AbandonedNYC

abandoned

Wandering Fort Wadsworth

Battery Weed looms over a desolate shoreline in Fort Wadsworth, Staten Island.

At the easternmost tip of Staten Island, a natural promontory thrusts over the seething Narrows of the New York Harbor, formed by glaciers thousands of years ago. The site’s geography most recently made it a prime location for the Verrazano Bridge, but its history as a popular scenic overlook and strategic defense post dates back to the birth of the nation. The British had occupied the area during the Revolutionary War, and its first permanent structures were built by the state of New York in the early 1800s. These fortifications safeguarded the New York Harbor during the War of 1812, but were abandoned shortly thereafter. So began the familiar cycle of ruin and rebirth that characterizes the history of Fort Wadsworth.

By the mid-19th century, these early structures had fallen into an attractive state of decay. In a time when all of Staten Island held a romantic appeal as an escape from the burgeoning industrialism of New York City, Fort Wadsworth in particular was known for its dramatic terrain, sweeping views of the harbor, and evocative old buildings. Herman Melville described the scene in 1839:

“…on the right hand side of the Narrows as you go out, the land is quite high; and on top of a fine cliff is a great castle or fort, all in ruins, and with trees growing round it… It was a beautiful place, as I remembered it, and very wonderful and romantic, too…On the side away from the water was a green grove of trees, very thick and shady and through this grove, in a sort of twilight you came to an arch in the wall of the fort…and all at once you came out into an open space in the middle of the castle. And there you would see cows grazing…and sheep clambering among the mossy ruins…Yes, the fort was a beautiful, quiet, and charming spot. I should like to build a little cottage in the middle of it, and live there all my life.”

Under the Verazzano Bridge.

The “castle” was demolished to make way for new fortifications constructed as part of the Third System of American coastal defense, known as Battery Weed and Fort Thompkins today. The batteries remain the fort’s most impressive and unifying structures, but they too were deemed obsolete as early as the 1870s due to advances in weaponry, and were used for little more than storage by the 1890s. At the turn of the 20th century, Fort Wadsworth entered yet another phase of military construction under the Endicott Board, when the United States made a nationwide effort to rethink and rebuild its antiquated coastal defenses. Like its predecessors, the Endicott batteries never saw combat, and were essentially abandoned after World War I.

Inside a powder room of Battery Catlin.

A squatter’s unmade bed in the back of the structure.

Though Fort Wadsworth was occupied by the military in various capacities until 1995, its defense structures went unused for most of the 20th century. By the 1980s, woods and invasive vines had covered areas that were once open fields, and Battery Weed was living up to its name, overtaken by mature trees and overgrowth. Since Fort Wadsworth was incorporated into the Gateway National Recreation Area in 1995, its major Third System forts (Battery Weed and Fort Thompkins) have been well maintained and properly secured, and upland housing and support buildings have been occupied by the Coast Guard, Army Reserve, and Park Police. But the headlands still retain an air of abandonment, due in large part to the condition of the Endicott Batteries, which remain off-limits to the public.

Over five of these batteries are scattered across the grounds, all in various states of disrepair.

The Endicott Batteries are filled with narrow, windowless rooms, tomblike hollows, and underground shafts.

Their military blandness stands out in contrast to the grace and grandeur of the fort’s earlier structures deemed worthy of preservation.

Layers of history peel back like an onion at Fort Wadsworth, as evidenced by a new discovery just unearthed by Hurricane Sandy. The storm caused a section of a cliff to collapse, downing several large trees and exposing the entrance to a previously unknown battery. Its vaulted granite construction places it firmly in the Third System, which means it was built around the time of the Civil War. Very little is known about the structure, except that it’s the only one of its kind at Fort Wadsworth. My best guess traces its partial construction to the 1870s, when Congress left many casemated fortifications unfinished by refusing to grant additional funding.

A previously unknown granite battery, possibly dating back to the Civil War, was unearthed by Hurricane Sandy.

Large mounds of soil block the interior of the battery from view.

They’d been sifted through ventilation shafts in the ceiling over decades of burial.

Over the mound, the vaulted structure leads deeper into the ground.

To my disappointment, the next room came to a dead end, and to my horror, it was crawling with hundreds of cave crickets. These blind half spider/half cricket monstrosities pass their time in the darkest, dampest, most inhospitable environments, and are known for devouring their own legs when they’re hungry. They give perspective to the level of isolation of this chamber, which likely stood underground for over a century.

What other mysteries still lie buried in the lunging cliffs of Fort Wadsworth, or the depths of this forgotten battery? The dirt may well conceal deeper rooms and darker discoveries…

Cave crickets in the deepest room of the forgotten battery.

Special thanks to Johnnie for the tip! Get in touch if you know of a historic, abandoned, or mysterious location in the five boroughs that’s worth exploring.

Brooklyn Wild: Gravesend’s Accidental Park

An abandoned boat wades in a narrow cove between Calvert Vaux Park and the vacant lot.

