AbandonedNYC

yonkers

Green Thumbing Through the Boyce Thompson Institute

The abandoned Boyce Thompson Institute in Yonkers.

In 1925, Dr. William Crocker spoke eloquently on the nature of botany: “The dependence of man upon plants is intimate and many sided. No science is more fundamental to life and more immediately and multifariously practical than plant science. We have here around us enough unsolved riddles to tax the best scientific genius for centuries to come.”

As the director of the Boyce Thompson Institute in Yonkers, Crocker was charged with leading teams of botanists, chemists, protozoologists, and entomologists in tackling the greatest mysteries of the botanical world, focusing on cures for plant diseases and tactics to increase agricultural yields. The facility was opened in 1924 as the most well equipped botanical laboratory in the world, with a system of eight greenhouses and indoor facilities for “nature faking”—growing plants in artificial conditions with precise control over light, temperature, humidity, and carbon dioxide levels.

The sun sets on the greenhouses of the Boyce Thompson Institute.

The institution had been founded by Col. William Boyce Thompson, a wealthy mining mogul who became interested in the study of plants after witnessing starvation while being stationed in Russia, (although an alternate history claims he just loved his garden.) Recognizing the rapid rate of population growth worldwide, he sought to establish a research facility with an eye toward increasing the world’s food supply, “to study why and how plants grow, why they languish or thrive, how their diseases may be conquered and how their development may be stimulated.”

By 1974, the Institute had gained an international reputation for its contributions to plant research, but was beginning to set its sights on a new building. The location had originally been chosen due to its close proximity to Col. Thompson’s 67-room mansion Alder Manor, but property values had risen sharply as the area became widely developed. Soaring air pollution in Yonkers enabled several important experiments at the institute, but hindered most. With a dwindling endowment, the BTI moved to a new location at Cornell University in Ithaca, and continues to dedicate itself to quality research in plant science.

Most of the interiors had a near-complete lack of architectural ornament, but the entryway was built to impress.

The city purchased the property in 1999 hoping to establish an alternative school, but ended up putting the site on the market instead. A developer attempted to buy it in 2005 with plans to knock down the historic structures and build a wellness center, prompting a landmarking effort that was eventually shot down by the city council. The developer ultimately backed out, and the buildings were once again allowed to decay. Last November, the City of Yonkers issued a request for proposals for the site, favoring adaptive reuse of the existing facilities. Paperwork is due in January.

Until then, the grounds achieve a kind of poetic symmetry in warmer months, when wild vegetation consumes the empty greenhouses, encroaching on the ruins of this venerable botanical institute…

-Will Ellis

Ornate balusters made this staircase the most attractive area of the laboratory.

A central oculus leads to this mysterious pen in the attic.

This stone sphere had been the centerpiece of the back facade, until someone decided to push it down this staircase. See its original location here.

The city gave up on keeping the place secured long ago.

The north wing had been gutted at some point.

An interesting phenomenon in the basement–a population of feral cats had stockpiled decades worth of food containers left by well-meaning cat lovers.

A view from the upstairs landing was mostly pastoral 75 years ago.

The main building connects to a network of intricate greenhouses.

The interiors were covered with shattered glass, but still enchanting.

The Yonkers Power Station, Knocking at the “Gates of Hell”

Take a northern train to Yonkers and watch New York City’s urban sprawl give way to the unspoiled undulations of the Hudson River Valley. You’ll be reminded once again that Manhattan is an island, bounded and formed by three rivers, and there is, in fact, a world outside of it.

One of the stranger stops along the Hudson line can’t be missed; it’s dominated by a sight nearly as impressive as the station you came from. Abandoned since the late sixties, the old power plant at Glenwood may be decidedly more ghoulish than Grand Central Terminal, but it’s almost as grand—they were dreamed up by the same architects. Once, the imposing brick edifice embodied New York City’s ever-increasing industrial prowess, but today, the riverside relic stands as a monument to obsolescence, caught in a destructive contest with the tides.

