AbandonedNYC

Preservation

Talking Trash in Dubos Point Wildlife Sanctuary

Take the A train past JFK. You’ll be one of a handful of travelers left on a car that seemed well over capacity a moment ago; the babble of the crowd fades to the soft hum of an unimpeded machine. Nobody asks you for money, or directions. If you’ve made it this far, you know where you’re going.

Suddenly, the ground drops out and you’re gliding over the silver Jamaica Bay. The train runs just above sea level, skimming over a surface that teems visibly with diving cormorants. Clustered with skeletal boat frames, aged marinas jut from a neglected shoreline across the water, to the west, a row of painted houses stand on stilts. There’s no place like the Rockaways to experience New York as a city by the sea.

Head east at Hammels Wye, and a brief walk through the quiet neighborhood of Averne will lead you to a little known peninsula called Dubos Point, one of the last fragments of salt marsh left in a city that was once ringed with tidal wetlands. The marsh was filled with dredged materials in 1912 in preparation for an ill-fated real estate development, but over the last century, the area has reverted to its natural state. In 1988, the land was acquired by the Parks Department, deemed a wildlife sanctuary, and given an official name for the first time (Rene Dubos was a microbiologist and environmental activist who coined the phrase “Think Globally, Act Locally”).

Parks officials envisioned marked nature trails and boardwalks for community use, and planned to build nesting structures and employ part-time patrol staff to encourage wildlife and keep the place clean, but none of this came to be. The Audubon Society of New York maintained the grounds sporadically until 1999, but abandoned its post citing a lack of resources. Since then, the area has been largely neglected, leaving its care up to volunteers. Green Apple Corps and the Rockaway Waterfront Alliance have orchestrated several clean-up events over the years, but they’re facing an uphill battle.

Every day, the shores of Dubos Point are bombarded with an onslaught of garbage, and it’s not coming from park visitors (the preserve is technically not open to the public). Most of the refuse is washed up from the bay, after a long journey through storm drains that began in the littered streets of New York City. Familiar objects are made strange, touched by a long encounter with an invisible world, caked with green algae, eroded with salt, barnacle-burdened and bleached by the sun. The entire peninsula resounds with the constant susurration of wind through grass. For all these reeds are hiding, perhaps they whisper secrets; mud-moored vessels, decaying toys, and saltbored furniture lay half-concealed in the tidal growth.

Standing water in old tires and plastic debris makes for a perfect breeding ground for the area’s most populous species. My first steps onto the grounds of Dubos Point seemed to disturb some ancient curse, as great swarms of mosquitoes rose from their stagnant hollows to draw my blood sacrifice. The Parks department has been criticized in the past for neglecting its duties at Dubos Point while mosquito infestation reached “plague proportions” in the late 90s, rendering backyards unusable from April to October. After years of complaints and little improvement, some residents resorted to building outdoor shelters for brown bats, a natural insect predator. Today, the only visible improvement made on the grounds of Dubos Point is a line of Mosquito Magnet kiosks, placed every 100 feet along the boundary of the preserve.

Despite decades of pollution, the Jamaica Bay harbors hundreds of species of wildlife, and the water is cleaner today than it was 100 years ago. As one of the last remaining pockets of undeveloped land in New York, the estuary supplies an essential resting place for migratory birds along the Atlantic Flyway; egrets, herons, and peregrine falcons are spotted here. Looking past the garbage, you can still make out the natural beauty of Dubos Point, and imagine what this whole region was like 400 years ago. Neck-high cordgrass is abundant, trapping bits of decayed organisms to fuel a thriving, though limited, ecosystem. Throngs of fiddler crabs crowd the soggy ground, scuttling sideways with one collective mind, crunching underfoot like eggshells. The breezy silence is only interrupted by an occasional splash from a jumping fish, or the roar of a plane, taking off from the crowded runways of JFK just across the water. Off the curling tip of Dubos Point, fishermen still cast their lines in the Sommerville Basin, affirming a bond we’ve all but lost.

12,000 of the original 16,000 acres of wetlands around the Jamaica Bay have already been filled in for development, and sources predict that the last of the saltwater marshes could disappear in the next 20 years. It’s a shame to see one of the few protected areas in this condition, when its potential for education and recreation is so apparent. New York needs to protect its wild spaces, and sometimes that means getting our hands dirty. To learn about volunteer opportunities with the Parks Department, visit their website. And check back for information on the next Dubos Point clean-up.