It seems like every square inch of New York City has been categorized, labeled, and filled beyond capacity. But if you know where to look on the fringes of the city, you can still find places without names.

On the waterfront of Gravesend, Brooklyn, such a place still stands. It’s an all but untraveled wedge of vacant land, nestled between aging marinas and the northern border of Calvert Vaux Park on Bay 44th St. It’s a place I can only call “the secret park,” but there’s no mention of it on the department’s website. In its place, the all-knowing Google maps shows only a dull gray transected by the mysterious Westshore Avenue, though no such road exists.

A praying mantis seeks refuge in the tall grasses of the secret park.

The small peninsula was born out of the construction of the Verrazano Bridge in the 1960s when excavated material from the project was deposited on the shore of Gravesend Bay. Most of the new land was incorporated into the existing Drier-Offerman Park, but for some reason, this small finger of land was left out of the plan. Through the 1970s, it served as an illegal junkyard, but by 1982, developers came forward with a plan to construct a seaside residential development at the site. Apparently, the project never came to fruition. The city of New York suggests environmental remediation as a condition for future development.

Concrete construction debris can be found throughout the lot.

The peninsula has few trees aside from these saplings.

The ruins of an old marina rot on the northern edge of the property.

Lush foliage thrives in a wooded section behind the baseball fields of Calvert Vaux Park.

On the north shore of the peninsula, decaying pilings show the outline of a former pier and odd construction debris lie scattered throughout the landscape. A family of squatters lives comfortably out of industrial containers near the lot’s entrance, where a handful of abandoned watercraft comes to the surface at low tide. Beer cans and fire pits point to recent nights of youthful revelry, but by daytime, fishermen flock to this desolate place to cast their lines into the muddy gray waters of Gravesend Bay. At the shoreline, a few minutes of rock flipping will fetch you dozens of small green crabs. On a recent visit, I was amazed to meet two hunter/gatherers harvesting these fruits of the sea by the bucket, though I wasn’t tempted to try one.

I’d wager that it won’t be long before the development potential of the site is realized, but for the time being, the unkempt wilds of the secret park offer a rustic alternative to the paved walkways and manicured lawns of our city parks. If you’re ever looking to live off the land in New York City, you’d be hard-pressed to find a more suitable spot to pitch a tent.

A local man goes crab hunting.

The sun sets on a creek at the north side of Gravesend’s secret park.

Beyond NYC: Ghost Hunting in the “Bloody Pit”

Imagine a picture-perfect October afternoon—white steeples set against a crisp blue sky, apples to be picked, pumpkins to be carved, colonial headstones moldering beneath a gaudy display of fall foliage…

Only in New England is the essence of autumn so vividly arrayed, no more so than the Berkshires of western Massachusetts. The pastoral region was revered among literary luminaries of the 19th century—it’s rumored that Melville first envisioned his white whale in the wintry outline of Mount Greylock—but it’s also a wellspring of inspiration for local storytellers. The Berkshire hills are laced with legends and more than their fair share of ghost stories, so I got out of town to explore this mysterious region and hopefully encounter a few ghosts, just in time for Halloween.

The Old Coot is usually sighted in January; so I settled for this reenactment.

My first stop was the Bellows Pipe Trail on Mount Greylock, known to be haunted by a ghost called the “Old Coot.” This unfortunate soul went by the name of William Saunders in life and earned his living as a farmer before being called away to fight for the Union in 1861. His wife Belle assumed the worst when the letters stopped coming after receiving word that her husband had been injured in battle. But Bill Saunders had survived, only to return home and find Belle remarried. He retreated to a ramshackle cabin on Mount Greylock, where he lived out the rest of his days as a hermit, occasionally working on nearby farms. One day, a group of hunters entered his shack and came across his lifeless body. They were the first to describe a sighting of the Old Coot’s spirit fleeing up the mountain, but he’s haunted the trail ever since.

Madame Sherri failed to make an appearance on her old staircase. (Click here for a less ghostly image)

Madame Sherri

On the outskirts of Brattleboro, rumors about one eccentric local are still raising eyebrows more than fifty years after her death. Madame Sherri was a well-known costume designer in jazz-age New York City whose designs were featured in some of the most successful theatrical productions of the day. After her husband died of “general paralysis due to insanity,” Madame Sherri retreated to an elaborate summer home in the Berkshires, where she was known to throw lavish and unsavory parties for her well-heeled guests, often gallivanting about town in nothing but a fur coat. Gradually, her fortune was depleted and the dwelling was abandoned in 1946. Late in life, she became a ward of the state and died penniless in a home for the aged. Her “castle” burned to the ground on October 18, 1962, but its dramatic granite staircase remains to this day. Sounds of revelry have been heard emanating from the ruins of the old estate, where the apparition of an extravagantly dressed woman has often been spotted ascending the staircase.

Parked at the base of Mount Greylock.