The Yonkers Power Station was completed in 1906 to enable the first electrification of the New York Central Railroad, built in conjunction with the redesign of Grand Central Terminal. The plant served the railroad for thirty years, but it soon became more cost-effective for the company to purchase its electricity rather than generate its own. Con Edison took over in 1936, using the station’s titanic generating capacity to power the surrounding county. By 1968, new technologies had replaced Glenwood’s outdated turbines, and the station was abandoned.

The Hudson River once delivered raw materials to the powerhouse, but now its waters collect in stagnant pools on the lowest level. Rust has consumed the factory from the inside out; in places, the corrosion is almost audible. Joints creak, bricks topple, ceilings drip, commingling with the constant suck of viscous mud underfoot. Most of the machinery was carried out long ago, leaving only a hulking shell rimmed with staircases, walkways, and ladders—harrowing paths to nowhere.

Some of the rusted-through steps threaten to crumble at the slightest touch, giving way to a thousand foot drop through decaying metal that could land you muddied and bloodied on the swampy first floor. I can’t say it’s worth the risk, but the Grand Canyon views from the plant’s highest reaches can sure ease your mind after a nail-biting ascent. Photographers, urban explorers, and filmmakers flock here; it’s the grandeur in this decay that draws so many, and makes this place worth saving.

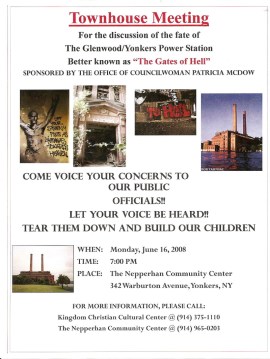

In 2008, Jim Bostic of the Yonkers Gang Prevention Coalition and councilwoman Patricia McDow alleged that the abandoned building was the site of brutal gang initiations, involving some 300 individuals at a time, where savage beatings and sexual deviancy took place on a shocking scale. They called for the immediate demolition of the Glenwood Power Station, referring to it by its well-established nickname, the “Gates of Hell.”

The stories were thrilling, hysterical, and ultimately hard to believe. No evidence was found and no witness stepped forward that could verify the widely-publicized allegations, and the Yonkers Police Department denied having knowledge of any gang-related activities at the site.

The initiative gained the support of a number of locals, but many remained skeptical of McDow, who’s been criticized in the past for overlooking the rising tide of violent crime in her district. Demolishing this historic structure would have little to no effect on neighborhood violence, but as a symbolic gesture, it could appeal to voters.

The powerhouse was spared from the whims of city politics, but it’s technically still at risk; landmarking efforts have failed since a proposal was first put forth in 2005.

It’s been four years since the Glenwood Power Station made headlines as the “Gates of Hell,” but not much had changed there until recently. A new owner spruced up the grounds, removing overgrowth on the lot and clearing ivy from the buildings’ exteriors. It’s a sign of good things to come, though no plans for renovation have been released at this time.

I came to Yonkers a few months prior to the cleanup, unaware that the space had already been booked for a post-apocalyptic webseries shoot. The crew was friendly and professional, but their presence proved a distraction. As a buxom actress screamed “There’s no way out!” for the fifth time, the Yonkers Power Station was stripped of its mystery, seeming to wear its decay with reluctant resignation. Today, it’s a creepy backdrop for zombie films, the subject of gruesome rumors, but it was designed to inspire pride, not fear.

Sites like these are quickly becoming a contentious part of the post-industrial American landscape, scattered remnants of a period of enormous change—a revolution that’s led us, for better or worse, to where we are now. In Yonkers, one such building wades on the banks of the Hudson, its skeleton blushing to shades of orange. It’s an eyesore, a piece of history, and a community threat; also a nice spot to play hooky, take pictures, or build a shopping mall. No one can seem to agree on these “Gates.” So what the Hell should we do with them?

–Will Ellis

Continuing down the hallway. On the lower right, you can see a metal barrel that’s almost completely rusted through.