The Yonkers Power Station, Knocking at the “Gates of Hell”

Take a northern train to Yonkers and watch New York City’s urban sprawl give way to the unspoiled undulations of the Hudson River Valley. You’ll be reminded once again that Manhattan is an island, bounded and formed by three rivers, and there is, in fact, a world outside of it.

One of the stranger stops along the Hudson line can’t be missed; it’s dominated by a sight nearly as impressive as the station you came from. Abandoned since the late sixties, the old power plant at Glenwood may be decidedly more ghoulish than Grand Central Terminal, but it’s almost as grand—they were dreamed up by the same architects. Once, the imposing brick edifice embodied New York City’s ever-increasing industrial prowess, but today, the riverside relic stands as a monument to obsolescence, caught in a destructive contest with the tides.

The Yonkers Power Station was completed in 1906 to enable the first electrification of the New York Central Railroad, built in conjunction with the redesign of Grand Central Terminal. The plant served the railroad for thirty years, but it soon became more cost-effective for the company to purchase its electricity rather than generate its own. Con Edison took over in 1936, using the station’s titanic generating capacity to power the surrounding county. By 1968, new technologies had replaced Glenwood’s outdated turbines, and the station was abandoned.

The Hudson River once delivered raw materials to the powerhouse, but now its waters collect in stagnant pools on the lowest level. Rust has consumed the factory from the inside out; in places, the corrosion is almost audible. Joints creak, bricks topple, ceilings drip, commingling with the constant suck of viscous mud underfoot. Most of the machinery was carried out long ago, leaving only a hulking shell rimmed with staircases, walkways, and ladders—harrowing paths to nowhere.

Some of the rusted-through steps threaten to crumble at the slightest touch, giving way to a thousand foot drop through decaying metal that could land you muddied and bloodied on the swampy first floor. I can’t say it’s worth the risk, but the Grand Canyon views from the plant’s highest reaches can sure ease your mind after a nail-biting ascent. Photographers, urban explorers, and filmmakers flock here; it’s the grandeur in this decay that draws so many, and makes this place worth saving.

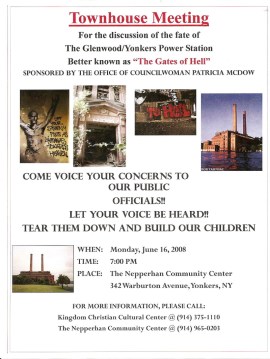

In 2008, Jim Bostic of the Yonkers Gang Prevention Coalition and councilwoman Patricia McDow alleged that the abandoned building was the site of brutal gang initiations, involving some 300 individuals at a time, where savage beatings and sexual deviancy took place on a shocking scale. They called for the immediate demolition of the Glenwood Power Station, referring to it by its well-established nickname, the “Gates of Hell.”

The stories were thrilling, hysterical, and ultimately hard to believe. No evidence was found and no witness stepped forward that could verify the widely-publicized allegations, and the Yonkers Police Department denied having knowledge of any gang-related activities at the site.

The initiative gained the support of a number of locals, but many remained skeptical of McDow, who’s been criticized in the past for overlooking the rising tide of violent crime in her district. Demolishing this historic structure would have little to no effect on neighborhood violence, but as a symbolic gesture, it could appeal to voters.

The powerhouse was spared from the whims of city politics, but it’s technically still at risk; landmarking efforts have failed since a proposal was first put forth in 2005.

It’s been four years since the Glenwood Power Station made headlines as the “Gates of Hell,” but not much had changed there until recently. A new owner spruced up the grounds, removing overgrowth on the lot and clearing ivy from the buildings’ exteriors. It’s a sign of good things to come, though no plans for renovation have been released at this time.

I came to Yonkers a few months prior to the cleanup, unaware that the space had already been booked for a post-apocalyptic webseries shoot. The crew was friendly and professional, but their presence proved a distraction. As a buxom actress screamed “There’s no way out!” for the fifth time, the Yonkers Power Station was stripped of its mystery, seeming to wear its decay with reluctant resignation. Today, it’s a creepy backdrop for zombie films, the subject of gruesome rumors, but it was designed to inspire pride, not fear.

Sites like these are quickly becoming a contentious part of the post-industrial American landscape, scattered remnants of a period of enormous change—a revolution that’s led us, for better or worse, to where we are now. In Yonkers, one such building wades on the banks of the Hudson, its skeleton blushing to shades of orange. It’s an eyesore, a piece of history, and a community threat; also a nice spot to play hooky, take pictures, or build a shopping mall. No one can seem to agree on these “Gates.” So what the Hell should we do with them?