If Madame Sherri’s Forest and the Old Coot’s trail don’t give you goosebumps, this next one might. To get there, you have to go down—way down—into the Hoosic River Valley to the bedrock of the Hoosac Mountains in North Adams, MA. Turn off on an unnamed dirt road, park at the train tracks, take a short hike, and you’ll come face to face with one of the most haunted places in New England. How far would you be willing to venture into the “Bloody Pit?”

The town of North Adams appears from a hillside en route from Mt. Greylock.

In 1819, a route was proposed to transfer goods from Boston to the west, and the Hoosac Range was quickly identified as the project’s biggest obstacle. Construction began in 1855 on the 5-mile Hoosac Tunnel, but the dig was plagued with problems from the beginning. When steam-driven boring machines, hand drills, and gunpowder proved too slow, builders turned to new, untried methods, namely nitroglycerine, an extremely powerful and unstable explosive. The tunnel claimed close to 200 human lives over the course of its 20-year construction, earning the nickname “The Bloody Pit.” The work was merciless, but precise—when the two ends met in the middle, the alignment was off by only one half inch.

An abandoned pumphouse sits beside a waterfall in the woods near the railroad tracks.

On March 20, 1865, Ned Brinkman and Kelly Nash were buried alive when a foreman named Ringo Kelly accidentally set off a blast of dynamite. Fearing retaliation, Ringo disappeared, but one year later, he was found strangled at the site of the accident, two miles into the tunnel. No one witnessed the crime, but most men agreed—the ghosts of Ned and Kelly had slaked their revenge.

The entrance to the Hoosac Tunnel opens up from around a bend in the tracks.

The most costly accident in the tunnel’s history occurred the following year on October 17th, halfway through the digging of a 1,000-foot vertical aperture called the Central Shaft which was designed to relieve the buildup of exhaust in the tunnel. Thirteen men were working 538 feet deep when a naphtha lamp ignited the hoist building above them, sending flaming debris and sharpened drill bits raining down. The explosion destroyed the shaft’s pumping system and the pit soon started filling up with water. When workers recovered the bodies several months later, they discovered that several of the men had survived long enough to construct a raft in a desperate attempt to escape the rising waters. The accident halted construction for the better part of a year.

The entrance to the Hoosac Tunnel

When work resumed, laborers reported hearing a man’s voice cry out in agony, and many walked off the job, claiming the tunnel was cursed. Through the 19th century, local newspapers reported headless blue apparitions, ghostly workmen that left no footprints in the snow, and disappearing hunters in and around the Bloody Pit. As recently as 1974, a man who set out to walk the length of the tunnel was never heard from again.

Staring down the black maw of the Hoosac Tunnel.

In spite of these tales, I found myself standing at the entrance to the West Portal, where a single bat sprung out of the darkness, setting the tone for what would prove to be a rather unsettling experience. The tunnel is undeniably creepy, lined with old crumbling bricks, half flooded with gray water, and coated with almost two centuries of soot and grime. It didn’t help that I was visiting on October 17th, the anniversary of its grisliest accident…

Sure enough, the moment I stepped across the threshold, my camera started taking pictures by itself. (Granted, it’s been having issues lately, but the timing and severity was uncanny.) The whole time I was in the tunnel, I was unable to gain control of the shutter, and had to resort to setting up a shot and waiting for the “unseen forces” to take each picture. It beats me why a ghost would choose to fiddle with my camera rather than, say, making the walls bleed, but the entire encounter left this skeptic scratching his head. Were these the spirits of the Hoosac Tunnel?

* * *

Back at the campsite, with the fire extinguished, I settled in for a fitful sleep on the hard ground, unable to shake that uneasy feeling. That night, the falling leaves outside the tent sounded just like footsteps. When the wind blew, the whole forest sounded like a crowd of ghosts walking. It was exactly the kind of night I had hoped to pass in the Berkshire hills, a chance to experience the other side of the season, beyond the spiced cider and the pumpkin lattes, far older than the covered bridges that cross the languid Hoosic River, that ancient date that marks the beginning of the dark half of the year, when the boundary between the living and the dead is at its thinnest point.

As far as I dared to go in the haunted Hoosac Tunnel.

A bit of Halloween spirit displayed outside the Bellows Pipe Trail.

The Red Hook Grain Terminal

On foggy mornings, nothing can rival the Grain Terminal’s spectral allure.

It’s been nearly fifty years since a freighter docked at the Red Hook Grain Terminal; now black mold overspreads its concrete silos like a mourning veil.

Its origin can be traced to the turn-of-the-century construction of the New York State Barge Canal, which widened and rerouted the Erie Canal at great expense to facilitate the latest advances in shipping. By 1918, New York City was lagging behind in the nation’s grain trade, and the canal was failing, operating at only 10% of its capacity. A new facility was built in the Port of New York to invigorate the underused waterway—a state-run grain elevator in the bustling industrial waterfront of Red Hook, Brooklyn.

