,” where builders envision film screenings and outdoor concerts. Some of the structures include open spaces and sky bridges, an innovative solution sought to preserve harbor views for the inland community. The landmarked refinery building would be preserved and converted to office space, and several pieces of machinery would be salvaged for inclusion in a public “artifact walk.” In the face of such monumental changes, this may be of some consolation to New York nostalgics.

Developers are working with the YMCA to establish a community space on the site, and are also proposing a new public school. Street level retail would favor independent business over chain store tenants. Two Trees also intends to deliver on the previous developer’s promise of 660 units of “affordable” housing, though the condition was never legally binding.

With all these benefits, Two Trees is attempting to pacify a community that is weary of change, and concerned for its future. The Domino development marks a clear and dramatic manifestation of a contentious transition that’s been taking place in Williamsburg for the last decade. The area is well known today as an infamous haven for hipster youth, but 10 years ago the neighborhood was a quiet, working-class community of Jewish, eastern European, and Hispanic immigrants. Now, it won’t be long before the tattooed and the trendy are priced out, leaving room for only the wealthiest New Yorkers. Emerging across formerly affordable areas of Manhattan and Brooklyn, the familiar pattern is destined to change the face of our city. Call it progress or gentrification. Praise the plans, or lament the loss, there’s no stopping the reckless growth of New York City.

In its final moments, the Domino Sugar Refinery slips further into a speedy decay, introducing an element of the exotic to an already unfamiliar environment. Some of the alien interiors are coated with shallow puddles of tar, or dark sugar byproducts rendered the consistency of glue, or apple crisp. Others take on the appearance of an Egyptian temple in the impenetrable darkness, with row upon row of columns supporting the chasm of a vacant warehouse. Tinged aquamarine, the peeling factory floors of the packaging plant might be confused for the barnacled mechanisms of a sunken ship. The complex is unnervingly immense, presenting a seemingly endless series of floors connected by lightless, labyrinthine staircases. Alone in a factory that once employed thousands, up against its unfathomable depths, it felt like being in the belly of the whale—it didn’t take a miracle to get me out of there.

The next time you ride down the FDR or traverse the Williamsburg Bridge, take a good look at the sprawling industrial giant that was the Domino Sugar Refinery; it won’t be long before it’s preened and polished into the marketably modern new New Domino—another of the city’s rough edges, smoothed over in favor of gleaming glass.

Shedding Light on a Forgotten Red Hook Warehouse

Two stark, imposing sister buildings at 160 and 62 Imlay St. tower over the industrial wastes of Red Hook, Brooklyn. One recently renovated into a high-tech Christie’s storage facility for multi-million dollar works of art, the other a hulking, empty shell, waiting for a second life.

Constructed in 1911-13, the identical twin loft buildings on 160 and 62 Imlay St. began their lives as storehouses for the New York Dock Company. They made up a small part of a “globe-encircling commercial undertaking,” which included a sprawling network of 200 warehouses, 39 piers, and three ship-to-rail freight terminals extending over three miles of the Brooklyn Waterfront.

Rapidly declining profits and outdated infrastructure resulted in a cessation of operations in 1983. The buildings were purchased by a developer in 2000 and 2002 for a combined 22 million. In 2003, plans for a residential overhaul of 160 Imlay fell through as a result of a lawsuit from the local Chamber of Commerce, which sought to retain an industrial use for the property.

Now at 62 Imlay St, floors once flooded with tobacco and cotton are welcoming a new set of residents—multimillion dollar works of art by the likes of Van Gogh, Brancusi, and Pollack. The facility is leased by the high-profile auction house Christie’s and is equipped with “infrared video cameras, biometric readers and motion-activated monitors, as well as smoke-, heat- and water-detection systems.”

Adjacent sits the other sister with an uncertain future, its broad, vacant interiors shielded with plastic and shrouded in black netted scaffolding, gutted in preparation for a rumored second attempt at a residential conversion.