–Will Ellis

Continuing down the hallway. On the lower right, you can see a metal barrel that’s almost completely rusted through.

Inside Fort Totten: Part 1

Fort Totten sits on a far-flung peninsula of the Long Island Sound, forming the Northeast corner of Queens. The grounds of this defunct military installation turned underfunded public park are home to over 100 historic buildings representing a series of changes that have taken place over the area’s quiet 200 year history. Unfortunately, the majority of these stuctures have been disused for decades, and many are in a state of progressive collapse. With so much of Fort Totten closed off with caution tape, overtaken with vines, or hidden beneath rusty fences, it makes for an unconventional park, but a fascinating place to wander.

An 1829 farmhouse predating the land’s military use crumbles behind a weedy barricade; out front, a prominent sign bears the inscription: “Please Excuse My Appearance, I am a Candidate for Historical Preservation.” It’s an image that typifies the current state of affairs in the Fort Totten Historic District.

On the northern tip of Willet’s Point, a monumental granite fortification constructed during the Civil War as a key component of the defense of the New York Harbor sits unoccupied, though it’s used as a haunted house on occasion. Clustered on the rest of the grounds, dozens of dilapidated Romanesque Revival and Queen Anne Style officers’ quarters, hospitals, bakeries, movie theatres, and laboratories vie for restoration, but so far the funding has failed to materialize.

One such building, a two-story YMCA facility built in 1926, has been abandoned for close to 20 years, but much of what’s left behind lies undisturbed. On a bulletin board in an upstairs landing, a 1995 thank-you letter from a kindergarten class at PS 201 hangs by a crude depiction of Santa Claus, both lovingly dedicated to an Officer Rivera. Steps away, in a rotting book room, an incongruous stash of 80s porno magazines.

Most recently used as a community relations unit of the New York City Police Department, the building is cluttered with mattresses, discarded packaging, and unopened toy donations. The New York City Fire Department, which now operates training facilities in a renovation abutting the hospital building, currently uses the attached gymnasium as a storage space. The basement was filled with rusted-through shelving and ruined equipment, flooded and too dark to shoot.

An overgrown pit in a World War I battery.

On the other side of the peninsula, a series of concrete batteries sit half-submerged in plant life. These were constructed at the turn of the century, but by 1938, they were declared obsolete and subsequently abandoned. The boxy design looks like modern architecture to me, but the battery reveals its true age in other ways.

Pencil-thin stalactites ornament the ceiling wherever the rain gets in, suspended over a crank-operated machine designed to lift heavy weaponry a century ago. The network of maze-like tunnels feature arched hallways with metal doors, winding staircases, and yawning pits, all fit for a dungeon. Guards stationed at the fort were laid off in 2009, and it was unclear on my visit if the area was open to the public or not. A rusty barrier, more hole than fence, didn’t keep out a couple of high school kids, but offered a spot for them to park their bikes.

When the military base changed hands in 2005 and became an official New York City Park, Bloomberg predicted that Fort Totten was “certain to become one of New York’s most popular parks.” Some community members feared that the estimated 450,000 yearly visitors would disrupt parking, increase crime, and change the face of the neighborhood, but ten years later, tourism has yet to pose a problem.

Fort Totten hasn’t lived up to its potential just yet, but the progress that has been made gives hope for improvements to come. The park now offers regular events and educational programs to draw visitors and enrich the surrounding community. Several nonprofit groups have occupied and renovated the decrepit buildings, including the landmarked Officers’ Club, which now serves the Bayside Historical Society as an educational facility and exhibition and event space. These are small but significant victories in the effort to save the historic legacy of a little-known plot that could be the crown jewel of Queens parkland.

(Though in some cases, it may be too little, too late. One look inside the profoundly decayed Fort Totten Army Hospital, in Part 2 of this post, will assure you of that.)

-Will Ellis

Related Links:

- Fort Totten Historic District Designation Report

- Fort Totten History from the Bayside Historical Society

- NYTimes 1999 “Fort Totten’s Old Houses are Tottering”

- NYTimes 2003 “Nearer to a Fort Totten Park but Not to a Consensus”

- Scouting NY—A Snowy Day at Fort Totten

This room must have provided temporary housing to minors. The floor was littered with clothing and old English projects.

In the opposite corner, a derelict dollhouse. If I had been in the Twilight Zone, I’d have found a miniature me in there.

Some rooms held a few remnants…