The structure is largely composed of 54 circular silos with a combined capacity of two million bushels. Grain was mechanically hoisted from the holds of ships, elevated to the top of the terminal, and dropped into vertical storage bins through a series of moveable spouts. When a purchase was made, the force of gravity would release the grain from the bins, at which point it was elevated back to the top of the terminal and conveyed to outgoing ships.

A shallow puddle makes an effective reflecting pool after a downpour, in keeping with the monumental atmosphere of the place.

Packed with rows of white columns, the ground floor resembles an ancient house of worship.

Red Hook’s grain elevator is one of many similar structures built across the country in the 1920s, most notably in Buffalo, NY. Guided by practical concerns and the laws of nature, American engineers had arrived at a new style of architecture, making a lasting impression on European architects. In Toward an Architecture (1928), Le Corbusier called the American elevators “the first fruits of a new age.” Their influence can be traced through the Brutalist movement of the 50s and 60s, through which inexpensive, unadorned cement structures dominated post-war reconstruction in Europe.

The Grain Elevator was an engineering marvel, but never became a commercial success. The structure quickly became obsolete in the mid-20th century as grain trade in the Port of New York steadily declined from 90 million bushels a year in the 1930s to less than 2 million in the 1960s. Contractors grew to avoid the New York Harbor, where the cost of unloading grain came to three to four times the rate of competing ports in Baltimore, Philadelphia, and New Orleans, largely due to local union restrictions.

The Grain Terminal was emptied of its last bushel in 1965.

The collapse of the grain trade made up a small part of an overall decline along Red Hook’s industrial waterfront in the second half of the 20th century as shipping methods evolved and moved elsewhere. When the jobs dried up, much of the area cleared out, leaving a slew of vacant warehouses and decaying docks. In the year 2000, most of Red Hook’s 10,000 residents lived in the Red Hook Houses, one of the city’s first public housing projects. The development was a notorious hotbed for crack cocaine in the 80s and early 90s, but conditions have gradually improved over the years. A near complete lack of major subways and buses stalled gentrification in the neighborhood, but signs are becoming more common. Today, Van Brunt Street is scattered with specialty wine bars, cupcake shops, and craft breweries, and a big box IKEA store opened in 2007 on the site of a former graving dock.

The Grain Terminal has been the subject of a number of reuse proposals over the years, but none of the plans have amounted to real progress at the site. The building sits on the grounds of the Gowanus Industrial Park, which currently houses a container terminal and a bus depot, among other industrial tenants. The owner is now seeking approval for a controversial plan to extend his property into the bay with landfill, using a concoction of concrete and toxic sludge dredged from the floor of the Gowanus Canal.

As battles wage over the future of the property, the Red Hook Grain Terminal hovers over the Henry Street Basin like a grieving ghost on a widow’s walk, watching for ships that will never return…

A word to the wise: the grounds of the Grain Terminal are patrolled by security, and they’re cracking down on trespassers.

Moveable spouts delivered grain to individual silos.

A 90-foot staircase of corroded metal slats connects the first floor to the top of the storage bins.

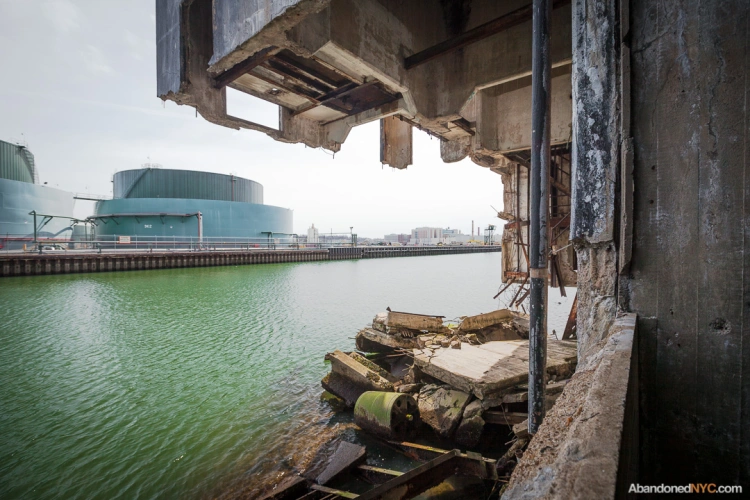

The lower levels of two out of three staircases have collapsed into the basin…

Whole sections of the building are on their last legs…

..crumbling into the canal like a latter-day House of Usher.

The building is topped by a small tower on the north end…

…and a larger structure to the south.

The top floor is strewn with manhole-sized apertures, which give way to the mind-numbing vacuum of the empty grain silos.

Looking down these is like staring into the face of death.

It’s a looooong way down.

Ruins of the ’64 New York World’s Fair

The empty observation towers of the New York Pavilion hover over Flushing Meadows-Corona Park.

In Flushing Meadows-Corona Park, the oddball ruins of the “Tent of Tomorrow” are fading into yesterday. This land had been home to the Corona Ash Dumps—immortalized as the “valley of ashes” in the Great Gatsby—until master builder Robert Moses set out to transform the area by selecting it as the site of the 1939 New York World’s Fair. While the overall design of the park was laid out for the ’39 event, its most evident landmarks date back to the ’64 exhibition. The Space Age design of the New York Pavilion was intended to inspire visitors with the promise of the future, but today it serves to firmly plant the structure in the context of the 1960s.

The New York State Pavilion in its youth.

The tallest tower was the highest point in the fair at 226 feet.

Concieved by New York businessmen and funded by private financing, the 1964-65 New York World’s Fair was once again headed by Robert Moses, who saw the project as an opportunity to complete his vision for Flushing Meadows Park. In order to make the fair financially feasible, organizers charged rent to exhibitors and ran the attraction for two years, ignoring the regulations of the worldwide authority on world’s fairs (the Bureau of International Expositions.) As a result, the BIE refused to sanction the fair and instructed its forty member nations not to participate, which included Canada, most European Nations, Australia, and the Soviet Union.

Faint remnants of bright yellow paint can still be spotted on the metal components of the structure.

The fair was dedicated to “Man’s Achievement on a Shrinking Globe in an Expanding Universe,” but the majority of exhibitors were American companies. Some of the most popular destinations included General Motors’ “Futurama” exhibit, Disney’s original “It’s A Small World” attraction, and a model panorama of New York City (which you can still visit at the Queens Museum of Art). Although over 51 million people attended the fair, the turnout was far less than expected. The project ended in financial failure, returning only 20 cents on the dollar to bond investors.

The observation decks were re-imagined as space ships in the original Men In Black film.

Most of the World’s Fair pavilions were temporary constructions that were demolished within six months of closing, but a few were deemed worthy of becoming permanent fixtures of the park. Once the centerpiece of the fair, the 12-story high stainless steel Unisphere has gone on to become a widely recognized symbol of Queens. Designed by notable modernist architect Philip Johnson, the nearby observation towers and the “Tent of Tomorrow” remain striking examples of the Space Age architecture the fair embraced. Unfortunately, they’ve sat empty for decades, and are starting to show their age. In the Tent of Tomorrow, space that once hosted live concerts and exciting demonstrations are occupied by stray cats and unsettling numbers of raccoons.

The Tent of Tomorrow once held the record as the largest cable suspension roof in the world.

The pavilion was reopened as the “Roller Round Skating Rink” in 1970, but roof tiles soon became unstable and the city ordered the attraction to close by 1974. Owing to their singular design, the structures have found their way into the background of many feature films, television shows, and music videos, including a memorable turn as a location and plot element for the original Men in Black. You can still make out the design of the pavilion’s main floor—modeled after a New York state highway map—in this late ’80s They Might Be Giants video.

The New York State Pavilion was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 2009, and a group of preservationists have helped clean up the exterior, restoring a bit of the original color scheme. As we near the 50th anniversary of the ’64 World’s Fair, here’s hoping something can be done to put these unique structures back to use.

A group of preservationists have restored the original paint job on the structure’s exterior.

Vines, and a not entirely incongruous robot head, have been affixed to this tower.

San Francisco’s Spooky Sutro Baths

Crumbling stairways at San Francisco’s Sutro Baths.

When the Sutro Baths first opened to the public in 1896, the west side of San Francisco was a vast region of all-but-unpopulated sand dunes. The sprawling natatorium was a pet project of Adolph Sutro, a wealthy entrepreneur and former mayor of San Francisco who became widely known as a populist over his illustrious career. Before constructing his magnificent bathhouse at Land’s End, he opened the grounds of his personal estate to all San Franciscans. Later, when transportation costs proved too high for many to reach his baths, he built a new railroad with a lower fare.

The Sutro Baths were the world’s largest indoor swimming establishment, with seven pools complete with high dives, slides, and trapezes, including one fresh water pond and 6 saltwater baths of varying temperatures with a combined capacity of 10,000 visitors. The water was sourced directly from the Pacific Ocean during high tide, and pumped during low tide at a rate of 6,000 gallons per minute. The monumental development also featured a 6,000-seat concert hall and a museum of curios from Sutro’s international travels.

The Sutro Baths in their glory days.

What remains of the Baths today.

The Baths’ popularity declined with the Great Depression and the facility was converted to an ice skating rink in an attempt to attract a new generation of visitors. Facing enormous maintenance costs, the Sutro Baths closed in the 1960s as plans were put in place for a residential development on the site. Soon after demolition began, a catastrophic fire broke out, bringing what remained of the glass-encased bathhouse to the ground. (There’s some suspicion that the fire was related to a hefty insurance policy on the structure, though it’s never been confirmed.)

The condo plans were scrapped and the concrete footprints of the Sutro Baths were left largely undisturbed. In 1973, the site was included in the Golden Gate National Recreation Area, and the ruins were opened to the public for exploration. This is not your typical park; as one sign warns, “people have been swept from the rocks and drowned.”

The highlight of any trip to the Sutro Baths is the cliffside tunnel. Through a pair of apertures, visitors can watch waves collide on the rocks below as the unlit corridor fills with briny mist and the booming sounds of the sea. In this spot, you might catch yourself believing vague rumors of hauntings that hang like a fog around the ruins of the Sutro Baths, or as some would have it, strange sightings of Lovecraftian demigods that lurk in its network of subterranean passages…

-Will Ellis

The cavern at Sutro Baths.

A misty opening reveals the teeming ocean below.

A portion of the property has been deemed too dangerous for the public…

…apparently for good reason.

This pool was freshly inundated with sea water.

Stunning views of the foggy Pacific from a clifftop lookout.

Purple flowers color an otherwise gloomy scene.

Green Thumbing Through the Boyce Thompson Institute

The abandoned Boyce Thompson Institute in Yonkers.

In 1925, Dr. William Crocker spoke eloquently on the nature of botany: “The dependence of man upon plants is intimate and many sided. No science is more fundamental to life and more immediately and multifariously practical than plant science. We have here around us enough unsolved riddles to tax the best scientific genius for centuries to come.”

As the director of the Boyce Thompson Institute in Yonkers, Crocker was charged with leading teams of botanists, chemists, protozoologists, and entomologists in tackling the greatest mysteries of the botanical world, focusing on cures for plant diseases and tactics to increase agricultural yields. The facility was opened in 1924 as the most well equipped botanical laboratory in the world, with a system of eight greenhouses and indoor facilities for “nature faking”—growing plants in artificial conditions with precise control over light, temperature, humidity, and carbon dioxide levels.

The sun sets on the greenhouses of the Boyce Thompson Institute.

The institution had been founded by Col. William Boyce Thompson, a wealthy mining mogul who became interested in the study of plants after witnessing starvation while being stationed in Russia, (although an alternate history claims he just loved his garden.) Recognizing the rapid rate of population growth worldwide, he sought to establish a research facility with an eye toward increasing the world’s food supply, “to study why and how plants grow, why they languish or thrive, how their diseases may be conquered and how their development may be stimulated.”

By 1974, the Institute had gained an international reputation for its contributions to plant research, but was beginning to set its sights on a new building. The location had originally been chosen due to its close proximity to Col. Thompson’s 67-room mansion Alder Manor, but property values had risen sharply as the area became widely developed. Soaring air pollution in Yonkers enabled several important experiments at the institute, but hindered most. With a dwindling endowment, the BTI moved to a new location at Cornell University in Ithaca, and continues to dedicate itself to quality research in plant science.

Most of the interiors had a near-complete lack of architectural ornament, but the entryway was built to impress.

The city purchased the property in 1999 hoping to establish an alternative school, but ended up putting the site on the market instead. A developer attempted to buy it in 2005 with plans to knock down the historic structures and build a wellness center, prompting a landmarking effort that was eventually shot down by the city council. The developer ultimately backed out, and the buildings were once again allowed to decay. Last November, the City of Yonkers issued a request for proposals for the site, favoring adaptive reuse of the existing facilities. Paperwork is due in January.

Until then, the grounds achieve a kind of poetic symmetry in warmer months, when wild vegetation consumes the empty greenhouses, encroaching on the ruins of this venerable botanical institute…

-Will Ellis

Ornate balusters made this staircase the most attractive area of the laboratory.

A central oculus leads to this mysterious pen in the attic.

This stone sphere had been the centerpiece of the back facade, until someone decided to push it down this staircase. See its original location here.

The city gave up on keeping the place secured long ago.

The north wing had been gutted at some point.

An interesting phenomenon in the basement–a population of feral cats had stockpiled decades worth of food containers left by well-meaning cat lovers.

A view from the upstairs landing was mostly pastoral 75 years ago.

The main building connects to a network of intricate greenhouses.

The interiors were covered with shattered glass, but still enchanting.

A Baseball Graveyard in Queens

An overgrown overpass at Union Turnpike and Woodhaven Boulevard, part of the proposed Queensway project.

Abandoned for half a century, the old Rockaway Beach Branch of the Long Island Railroad is stirring debate today as opposing visions for its future emerge. Before it’s reactivated to serve beleaguered Queens commuters, or converted to the Queensway, (a linear park similar to Manhattan’s High Line), the track remains a 3.5 mile wilderness, with more than a few secrets scattered among the ruins.

At the northern edge of Forest Park, the rails terminate in a parking lot, where antiquated electrical towers have been adapted as streetlights. Across the Union Turnpike, there’s a plot of land that may be the most obscure section of the Rockaway Branch, a triangular junction wedged between a dilapidated warehouse and a complex of baseball diamonds. A well-trod path leading into the place quickly dissolves into a tangle of branches; the plant life is especially lush here, and difficult to navigate.

…just a few paces from a chain link fence that separates a packed field of cheering little leaguers.

Standing in the shadows just beyond the diamond’s edge, you’re practically invisible, in a world between worlds, and right at your feet, dozens of baseballs bloom from the earth like mushrooms…

This is the place the balls go where you can’t get them back, each a martyr and a monument to a home run that may have taken place decades ago or just this morning. Stripped of their leather casing, the older specimens reveal a second skin of frayed cotton yarn. The most ancient are unrecognizable, corrupted to a truffle-like core of black, scabrous rubber. Together, they linger in a bizarre kind of afterlife, populating the century-old tracks of a forgotten railroad—when a place is left alone, the past piles up.

Check out the gallery below for an education in baseball construction, and decay…

-Will Ellis

Ghosts of the West Side Highway

New York City isn’t known for its roadside attractions or its motor inns, but along the West Side Highway, you can still find shades of the open road. What could be more emblematic of the highway state of mind than the diner, whose very contours suggest forward motion, gleaming like hubcaps across the American landscape? Abandoned between auto repair shops and a gentlemen’s club, the diner at 357 West Street fully commits to the mystery and isolation only hinted at in Edward Hopper’s Nighthawks, (which was based on a nearby diner in Greenwich Village.) Today, the only travelers this diner entertains are pedestrians who can’t resist taking a peek inside…

The restaurant closed in 2006 after 50 years of operation, having gone through a steady succession of owners and names, including the Terminal Diner, the Lunchbox Diner, Rib, and perhaps most fittingly, the Lost Diner. Constructed by the New Jersey-based Kullman Diner Car Company, the structure is typical of the Art-Deco diner cars manufactured in the 40s and 50s, which have since become an iconic fixture of cities across America. Most of Manhattan’s once numerous diners have been demolished or moved in recent years; you can still visit Soho’s famous Moondance Diner—in Wyoming. The steep decline in the condition of the Lost Diner limits its chance of being relocated.

Throughout the space, a steady rush of traffic fills the air in the absence of clinking silverware. Sunlight bounced from a passing windshield momentarily dazzles an aluminum ceiling. In the dining room, shattered glass joins a host of reflective surfaces, causing the room to glimmer with points of light in the evening. In the past year, the windows of the diner have been knocked out and the interior has been ravaged. Old mattresses, fresh garbage, and a homemade toilet point to a recent, if not ongoing habitation. Stacks of rotting food cartons fill an overturned refrigerator, covered with the husks of long-dead pests. In the former kitchen, a dry erase board lists celery seed, walnut oil, and Windex for a shopping trip that was doomed to be this diner’s last.

Down the road, the abandoned Keller Hotel makes a perfect counterpart to the Lost Diner, another vacant holdout in a neighborhood that’s quickly being overcome by luxury developments. The six story hotel was completed in 1898 as a lodging for travelers arriving from nearby ferries and cruise ships. By the 1930s, the area had become one of the most active sections of the port of New York, and the building became a flophouse for sailors. Later, the club downstairs catered to New York’s gay community as the oldest “leather bar” in the West Village. The Keller Hotel was landmarked in 2007, but has stood unoccupied for decades. When and if the building is renovated, here’s hoping the slightly sinister “HOTEL” sign will be saved.

Checking in to Grossinger’s Resort

The ransacked Paul G. hotel, showing the hallmarks of a recent paintball game.

Past a deserted security desk, waist-high grasses choke back the yawning entrance to the Jennie G. Hotel, whose toppled fence serves more as an invitation than a barrier. Here in the sleepy town of Liberty, NY, this derelict hilltop lodge is not only a destination for the curious, it’s a daily reminder of the town’s old eminence, an emblem of a dead industry, visible from miles around.

In its time, Grossinger’s Catskills Resort was a fantasy realized, where wealthy businessmen, celebrity entertainers, and star athletes gathered to mingle with those that they liked and were like, to see and be seen, and to enjoy, rightly so, the things they enjoyed. As the slogan goes—Grossinger’s has Everything for the Kind of Person who Likes to Come to Grossinger’s.

Flowers left by a former guest, or a prop from an old photo shoot.

If you’re the kind of person that’s inclined to spend their vacation somewhere dark, dusty, and dangerous, the motto still rings true today, and you’re not coming for the five-star kosher kitchen. For just as quickly as the resort prospered into a world-class institution, it’s descended into a swift decay. Explorers frequent the grounds, armed with cameras in an attempt to capture the beauty in its devastation, sifting through the artifacts—a broken lounge chair, old reservation records—piecing together a lost age of tourism.

A generation ago, this region of the Catskills was known as the Borscht Belt, a tongue-in-cheek designation for a string of hotels and resorts that catered to a predominantly Jewish customer base in a time when discrimination against Jews at mainstream resorts was widespread. In popular culture, the most notable representation of this time and place is Dirty Dancing, which was supposedly inspired by a summer at Grossinger’s. The unexpected success of its film adaptation had little effect on the long-struggling resort—in 1986, a year before the film was released, Grossinger’s ended its 70 year legacy.

The story of Grossinger’s is, at its root, an American story. The Grossingers were Austrian immigrants, who after some early years of struggle in New York City, and a failed farming venture, opened a small farmhouse to boarders in 1914, without plumbing or electricity. They quickly gained a reputation for their exceptional hospitality and incredible kosher cooking and outgrew the ramshackle farmhouse, purchasing the property that the resort still occupies today.

Grossinger’s rise to prominence is largely attributed to the couple’s daughter Jennie, who worked there as a hostess in its early years. Later, Jennie’s legendary leadership would transform the resort from its humble beginnings to a massive 35-building complex (with its own zip code and airstrip), attracting over 150,000 guests a year, and establishing a new type of travel destination that renounced the quiet charms of country living for a fast-paced, action-packed social experience that met the expectations of its sophisticated New York clientele.

Remnants of an attempt to burn down the Jennie G.

Every sport of leisure had its own arena, with state of the art facilities for handball, tennis, skiing, ice skating, barrel jumping, and tobogganing, along with a championship golf course. In 1952, the resort earned a place in history by being the first to use artificial snow. Its famous training establishment for boxers hosted seven world champions. Its stages launched the careers of countless well-known singers and comedians. In its day spas and beauty salons, ballrooms and auditoriums, guests were offered a level of luxury that even the wealthiest individuals couldn’t enjoy at home, earning Grossinger’s the nickname, “Waldorf in the Catskills.”

A daily missive called The Tattler identified notable guests and the business that made their respective fortunes. Weekly tabloids published on the grounds boasted the presence of celebrity athletes and entertainers. But for all the emphasis on earthly pleasures and material wealth, Jennie G. ensured that the Grossinger’s experience was warm and personal, always treating guests like one of the family, even when visitors reached well over 1,000 per week.

By the late sixties, the Grossinger’s model had started to fall out of favor as cheap air travel to tourist destinations around the world became readily available to a new generation. After the property was abandoned, several renovation attempts were aborted by a string of investors. Widespread demolition has greatly diminished the sprawl of the original resort, but several of the largest buildings remain. Most have been stripped of any vestige of opulence, and some structures are barely standing; no more so than the former Joy Cottage, whose floors might not withstand the footfalls of a field mouse.

Artifacts from the hotel’s glory days are few and far between, but Grossinger’s most recent batch of visitors has been quick to leave its mark. In a haunting hotel filled with empty rooms, some scenes are startlingly arranged, with collected mementos photogenically poised in the pursuit of a compelling shot. Despite these attempts to prettify Grossinger’s decline, the grounds retain an air of savage dilapidation, and an utter submission to nature.

An indoor swimming pool is Grossinger’s most enduring spectacle, and has become a favorite location of urban explorers near and far. Radiance remains in its terra-cotta tiles and its well-preserved space age light fixtures. Its dimensions continue to impress, as do the postcard views through its towering glass walls, all miraculously intact. It’s growth, not decay, that makes this pool so picturesque—the years have transformed this neglected natatorium into a flourishing greenhouse. Ferns prosper from a moss-caked poolside, unhindered by the tread of carefree vacationers, urged by a ceiling that constantly drips. Year-round scents of summer have bowed to a kind of perpetual spring, with the reek of chlorine and suntan lotion replaced by the heady odor of moss and mildew—it’s dank, green, and vibrantly alive.

Meanwhile, areas across the region that once relied on a thriving tourism industry have fallen into depression or emptied out. The Catskills is attempting to rebrand, updating its image and holding online contests to determine a new slogan. The winner? The Catskills, Always in Season.

Though it remains to be seen whether the coming seasons will bring new visitors, there’s no doubt they’re serving to erase the region’s outmoded reputation. With each passing year, in ruined hotels across the Catskills, the physical remnants of lost vacations dwindle. Indoors, snowdrifts weigh on aching floors; leaf litter collects to harbor the damp or fuel the fire. Vines claim what the rain leaves behind, compelling the constant progress of decay. Scattered in photo albums, hidden in bottom drawers, excerpted from yellowing newsprint, the memories will follow, clearing the way for new journeys. Before it’s forgotten, here’s one more look inside the celebrated resort.

This catwalk ensured a comfortable commute from your suite at the Paul G. to the indoor pool year-round.

A pitch-black beauty salon lit with the aid of a flashlight.

The ruined entrance to the hotel spa.

Office on the bottom floor of the Jennie G. Hotel.

The best preserved room, with two murphy beds, and a carpet of moss.

In most rooms, peeling wallpaper was all that remained.

The ground floor of the management office, now on the verge of collapse.

Hotel records neatly arranged on a mattress, by a photographer, no doubt.